THE Sygna shipwreck might be gone, but it has not been forgotten.

Wednesday marks the anniversary of the shipwreck, which sat watching over Stockton Beach for more than four decades. Being Australia's largest shipwreck, it was an extraordinary sight.

The story of the Sygna shipwreck starts in 1974 when tumultuous weather saw the ports of Sydney and Newcastle closed. As huge swells pummelled the coast a warning was issued for all ships to move out to sea, but the captain of the Sygna decided to remain. On May 26 the 53,000 tonne Norwegian bulk carrier ran aground and all 31 trapped sailors had to be rescued from the vessel.

The Sygna was later split in half during a salvage operation, but the stern remained a landmark on Stockton Bight beach for more than 40 years.

Mid 2016 the wreck was finally swallowed by the ocean.

MEMORIES OF THE STORM

by Greg Ray

ASK most older Newcastle people where they were on the night the Sygna went aground and they'll probably be able to tell you.

The killer storm was a once-in-a-lifetime reminder of nature's awesome power. During its 150-minute peak the gale, with gusts of up to 170km/h, buffeted the whole region and caused incredible damage.

At Terrigal, a 19-year-old man drowned when huge waves smashed across a camping ground and hurled the car in which he was sitting into the ocean. A newly finished house in Francis Street, Swansea, literally disappeared at the height of the storm. Pieces of the building and its foundations were later found more than a kilometre away.

Another house, at Brightwaters, was lifted and removed from around its startled occupant who was left unharmed to contemplate his property's brick foundations.

Other homes either disintegrated or were so badly damaged they had to be demolished in the following days. One Swansea home was destroyed by a fire that broke out during the storm, probably as a result of an electrical fault.

A timber church at Morisset was shifted more than six metres from its foundations and at Catherine Hill Bay half of a 200-metre jetty was destroyed. The Stockton ferry wharf was partly demolished and pieces washed up in Newcastle Harbour.

Police estimated 200 cars were wrecked or damaged. One was washed off Nobbys breakwater and crushed against a rock wall. Several motorists were injured in collisions as they tried to drive during the hurricane.

People cowered in their homes as countless television aerials crashed down on rooftops and windows smashed. Hundreds of blacked-out houses lost their roofs and live wires whipped and sparked in the screaming sky.

Trees splintered and fell. Caravans flew like kites, with one blowing more than 60 metres from its site.

For those on the water the fear was greatest. Lives were lost at sea as yachts were crippled and sunk by the monster waves and howling wind.

In the lakes and bays yachts and cruisers snapped their moorings and were broken up on rocks or dumped in the yards of waterfront homes. One was found the next day halfway up a tree.

At Wamberal and Avoca waves crashed their way into beachfront houses, cascading through rooms and forcing residents to flee.

When daylight finally dawned residents were greeted by the sight of streets littered with tree limbs, pieces of houses, broken wires, stray shop awnings and broken glass. The clean-up, hampered by continuing rain and bad weather, took weeks.

That's the piece of weather that those who saw it will never forget.

But for all that, the hurricane is always known as ''the Sygna storm''.

While most people gritted their teeth by torchlight in the battered suburbs, praying their walls and roof would hold together, there was a heart-stopping drama unfolding in the busy port of Newcastle. And just offshore a giant steel ship was fighting a grim and losing battle with the sea.

The Sygna was just one of many ships waiting off Newcastle when the storm struck. There had been a surge in demand for coal and the port couldn't keep up with the loading schedule.

The seven-year-old, 53,000-tonne Norwegian freighter had arrived off Newcastle from Japan five days earlier and was waiting to load a cargo of 50,000 tonnes of Hunter Valley coal, destined for European customers.

In the middle of the afternoon of May 25, the Sygna's skipper, 57-year-old Ingolf Lunde, missed hearing the NSW Weather Bureau's gale warning for waters south of Kempsey.

Later, when he watched the TV weather report and saw the warning of 40-knot winds, he wasn't unduly perturbed. Winds of that speed were not unusual, he thought, and his ship could ride them out without too much trouble. Anyway, strong wind warnings had been broadcast over the previous few days and to Captain Lunde it may have all been starting to sound routine.

Until about 8pm the biggest wind gust had been 35 knots, but after 8.15 things got markedly worse. The wind swung around to the south-south-east and started gusting up to 50 knots.

The Sygna dragged its anchor at about 9.30, but Captain Lunde had the cable recovered, set a watch for the night and went below to sleep. By 11pm the weather watchers at Newcastle's Nobbys Signal Station were getting apprehensive and they warned the ships at anchor off the city that the storm was likely to get worse. Most of the ships took the hint, and by about midnight only three ships remained. The little Chinese-owned ship Cherry couldn't raise its anchors because the cables were tangled, and the Norwegian bulk carrier Rudolf Olsen was determined to stay put because it didn't want to lose its position as next in line for coal loading.

At midnight the winds died down a little: the calm before the storm.

A quarter of an hour later all hell broke loose, and so did six ships moored in Newcastle Harbour.

The harbour pilots and tug crews who had been expecting a quiet night suddenly found themselves in the middle of chaos and confusion. Winds of up to 70 knots were screaming across the water, snapping giant cables and sending huge ships careering around the harbour. No sooner was one secured then another was loose.

One ship, the Brisbane Trader, was among a group that had broken loose in the Steelworks Channel and it was lying right across the path of the drifting, engineless tanker Express, in the port for a refit. The Express had already been re-secured once that night and had broken free again. Now it had to be pushed onto a mudbank to keep it out of danger.

Another ship, the Man Lloyd, was tied up at Lee Wharf when all 18 of its cables parted (each was brand new polypropylene, 18 centimetres in circumference), and it went drifting into the crowded confusion of the harbour.

Some time around 2am the surging waters of the port snapped the communication cables that kept Nobbys Signal Station in touch with Sydney. The port was left with nothing more than a low-powered domestic radio link.

Shortly afterwards, the skipper of one of the harbour boats reported receiving a weak SOS signal. It was the Sygna, reporting itself aground and requesting two tugs to assist it. It was an impossibly optimistic request, given the hectic work to be done inside the port where the surge was so powerful even the tugs struggled to make headway.

The chances of a tug getting safely over the bar in those conditions were so remote as to be negligible. All Nobbys could do was to ask the sea-going tug Warrawee, based at Sydney, to standby in case it was needed.

The other two ships remaining close to shore were fighting for their lives. The Cherry, with its anchor cables still tangled, turned head to the wind and ran its engines flat out to keep its anchors from dragging. Its frightened crew didn't get the cables untangled until conditions improved after 8am, when the ship fled, belatedly, to the safety of the open sea.

The Rudolf Olsen, which had been reluctant to risk losing its turn at the coal-loader, almost finished up ashore. The ship was luckily able to raise just enough engine power to turn its bow into the storm and hold on through the ordeal.

Not so lucky was the bigger Sygna. Although a Norwegian inquiry exonerated the ship's officers from blame, there seems little doubt they might have saved their ship if they'd turned and run to sea between 11pm and midnight with most of the others. But at 11pm Captain Lunde was asleep. Even with the 10pm gale warning he heard or the dragging of the anchor in the storm's early stages, he didn't bother dropping the ship's second anchor. He went to bed and told his officer of the watch to wake him if the anchor dragged again. So, as the other ships around it left the area, the Sygna sat tight, swinging at its single anchor while the wind and sea rose around it.

By 1am the anchor let go and the ship was adrift. Captain Lunde, wide awake now, gave orders to weigh the anchor, but the weather conditions were so bad even this simple job became a major problem. By now the winds were gusting at 130km/h.

The captain ordered full speed ahead and full port rudder, finally deciding to head for the open sea.

Too late.

Full of ballast water and drawing about 9m, the Sygna was pushed sideways by the storm, bobbing up and down on the angry swell like a cork in a tub. The ship bounced on the bottom of Stockton Bight at least twice before it was pushed ashore and many believe it was one of these knocks that put the main engines out of action.

Unable to turn the ship's flailing head to the wind, Captain Lunde gave orders for a full starboard turn. A few minutes later, at 2.15am, Sygna was aground on Stockton beach.

The crew of 28 men and two women - mostly from the Bergen district in Norway - were not in immediate danger. Captain Lunde had already made some contact with the Newcastle pilot cutter and he also sent a telegraph message to his shipping agents in Newcastle. He wanted help to tow his ship, which he was not yet ready to abandon.

The harbour authorities planned to wait for daylight to assess the Sygna's plight. They had plenty on their plate already and there had been no call for a rescue of the crew.

After 4am the Sygna fired a red distress flare which was seen at Nobbys and which helped locate the stricken ship. Captain Lunde again requested tugs at 5am, but was told the bar was too dangerous for tugs to leave port.

As soon as daylight appeared, Newcastle Water Police took a four-wheel-drive along Stockton beach to where the ship was stranded. They reported it was hard aground, but the crew appeared to be in no danger.

This assessment changed at 7.30am when the police reported that the ship now appeared to have broken its back and might be starting to disintegrate. Oil was pouring from the ship and a crack had appeared in its side.

With news of the fractured hull, the Sydney-based sea-going tug - more than five hours away - was taken off standby. Williamtown RAAF was put on alert. The base agreed to supply a helicopter to evacuate the crew if requested.

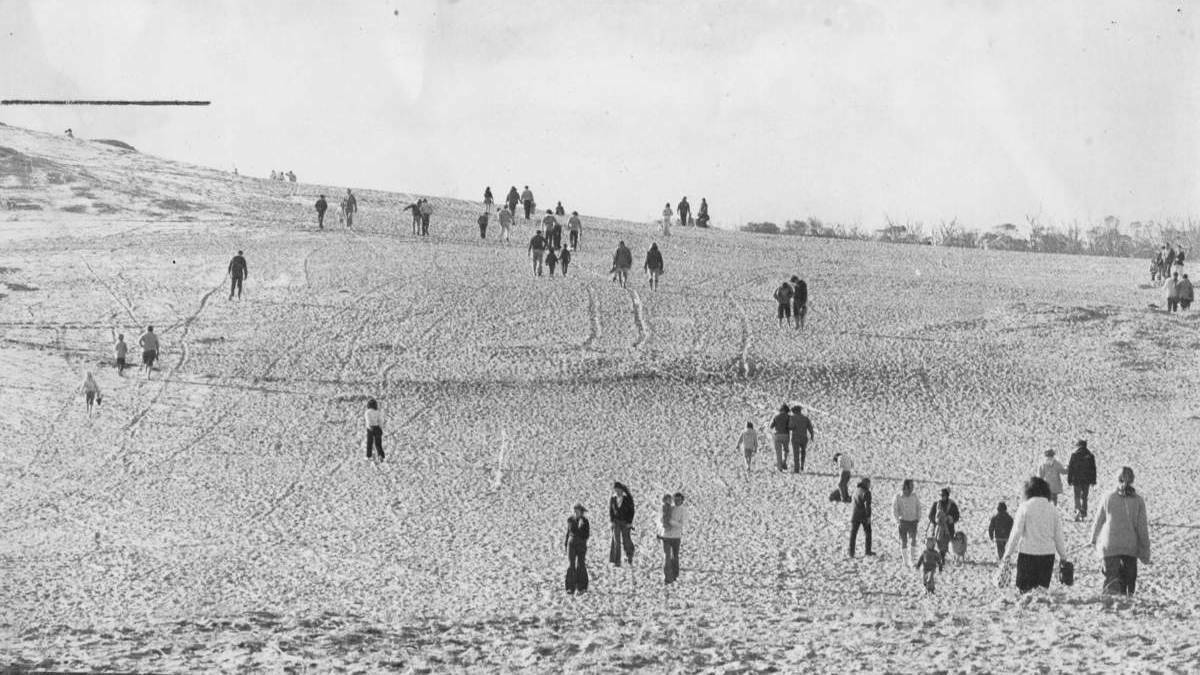

But first an attempt was made to remove the crew by lifeboat. Police fired a rocket line aboard the ship and Newcastle Herald photographer Ken Robson took his famous photograph of spectators and volunteers, rugged up on the rainy beach, hauling the line taut.

The lifeboat attempt failed, however. The boat's motor failed, the current was too strong and the danger was deemed too great.

By midday a helicopter was taking off from Williamtown and by 3pm the crew had been safely removed.

Captain Lunde, seemingly more worried about his ship now it was hard aground and doomed than he had been when it was lying alone on a single anchor between a gale and a hostile coastline, refused at first to leave. He had to be reassured that his departure would not cost the Sygna's owners their salvage rights.

Long after the storm had gone and most of the painstaking cleanup was over, the question of what to do with the giant steel hulk lying broken and leaking oil on Stockton beach remained.

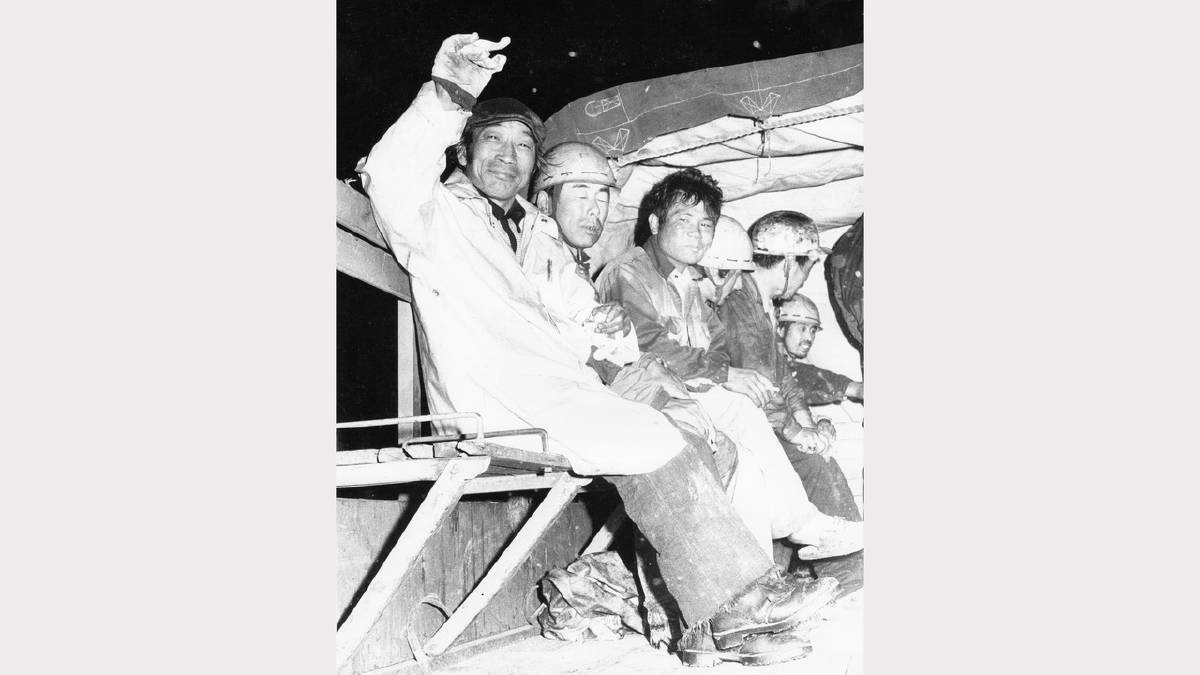

The man who won the salvage job nobody else wanted was an incredible character named Kintoku Yamada, of Japan.

Mr Yamada reckoned he had a debt of honour to pay to an Aussie ex-serviceman named ''Harry''.

A teenage survivor of the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima, Yamada had lost his father at the end of the war and he had been seriously weakened by recurrent bouts of tuberculosis. All his life he remembered the kindness of Corporal Harry, a member of the Allied occupation force, who gave him $100 and urged him to get an education.

Taking Harry's advice, Yamada studied economics, set up a salvage business and made himself a reasonable fortune. He came to Australia a number of times to try to find Harry, but when he finally discovered the man's identity he learned that Harry had died five years before and was buried in country Victoria.

At any rate, if Yamada owed any sort of debt to Australians, he paid it back with interest on the Sygna job.

Yamada's plan was to float the Sygna off the beach in two sections and tow them back to a Japanese shipyard to be rejoined and turned back into a useable ship. It was a good plan and if it had worked he'd have made money. But fate was against him from the start.

Standing just 1.5 metres tall, the feisty, jocular Yamada spoke fluent English and drank Aussie beer. The first thing he did on the Sygna when he arrived in August 1974 was to place a bottle of sake (Japanese rice wine) on a mast on the ship as a sort of good luck charm. It didn't work.

Yamada knew time was his enemy and he and his 23-man Japanese team of divers and engineers worked flat out, around the clock, on the Sygna job. They never walked if they could run and they never slept unless they had to. They were acutely aware that the longer the ship stayed stuck on the beach, the greater the damage to its steel plates and the smaller the chance of Yamada's gamble paying off.

He knew immediately Australian workers would never put in the same effort he and his team were prepared to and he made a decision to pay whatever was necessary to guarantee industrial peace and some measure of moderate efficiency.

The result was a massive workforce of Aussies - most of whom Yamada considered unnecessary but all of whom were paid very high wages.

He only wanted five Australians to work on board the ship with his own team and by all accounts the two groups built up a tremendous rapport.

It was the army of fetchers and carriers on the beach that caused the friction. He was forced to employ as many as 60 men, a large number of them painters and dockers.

Yamada thought many of them were obstructionist bludgers who'd bung on a demarcation dispute at the drop of a hat. And he didn't hesitate to tell them so, usually with a polite smile on his face.

Once, when a group of dockers was sitting on piece of equipment that was needed on the ship he yelled from the deck: ''Off your backsides and move - please.''

Finally he is reputed to have agreed to pay some of them just to sit on the beach and keep out of the way of those who were actually working.

Naturally those involved in the work recall things differently, and there was a tremendous amount of ill-feeling aroused whenever the Aussie workers were criticised, which was often.

Union delegates have since argued that the pay rates were not unreasonable for the work and have pointed out that the beach work involved 12-hour shifts - increasing to 24 hours when serious pumping began. They never divulged just how much their members were paid, however, simply explaining that it was ''a considerable amount''.

It was the manning scale, not the pay, that was bleeding Yamada dry, but pay became an issue when he wanted tugs to take off the refloated sections of the wreck.

It's hard to know, now that 30 years have passed, just what really happened when Yamada needed tugs at the Sygna.

On all the evidence now available it seems likely that Yamada offered to pay a hefty bonus to the tug men to keep them sweet. The tug men wouldn't have had a problem with that, but there is more than a hint of evidence to suggest that some towage companies were worried that this extra money might be seen as a precedent that could affect future work.

The unions offered to sign declarations that the Sygna payments would be a one-off, but the signs point to a management ''go-slow'' on the issue. Yamada was bled again.

As a stop-gap solution he hired the sea-going supply ship Lady Vera for three times its normal charter rate and paid bonus wages to a crew that amounted to twice its normal complement.

The Sygna refloated on September 6 and promptly, but not unexpectedly, broke in half. The bow section was towed to Port Stephens on September 10, leaving the stern - still holed and leaking badly - to be refloated another day.

When the expensive Lady Vera finished its job and moved off to a waiting contract, Yamada started seeking another tug. Tugs were available, but it seems towage companies were frightened of letting the crews be paid the sort of money that was earned by those aboard the Lady Vera.

Yamada's men, believing a deal would be done, kept working to refloat the stern section of the Sygna. But when they got it afloat there was still no tug and, after winching it painstakingly into deeper water, they were forced to let it settle again onto the sand.

Suddenly, a tug was available, but weather caused problems. On September 26 big winds whipped up and pushed the half ship back inshore, almost to the same point where it had rested before Yamada's men got it afloat.

After much more acrimonious and unproductive arguing between Yamada, the tug owners and the unions representing the tug crews, the sea-going tug Warawee was finally sent from Sydney in October.

And while the companies always claimed they paid the men no more than award rates it is commonly accepted that Yamada's hand was in his pocket again. Which was no more or less than he'd expected all along.

But now it was too late.

By November the stern section was structurally damaged from all the refloating and re-grounding. The salvage job, already incredibly expensive, had become unviable to complete. To November 18 the salvage effort had cost $1.6 million, with $600,000 of that paid to firms and workers in Newcastle.

The Norwegian insurer of the ship, Skuld, which had guaranteed a large chunk of the salvage cost, summed up the situation with brutal frankness: ''Mr Yamada is bleeding to death. He is the loser.

''The people in Newcastle are the only winners because of the money spent there in the operation. Yet their contribution was very limited.

''Yamada has smiled and paid. We feel very, very sorry for him. He was very optimistic when he bought the wreck. The Japanese crew were very capable and did good work. It is sad to have seen them work so hard for so little result. The workers from the Australian side worked very little and achieved an enormous amount of money.''

Before he went back to Japan, Yamada took the bottle of sake from the Sygna's mast. He tried to persuade the Norwegians and the Australian government to finance one more try but nobody wanted to get involved.

The 116-metre bow section of the ship - containing 4000 tonnes of steel - remained anchored at Port Stephens for more than 18 months before it was towed to a shipbreaker's yard in Taiwan.

The stern section sat on Stockton beach until 2016, a favourite spot for photographers, fishermen, surfers and four-wheel drivers. Its rusting hulk was starkly and strangely beautiful: a reminder of the tremendous power of the angry elements and of a storm that left its mark on a generation.