In May, residents of 577 apartments in Barrington Plaza, an imposing complex of three towers near the UCLA campus, received eviction notices. It would be the largest eviction from rent-controlled housing in Los Angeles in at least four decades.

When the evictions were announced, Barrington Plaza’s owner, Douglas Emmett Inc., said in a news release that was part of a Securities and Exchange Commission filing that residents needed to move out in order for it to make fire safety upgrades required by the city of Los Angeles. There have been two fires at the complex, in 2013 and 2020. After the 2020 fire, the city declared eight of the floors of one of the towers unfit for occupancy.

The owner said the city made its approval of a permit to restore the fire-damaged floors contingent “upon the installation of sprinklers and other life safety equipment.” The safety improvements, including installing sprinklers, “cannot be accomplished without vacating all three towers,” the company news release said. The work “can take several years at a cost of over $300 million,” the news release added.

The company continued to cite the city requirements as the reason for the evictions to the City Council and its investors, and news stories reported it as a fact.

But a city spokesperson said there are no such requirements. When contacted by Capital & Main, the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety said it has not mandated the work the building owner said was required. “No enhancements were requested or required by LADBS,” Department of Building and Safety spokesperson Gail Gaddi said in an email response to questions.

The city requires the installation of fire sprinklers in residential towers built after 1974, but Barrington Plaza was completed in 1961, well before then. “The building’s age pre-dates required sprinkler installation,” Gaddi said.

If the fire safety renovations are not in fact required, the company has misinformed the public about the reason for the mass eviction. Larry Gross, executive director of the Coalition for Economic Survival, an organization supporting the tenants in a lawsuit to block the evictions, said the revelation that the city disputes the company’s claims “will hopefully give more of our elected officials, city council and city attorney the courage to speak out and denounce Douglas Emmett for these clearly unjust evictions.”

The company maintains that its costly fire safety upgrades are required by the city. “We stand by all previous comments and all filings with the SEC,” spokesperson Eric Rose told Capital & Main in an email.

Tenants and their advocates said the evictions are part of a strategy to pave the way for a high-end apartment complex that can command significantly higher rents.

When asked directly about the city’s statement that no fire safety work is required because of the age of the building, Rose declined to provide evidence of those requirements, citing pending litigation.

Barrington Plaza’s owner filed a lawsuit against its insurers in early October in which it argued that the L.A. Department of Building and Safety issued “a directive that Barrington include a code-compliant sprinkler system in all three towers at Barrington Plaza.” The lawsuit also noted that the Los Angeles Fire Department “advised Barrington that it must install fire sprinklers at Barrington Plaza.” Fire department officials did not respond to requests for comment.

In the lawsuit, filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court, Barrington Pacific LLC, the Douglas Emmett subsidiary that owns the complex, claimed that more than a dozen of its insurance companies pressured the city to drop safety requirements for the repair work in order to avoid a substantial payout. The suit claims the insurance companies contacted fire and building officials “on multiple occasions in recent months in an effort to convince them to retract or soften their directives relating to the installation of a sprinkler system at Barrington Plaza.”

Tenants and their advocates said the evictions are part of a strategy to pave the way for a high-end apartment complex that can command significantly higher rents.

“This is going to be premiere property on the Westside, three state of the art high-rises with all the amenities,” said Robert Lawrence, a Barrington Plaza tenant who faces a May 2024 move-out date. “They’re going to charge, you know, double or triple the rents.” Lawrence currently pays $2,400 per month for his one-bedroom apartment.

The planning department approved the exterior remodeling plans with little fanfare on May 11, a few days after the eviction notices were served to the tenants.

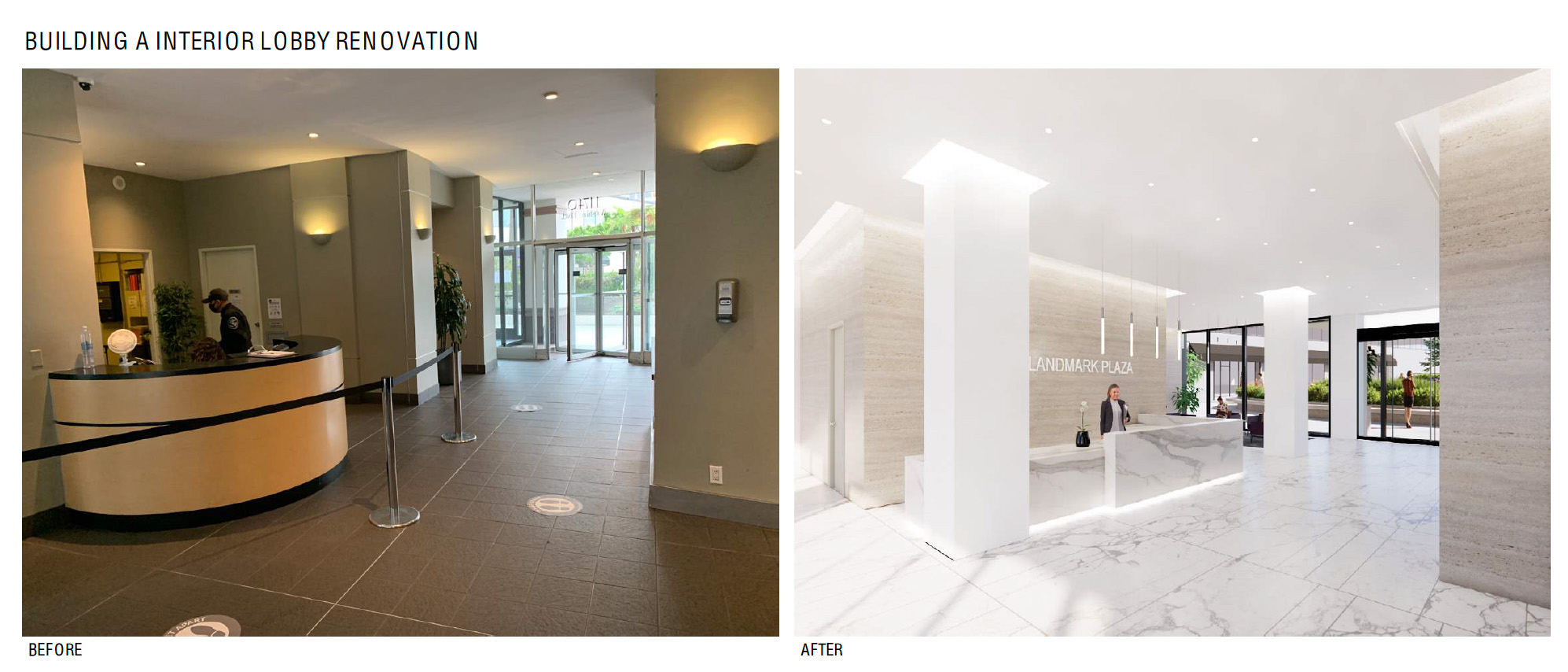

Those plans include new amenities such as balconies, lush landscaped gardens, glazed windows, a state-of-the-art gym, updated storefronts and a refurbished pool area complete with cabanas. The proposed new name, “Landmark Plaza,” aligns Barrington Plaza with its more luxurious neighbor, a Douglas Emmett tower called “The Landmark.” That 34-story apartment building leases 607-square-foot studio apartments for monthly rents ranging between $3,800 and $5,000.

In May, Douglas Emmett invoked the Ellis Act, which allows landlords to evict rent-controlled tenants if their apartments will no longer be used as rental housing. Owners can in the future return those units to the rental market, under certain conditions and sometimes penalties.

The company said on its Ellis Act application that it is undecided as to the property’s future use. “At this time, the owners of Barrington Plaza are removing the units from the market and have options as to how those units will change, be rehabilitated through new life safety measures or become something different,” Rose said in an email. He would not say what those options were. Most tenants left in September, but 170 tenants who are at least 62 years old or have a disability have until May 8, 2024, to depart.

“I’ve just never heard of such a thing that they have to evacuate all three buildings. It’s not part of what we do.”~ Todd Golden, Sprinkler Fitters U.A. Local Union 709

Tenants filed a lawsuit against Douglas Emmett in Los Angeles County Superior Court in May to block the initial evictions, which began in early September. The judge denied a request for a preliminary injunction as the lawsuit makes its way through the court. The dispute with tenants centers on conflicting interpretations of the Ellis Act. The tenants argue that the 1985 state law is designed for landlords who intend to permanently remove apartments from the rental market. Douglas Emmett, meanwhile, asserts that the Ellis Act does not address the landlord’s intentions, and that the years-long building renovation justifies its use. There has been little attention paid to Douglas Emmett’s widely publicized claim that city mandates prompted the landlord to invoke the law in the first place.

In fact, the insurance companies’ intervention in the Barrington Plaza’s permitting process is long-standing. Back in August 2020, an engineering firm acting on their behalf submitted a report to building officials arguing that the three towers should not fall under the city’s fire sprinkler law, according to a Capital & Main review of the Department of Building and Safety’s internal emails.

In June 2022, Joe Vo, a structural engineering assistant at the department, concurred with their conclusions, writing to an engineer at the firm, “under my permit review, I will not be asking for fire sprinklers” unless the building will be used as a gathering place for large numbers of people.

Fire safety experts supported installing fire sprinklers in the towers. In the 2020 fire, the second in seven years, 13 people were injured, and a college foreign exchange student died.

But some said that adding fire sprinklers to the buildings can be done at a lower cost and with less disruption than the approach planned for Barrington Plaza. “I’ve just never heard of such a thing that they have to evacuate all three buildings,” said Todd Golden, business manager for Sprinkler Fitters U.A. Local Union 709. “It’s not part of what we do,” he added. Even if the job is more disruptive, occupants can temporarily be housed in hotels or in a building’s empty apartments, said Golden, who is an experienced sprinkler installer and was invited by a tenant to tour the complex last summer.

Golden estimated the cost of installing fire sprinklers at $10 million for each tower, for a total of $30 million.

In 2021, there were 55 high-rise residential buildings built before 1974 that lack sprinklers in Los Angeles because the city does not mandate them.

Golden’s cost estimate is in line with that of Adel Salah-Eddine, now assistant chief in the Building and Safety Department’s Permit and Engineering Bureau. Eddine sought an estimate from an engineering firm for adding sprinklers and other fire safety upgrades to one of the three towers in 2021. The cost ranged from $3.5 million to $7.5 million, according to an internal department email.

But Emmett spokesperson Rose stressed that the fire safety job the company is undertaking at Barrington Plaza goes well beyond the installation of fire sprinklers, which is what is required under the city ordinance for newer buildings. Ceilings and stairwells will be rebuilt, walls demolished and replaced and utilities will be upgraded, he said. Smoke barriers will be installed around elevators, and the company will replace windows with fire-rated glass, he added.

Randy Roxson, a lawyer who serves as a consultant to the Sprinkler Fitters U.A. Local Union 709, has been advocating for a city ordinance that would require all pre-1974 high-rise apartment buildings to install sprinklers, a campaign that gained steam after the second Barrington Plaza fire. A former firefighter, Roxson applauds Douglas Emmett for undertaking the fire safety project. But he fears the widely publicized price tag and the prospect of mass evictions during a housing crisis could make city leaders shy about requiring sprinkler retrofits in older high-rise housing, he said.

Fran Campbell, an attorney who represents the Barrington Plaza Tenants Association, said tenants should be protected from eviction regardless of the scope of the fire safety work. She said that tenants covered by rent control should be housed under what’s known as a “tenant habitability plan,” which provides them temporary relocation during a disruptive renovation. “They’ve got to move people out and move them back in,” she said.

Housing advocates, meanwhile, worry that hundreds more units could be lost if landlords use the Barrington Plaza mass eviction as a playbook for how to empty rent-stabilized high-rise buildings to bring in higher-paying tenants. There are “similarly situated rent-controlled buildings that could be affected as this tactic is allowed to persist,” said Marissa Roy, a civil rights attorney who has been consulting with tenant advocates. In 2021, there were 55 high-rise residential buildings built before 1974 that still lack sprinklers because the city does not mandate them, according to the 2021 city report.

Tenants said they would be glad to live in a safer building, but they are not convinced that they should have to lose their homes as a result. About a dozen gathered around the pool on a recent day in October for coffee and pastries. The sun was bright, but many of the deck chairs were empty. Avy Jozay, who rents a one bedroom apartment for $1,800, has not found anything on the Westside to match what he has at Barrington Plaza on the Westside, where the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment is $3,053, according to Apartments.com. A phone repair technician, he’s currently unemployed. “I’m scared. I’m nervous,” he said.