he Morgan Library & Museum owns part of an original sketch of Beethoven’s Hammerklavier piano sonata. In the margin, British publisher Vincent Novello writes that the document was given to him by “Mrs Streiker” – “one of Beethoven’s oldest and most sincere friends.”

Nannette Streicher’s marginalised place in history is encapsulated in these scribbled lines. While she was indeed one of the closest friends of Beethoven, whose 250th birthday will be celebrated in December, she was also one of the finest piano builders in Europe. She owned her own company – employing her husband, Andreas Streicher, a pianist and teacher, to handle sales, bookkeeping and business correspondence. But many Beethoven scholars, perhaps finding it inconceivable that an 18th-century woman could build a piano, have turned Andreas into the manufacturer and Nannette into his shadowy helpmate.

Born in Augsburg, Germany, in 1769, Nannette was the sixth child of Johann Andreas Stein, a renowned manufacturer who developed an innovative piano action, improving on the mechanism that causes the hammers to strike the strings. It became known as the “Viennese action.”

At 8, Nannette played in front of Mozart, who criticised her posture and grimacing, but admitted that she had “genius.” Two years later, she had mastered many of her father’s building techniques, earning a reputation as a mechanical wunderkind.

After her father’s death in 1792, Nannette, then 23 and recently married, transported the pianos by raft and set up the business in Vienna. She partnered with her 16-year-old brother, Matthaus, changing the company’s name from JA Stein to Geschwister (siblings) Stein. It was a time of rapid developments in piano design. With concerts moving beyond aristocratic salons into larger halls, manufacturers were under pressure to produce heavier, more resonant instruments.

Beethoven, who had met Nannette in Augsburg years earlier, asked to borrow one of her pianos for a 1796 concert in Pressburg (now Bratislava). Writing to Andreas, Beethoven joked that it was too “good” for him, because he wanted the “freedom to create his own tone.” In a follow-up letter, he complained that the piano was still the least developed of all the instruments and that it sounded too much like a harp.

The elegant Stein piano, with its light touch and silvery tone, wasn’t ideally suited to Beethoven’s wild and forceful performance style. Taking an obvious swipe at the composer, Andreas wrote an essay describing an unnamed pianist as a brutal murderer at the keyboard, “bent on revenge.”

“Already the first chords will have been played with such violence that you wonder whether the player is deaf,” he wrote.

The comment was sadly prescient. Beethoven had just begun to notice a decline in his hearing, but had told no one. Though he would later need a louder instrument to compensate for his deafness, he was at this point mainly concerned with finding a piano that accommodated his dynamic extremes.

Nannette had already expanded her keyboards’ range from five octaves to six and a half, but she was slow to make other major alterations to her father’s original design. It was a stressful time. By 1802, she was the mother of two small children, and a 6-year-old son had recently died. She was also engaged in a dispute with her brother; the siblings eventually decided to dissolve the company and strike out separately.

Matthaus took an ad in a local newspaper positioning himself as the rightful heir to the Stein name. Nannette, unwilling to relinquish her own claim, established Streicher nee Stein. She faced stiff competition from local builders, such as Anton Walter, as well as French and English manufacturers. Beethoven had purchased a French Erard in 1803, but he never stopped pressuring the Streichers to keep pace with his increasingly ambitious compositions.

By 1809, Nannette had considerably reworked her father’s design, turning out some of the largest, loudest and sturdiest pianos in Vienna. With a warehouse that produced 50 to 65 grand pianos a year, the Streicher firm was considered by many to be the finest in the city.

Beethoven’s relationships with women had always been fraught. He fell in love with pretty aristocrats who would never marry a commoner

In 1812, the Streichers built a 300-seat concert hall adjacent to their showroom; it was decorated with busts of well-known pianists, including a life mask of Beethoven by the sculptor Franz Klein. Concerts there, which attracted the likes of Archduke Rudolf, Beethoven and Andreas’ piano students, became a hub of Vienna’s musical life.

Nannette added another job when, in August 1817, she agreed to manage Beethoven’s chaotic household. The composer was going through one of the many crises that marked his life. His hearing had worsened, and he was in a creative slump. Having wrested control of his young nephew from his sister-in-law, he needed to give the appearance that he was providing the boy a good home.

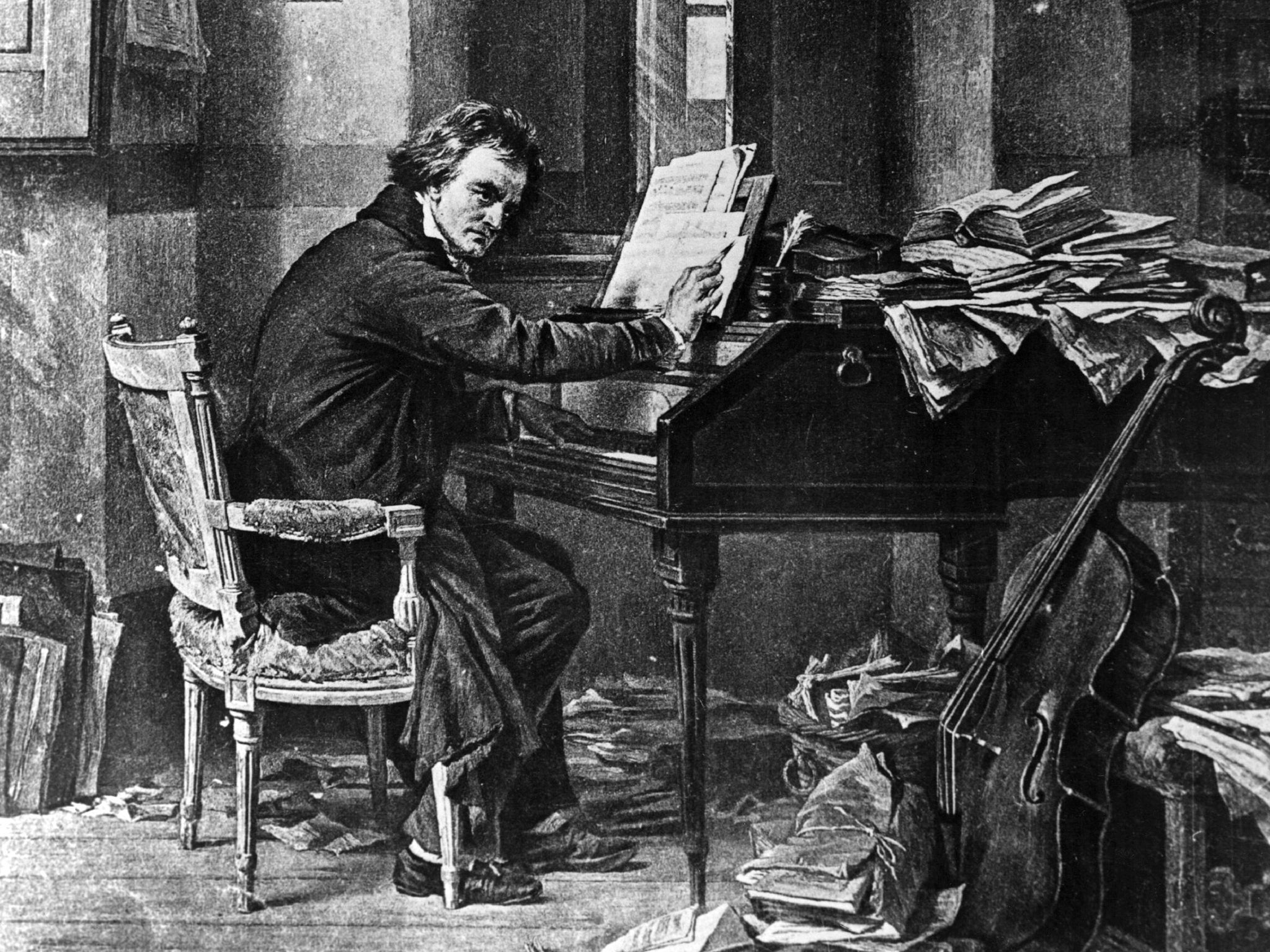

Over the next 18 months, Beethoven wrote Nannette over 60 letters, ordering her to take care of his laundry, mend his socks and buy groceries, dusters and shoe polish. Increasingly paranoid, he was convinced that the “beastly” servants were out to rob and poison him, and that they were colluding with his “immoral” sister-in-law.

Beethoven’s relationships with women had always been fraught. He fell in love with pretty aristocrats who would never marry a commoner, or else he developed filial attachments to married women. Nannette, with her plain, angular face and hawk-like eyes, wasn’t beautiful or highborn. But she was kind and generous; he called her his “good Samaritan”.

Beethoven’s relationship with her may have been his most successful with a woman. She wasn’t oblivious to his shortcomings, telling publisher Vincent Novello that he was “avaricious and always mistrustful”. But by that point, the pianist and piano builder had known each other for over two decades; they had a connection and were united in their devotion to the piano.

By assuming his household duties, Nannette cleared the way for Beethoven to write his most ambitious piano sonata, the colossal Hammerklavier. It was longer and more difficult than any of his other piano works, ending with a wild fugue. It ushered in some of his greatest works: the Missa Solemnis, Diabelli Variations and Ninth Symphony. Though he was now using an English Broadwood piano, he confided to Nannette in a letter that the post-1809 Streicher had always been his favourite.

Nannette outlived Beethoven by five years, dying in 1833, at 70. The Streicher firm continued to thrive under her son, Johann Baptiste, and then her grandson, Emil, who built pianos for Brahms. When Emil retired, in 1896, the company closed.

That would seem to have been the end of Nannette’s legacy. But her instruments live on in museums around the world and in the strong, nimble hands of women she inspired. In the mid-1960s, as Margaret Hood, an artist and calligrapher, raised two young children, she started making harpsichords. After doing research in Europe, she began specialising in reproductions of Streicher pianos, producing them in her Platteville, Wisconsin, workshop. She was building an 1816 Streicher six and a half-octave grand when she died in 2008.

Anne Acker, who trained as a concert pianist before studying mathematics and computer science, met Hood in Wisconsin. They bonded over their love of music, and Hood became Acker’s mentor. While caring for her children, Acker began building and repairing harpsichords and antique pianos, and after her friend’s death, she purchased the reproduction Streicher from Hood’s husband.

“I explained to him that a piano researched and begun by a woman, that is a replica of a piano designed and built by a woman, needs to be finished by a woman,” Acker said in an interview.

The piano – the work of three women over two centuries – had its debut at the Boston Early Music Festival in 2019. It was the year of Nannette’s 250th birthday.

© The New York Times