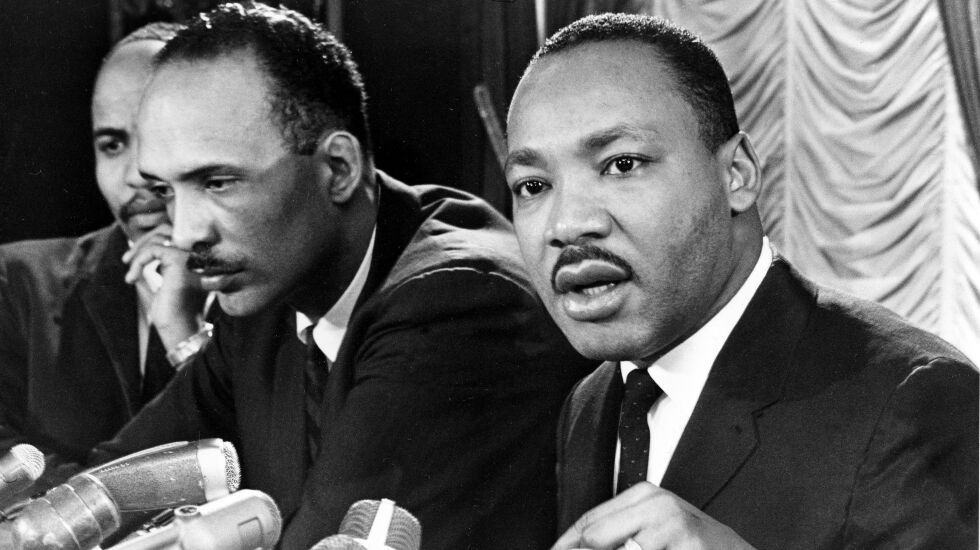

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was not a tall man. Five-foot-7 at most, and prone to pudginess. His grandeur was not physical, but moral, verbal, philosophical and spiritual. When he opened his mouth, he donned wings and would soar, taking his audience along with him.

Except, of course, for those left earthbound, who remained unmoved by his vision of an America where people are not judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.

Maybe that’s why I never cared for the King Memorial in Washington, D.C. First, the statue doesn’t look enough like him. Second, the entity honoring King is the same federal government that allowed the FBI to hound him, bugging his hotel rooms and tapping his phones, peddling his darkest secrets as punishment for the crime of trying to make the country a better place.

Even setting that aside, the government rendering the man into granite 30 feet tall is still a two-edged honor. Official approval helped and hurt him. One of the many challenges King faced was being co-opted. King was a man squeezed — haters to the right, radicals like Malcolm X to his left, impatient young people pushing up from below, inert officials clucking concern from above.

For the past few weeks, I’ve been immersed in King’s brief life and turbulent times because I’ve been lucky enough to get my hands on an advance copy of “King: A Life.” The first major biography of King in decades is written by Jonathan Eig, the Chicago author of “Ali: A Life,” the truly excellent, bestselling biography of Muhammad Ali (and the truly excellent, bestselling biography of Al Capone and the truly excellent, bestselling ... well, you get the idea).

“King: A Life” is such a nuanced, detailed biography, it’s like having Martin Luther King sitting in your living room, reading a newspaper. Every day, I get to join him, to hurry downstairs, pour myself a cup of coffee and get to know the man better. You’ll have to wait until May when it’s published, but don’t worry, I’ll remind you.

I’m mentioning it now, prematurely, because Monday is Martin Luther King Jr. Day, and this year is the 40th anniversary of the establishment of a federal holiday honoring King. Understanding his vision is more important than ever. We live at a moment when not only are the civil rights that King fought for still unrealized, but even the history of that struggle is in danger as the sort of hidebound haters who sneered at him while he was alive, still among us, now push back against him. As always, they cast themselves as the victims, oppressed, their supposed right to reject anyone unlike themselves draped in patriotic bunting and touted as freedom.

Paying lip service to King is part of that scam. Thus you find far-right radicals quoting him, selectively, while whitewashing the King holiday, as Eig writes in the Tribune, into a sort of “consolation prize after it had become clear that America had given up on the kind of massive social reform that King had advocated.”

Those of us still trodding the path toward an inclusive future that King blazed will welcome the arrival of a new landmark biography of King in all his complexities and contradictions, his frequent glory and regular failings. I thought I knew about King, but the details in Eig’s book surprise and fascinate, such as for his first 20 years of life, he was called “Mike King.” As a child, he wanted to be a fireman. He bit his nails.

Eig’s meticulously researched book draws upon sources never before available. It should make waves like a cinder block dropped in a kiddie pool when it arrives this spring.

You don’t have to be Nostradamus to see why. Those against what King preached, still, will seize on the same personal flaws that King’s contemporaries used to try to undercut his message — his serial adultery and early plagiarism — as if only an innocent lamb is entitled to oppose a deeply unjust system. Those who adore King, unconsciously playing this game, will reject those undeniable truths, or object to their being included, while others will question why Eig, who is white, should be allowed to spend six years of his life researching and writing a gripping, groundbreaking new standard for telling the disappointments and triumphs of America’s only 20th century Founding Father.

As if everything King said had flown past them, too.