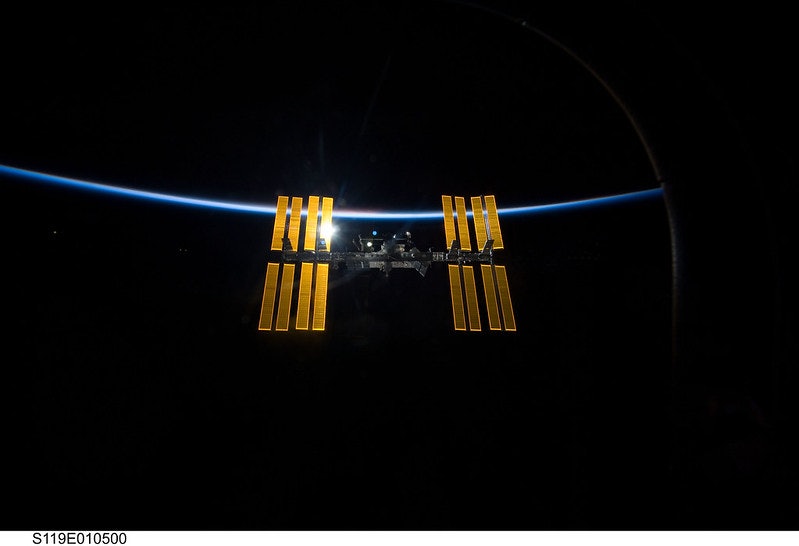

The International Space Station (ISS) has long been a place that has inspired some of the best of humanity. Over the past 23 years, the football field-sized space structure has represented a beacon of peace as well as the epitome of human exploration. But the ISS cannot last forever. Last year, NASA announced that the space laboratory would be decommissioned by the end of 2030, at which point the floating lab will crash into the ocean.

While the ISS was never meant to last forever — many a space exploration professional, and NASA, argue — what comes next is far less certain. What is certain is that there will be no next gen ISS. The next era of space stations will be owned by private companies, many of which are currently vying for contracts with NASA. But with these budding new stations, the space agency itself won’t be calling all the shots. They’ll be an anchor client, for sure, but a customer nonetheless. Finally, the crowning achievement of the ISS — it’s the largest peacetime international project ever, NASA astronaut Garrett Reisman tells Inverse — will fall to the wayside.

“It’s the most complex and largest engineering exercise we’ve ever accomplished as human beings. It’s also the largest international project, according to a variety of metrics, that’s been done in peace time,” Reisman says.

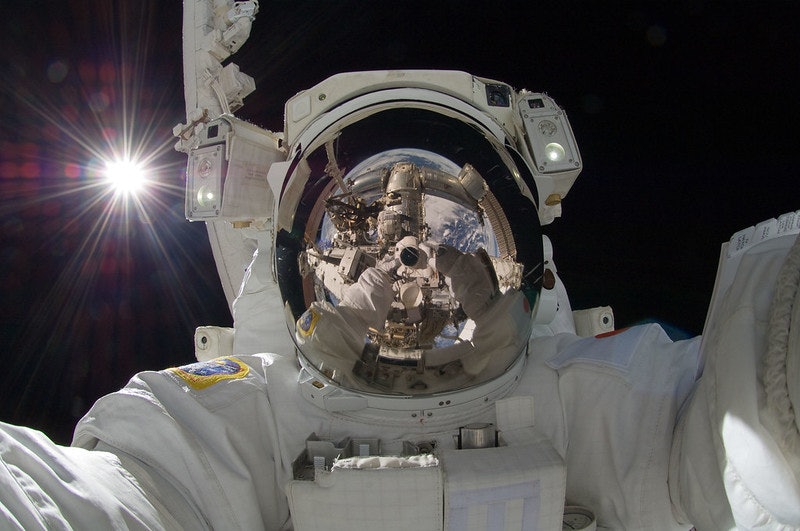

As we look to the future of space travel, what will be lost when the ISS is gone? A lot, many experts argue. The ISS is home to the longest-inhabited platform in space of all time. Continuous, non-stop occupation in space will be essential to getting humans to loftier destinations, like Mars. Astronauts like Frank Rubio and the Kelly twins have demonstrated the brink of human endurance in microgravity, and that’s barely scratching the surface about what we need to learn to venture farther away, Don Platt, associate professor of aerospace at the Florida Institute of Technology, tells Inverse.

What follows the ISS?

For NASA to split the costs of human space exploration in space, they’ll pay for access to these private space stations. Axiom, Blue Origin, Long Beach-based Vast Space, Nanoracks and Voyager Space are some of the companies striving to get the coveted NASA low-Earth orbit contracts through the agency’s Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations (CLD) program. NASA astronauts will then have to share the stations with other customers, either private citizens with a lot of disposable income to buy seats into space, or projects like Inspiration4 that sent an all-civilian crew to space, or astronauts from other space agencies or nationalities seeking to place one of their own some 250 miles high above Earth.

But to share the space practically, future stations must be much more automated. And smaller. They’ll need to be easier to maintain and use. All of this reduces their size.

The ISS is a massive collaboration of many space agencies around the world. NASA and Roscosmos lead the pack. But Japan, Europe, Canada and others have greatly contributed by way of modules, robotic arms, experiments and astronauts. The ISS is possible because there are control centers across the world, employing hundreds of people, to keep tabs on the gigantic craft. There’s no company that could hope to match this scale, Reisman says.

Bringing down the ISS

When it comes time to say goodbye, the ISS may require two years to fully be brought down.

The Space Shuttle, now retired, and its massive cargo space was essential to carrying segments of the ISS up to space. It’s unclear if the SpaceX Starship, currently in testing, will be ready in time for the ISS retirement procedures.

Reisman is thrilled by the progress and pace of development. Reisman was on the advisory board with Vast Space for about a year, and worked with SpaceX for seven years as its Falcon 9 rocket and Crew Dragon capsule were getting ready to carry their first humans to space. Reisman was too young to be a part of Apollo, but thinks perhaps the pace of current low-Earth orbit technological development offers a taste of what that iconic chapter in history must have been like.

But the ISS, Reisman’s home for a little more than three months over the course of two Space Shuttle missions in 2008 and 2010, embodies something unique. He says it was a more peaceful time, and its cultural role and its place in history as an incredible logistical accomplishment, may never happen again. He says we’ve moved away from that charmed period.

“There won’t be a government to government partnership. It won’t be the head of Roscosmos meeting regularly with the head of NASA, and the head of ESA and JAXA. That element won’t exist. I think that’s a shame. The ISS in its peak was really this beacon of hope. This Star Trek future, where we all get along,” Reisman says.