August 17, 2021 marks the 106th anniversary of the death of Leo Frank, a Jewish American living in Georgia who was lynched by an antisemitic mob after being convicted of murdering a 13-year-old girl despite being widely held to be innocent.

Frank grew up in Brooklyn and eventually moved to Atlanta, home to the largest Jewish community in the US South, where he became the superintendent of a National Pencil Company factory. He was openly Jewish and even served as president of the local B'nai B'rith chapter.

However, a young 13-year-old girl named Mary Phagan was found murdered in the early hours of April 27, 1913 inside the factory basement. Phagan had been an employee of the factory and had come the previous day to collect payment when she was evidently brutally murdered.

Based on the evidence found at the scene, police believed she had been killed on the second floor of the factory - where Frank's office was located - and later moved.

Soon, Frank was arrested and charged with her murder. There were some in the police who thought from the start that he was guilty, and an attempt to enlist the help of detectives from the Burns Agency. However, as noted by historian Steve Oney, the agency had withdrawn from the case. The agency, Oney wrote in the words of detective C. W. Tobie, "quickly became disillusioned with the many societal implications of the case, most notably the notion that Frank was able to evade prosecution due to his being a rich Jew, buying off the police and paying for private detectives."

The trial and investigation had been plagued with controversy from the start. As noted by historians, members of the press had already been heavily sensationalizing the entire incident. Much of this was made easier by capitalizing on existing social tensions but also drew from the fact that Frank was a rich Jew with a northern background - having been raised in Brooklyn, despite being born in Texas — who managed hundreds of young girls working long hours for low pay.

What also stands out about the trial was the prosecution's key witness, Jim Conley, a black janitor. The fact that the testimony of a Person of Color was accepted by a court in Jim Crow-era Atlanta was itself noteworthy. Especially considering evidence that Conley himself was the murderer, and his testimonies were filled with considerable contradictions. However, as recounted by Encyclopaedia Britannica, racism had actually worked in Conley's favor, as the prosecution and jury had "[Dissmissed] Conley’s lies as a function of his race... believing that any black person would be incapable of remembering such a complex story unless it were true."

In addition, it also shone a spotlight on antisemitism in the region. According to an article in the New York Sun on October 12, 1913, antisemitism certainly was present in the trial. "The [antisemitic] feeling was the natural result of the belief that the Jews had banded to free Frank, innocent or guilty. The supposed solidarity of the Jews for Frank, even if he was guilty, caused a Gentile solidarity against him," the article wrote, as noted by Oney.

This was further supported by other historians. According to Prof. Nancy MacLean of Duke University, the case and accompanying antisemitism "[could] be explained only in light of the social tensions unleashed by the growth of industry and cities in the turn-of-the-century South. These circumstances made a Jewish employer a more fitting scapegoat for disgruntled whites than the other leading suspect in the case, a black worker."

After a long sensationalized trial with appeals even going to the US Supreme Court, Frank was ultimately sentenced to death, though then-governor John Slaton commuted the sentence in June 1915 while Frank sat on death row.

This, however, was not the end of the story. Outraged at the commuting of the sentence, a group of men kidnapped Frank from prison and drove him to Phagan's hometown of Marietta. There, they lynched him from a tree, killing him. The lynch mob themselves were never identified or faced charges, and as such never faced any consequences. This is despite the fact that the lynching itself was photographed, with the members of the lynch mob clearly visible and identifiable in the picture.

The picture itself was widely circulated and was sold as popular postcards.

The incident was shocking with considerable historic implications. It shone a spotlight on the antisemitism present in the US South. As recounted by Oney, according to The Forward, it forced a widespread exile of Georgia's Jewish community, and many who remained became in response increasingly less visibly Jewish in their actions, customs and appearances. "They became even more assimilated, anti-Israel, Episcopalian. The Temple did away with chupahs at weddings – anything that would draw attention."

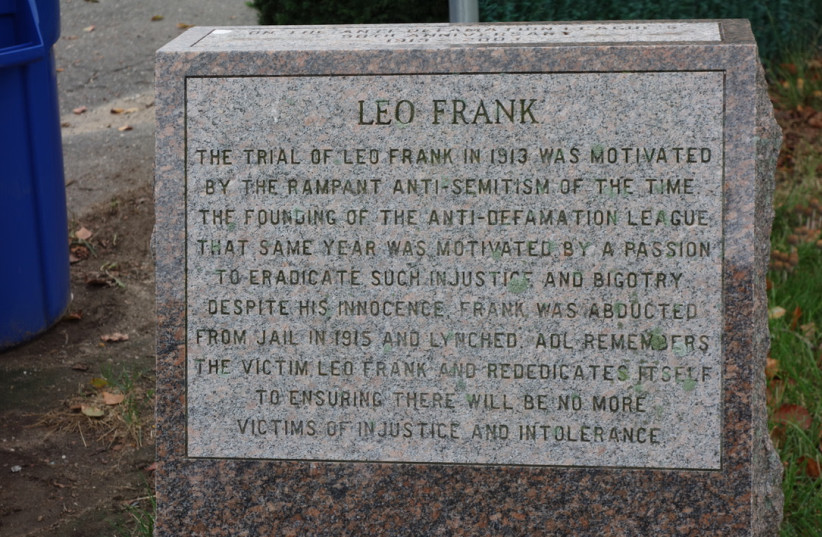

The trial had been accused of being motivated by antisemitism from the start, and many observers from the onset and until this day maintain Frank's innocence.

His conviction had helped inspire the establishment of the Anti-Defamation League, the American-based NGO that acts as a watchdog for antisemitism. However, it also helped inspire the resurrection of the infamous white supremacist organization known as the Ku Klux Klan. This "second" Klan, as it is known, was formed with the burning of a massive cross atop Georgia's Stone Mountain. It was this iteration of the KKK that introduced the now infamously iconic symbols of burning crosses and wearing white robes with pointed hoods.

Multiple attempts were made to posthumously pardon Frank, which finally succeeded in 1986, but this was not done to exonerate him, rather it was done because it recognized the "State's failure to protect the person of Leo M. Frank and thereby preserve his opportunity for continued legal appeal of his conviction, and in recognition of the State's failure to bring his killers to justice."

Attempts to exonerate Frank posthumously have been met with failure. However, another attempt was started in May 2019, when Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard announced they would reopen Frank's trial with a newly-created cold case investigation unit. However, there have not been any further developments on the case.

However, though over 100 years have passed, the subject remains controversial, with several sites in 2013 - the centennial of Phagan's murder - insisting on Frank's guilt, something that was condemned by the ADL.

"The Frank case opened a deep vein of antisemitism in America, unleashing furies that remain part of the national psyche," Oney wrote in a 2019 article in Atlanta Magazine following the announcement that the case would be reopened. "As a result, any discussion of the subject is difficult. Emotions about it run strong, and, while a majority now believes the factory superintendent was guiltless, others resent what they regard as a knee-jerk acceptance of that fact. Howard’s investigators will need to keep this in mind if they are to vindicate Frank. The affair pitted Jew against Gentile, white against black, rural against urban. Regardless of the outcome, not everyone will be happy."