AT A GLANCE

- About 36,000 overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) have returned since the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

- Delays and inefficiencies in testing and processing documents have forced some 24,000 OFW who reportedly tested negative to remain in quarantine over the mandatory 14-days.

- While President Rodrigo Duterte ordered agencies to bring home OFWs, they feel neglected by government officials who were slow to respond to appeals for help.

MANILA, Philippines – The flight landed close to midnight on the first day of May. Dreary and sleep-deprived, passengers shuffled out of an airplane into the cold hall of an empty gate at Terminal 1 of the Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA).

Aeron Orqueta, who worked for a Japanese construction firm, carried nothing but a backpack as he sat in a room full of strangers. Since the pandemic took hold, he yearned for home after traveling from Matarbari, Bangladesh, the site of his company’s latest project.

The last time he had been home was Christmas.

Forced to leave their work abroad and uncertain over future job prospects, the homecoming is bleak. OFWs are welcomed not by warm family embraces, but terse orders of government handlers in hazmat suits herding them into quarantine.

By deciding to get on a plane back to the Philippines, he is one of the roughly 36,000 overseas Filipino workers (OFW) who have returned to the country since the coronavirus broke out in early January.

Unlike most countries, the Philippines faces the steep task of accounting for thousands of OFWs returning from jobs overseas. That means testing and isolating every single person who arrives from abroad to avoid an increase in transmissions of the coronavirus disease.

Based on guidelines from the government’s coronavirus task force, OFWs’ quarantine, testing, and transportation expenses would all be paid for until they completed all necessary health protocols.

Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque called it "VIP treatment" for overseas workers.

But for months, OFWs have been languishing in prolonged government quarantine. Many have complained of errors and inefficiencies that kept them in quarantine far longer than the mandatory two weeks, and even exposed them to the risk of contracting the virus.

Rappler spoke with several of them and their experiences revealed problems in the following:

- Access to testing

- Waiting for test results

- Obtaining quarantine certificates

Their ordeal reveals a country still trying to get its act together in the middle of what some OFWs described as the “quarantine game.”

No action, no tests

Right after landing in Manila, Aeron had to fill out a series of mandatory documents on his health and travel history. He was then given a rapid antibody test for COVID-19 – whose results he never found out.

Exhausted from 4 days of travel, Aeron ignored this and immediately looked for a ride to a quarantine-approved hotel. His company had booked him a room at the Conrad Hotel in Pasay City, so he could work while in isolation.

Because their accommodations weren’t coursed through the government, Aeron and his 12 companions had a hard time getting on a Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) shuttle to their hotel.

Over the next week, Aeron pounded government agencies with texts and emails for assistance. He and his co-workers needed a swab test to get out of quarantine, and were paying some P500 per meal for room service, which was the only option available.

Aeron reached out to the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA), PCG, Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), and Office of the Vice President but was either ignored or tossed from one office to another.

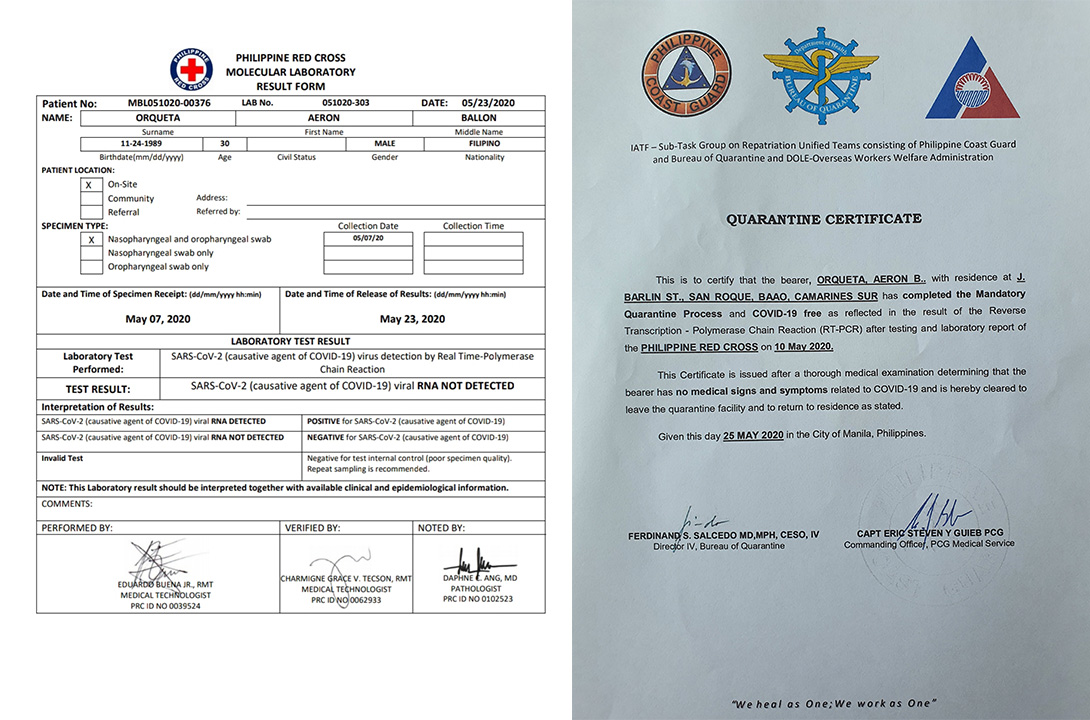

Frustrated, he contacted the Philippine Red Cross and agreed to pay P4,500 for a swab test. His colleagues did the same and they were charged another P9,000 for 3 shuttle trips to the Red Cross headquarters in Mandaluyong for their scheduled tests on May 10 and 15.

It took OWWA 10 days to respond to Aeron’s email. On May 20, the agency started covering expenses for the remaining 6 days of Aeron’s quarantine before he was allowed to return home.

Before that, his Japanese employer had to shoulder the workers’ first 19 days in quarantine – just so they could continue working despite the pandemic.

The mandatory quarantine period is only 14 days but without a negative result from a swab test, OFWs cannot leave isolation.

Waiting game

For OFWs quarantined in large groups at government-accredited hotels, swab tests come free. But it’s one thing to get tested and another to get the results.

On May 30, Michael,* a cruise ship photographer, counted his 32nd day in quarantine, and his 23rd since he and 86 of his shipmates were swab-tested at their hotel along Timog Avenue in Quezon City. They were told the results would be out in 3 to 5 days, but the weeks plodded on with no news from the Red Cross, which does the actual testing, or the PCG, which publishes the results online.

On May 25, 70 of the 87 names appeared on the PCG’s list of negative results. Michael scanned the list but didn’t find his name. Heartbroken, he and his roommate listened jealously to the sound of their shipmates dragging their luggage down the hallway to go home.

The 17 seafarers left behind started to feel desperate. Michael dialed the Red Cross but the voice on the line said they didn’t release individual results. He then called the PCG but was told that if his name wasn’t on the list, then it meant the Red Cross didn’t release his result.

He even tried calling the government’s 888 complaints hotline, but the operator only said they would relay his concern to the appropriate agencies.

Michael ended up more frustrated.

From their home in San Pedro, Laguna, Michael’s wife also started to phone the Red Cross to follow up on his case – to no avail.

Still stuck in his hotel room, Michael grew even more anxious. He read in the news that some 490 Chinese workers at Fontana Leisure Park in Pampanga got their swab results in just 4 days – when he and many other OFWs have been waiting weeks, even months for their results.

His roommate, who had been able to get a hold of his swab result, also packed up and left for home. Alone, Michael felt the full weight of his situation.

"It’s become quite depressing here," he told Rappler in a message.

Delayed certificates

Even in cases where test results come out on time, OFWs have to wait for certificates from the Red Cross and the government. Protocols require each worker to show proof they’ve tested negative for the virus and have completed the mandatory quarantine process.

This became the problem for Krissa Joy Mangilog, whose name was on a list of OFWs who tested negative on May 14. The motel reception called to congratulate her on the good news that day.

"Thanks. So I can go home now?" Krisa asked the receptionist.

She had been in quarantine for 15 days, since arriving on April 28 from Dubai where she worked as a restaurant team leader. Suffocated by the two weeks she had spent in a windowless motel room in Quezon City, Krisa was aching to leave.

"We can’t let you go unless you have a certificate from the Red Cross," the receptionist told Krisa.

"How do I get that certificate?" Krisa asked. The lady on the other end had no idea.

Krisa spent the next 3 days trying every line she had to authorities or anybody who might know how to get a copy of her test results. Not one person could answer her.

On May 18, Krisa and the 101 other OFWs quarantined at the motel were called to the roof deck for a meeting. Motel managers sensed they were getting restless, and had them fill out documents to supposedly fast-track the release of their Red Cross certificates.

The managers assured them they would be on their way home in 7 days. But this was bad news to many of the OFWs. With another week in limbo, some returned to their rooms sobbing.

Two days later, on May 20, Krisa’s Red Cross certificate became available on the PCG website. All she needed to do was show it to the OWWA officers at the lobby when her family or local government came to pick her up.

"But I am from Aklan! No one will come for me here!" Krisa tried to reason with the motel management when they told her she could only leave if someone came to get her. Desperate, she tried logging on to OWWA’s “Uwian Na” website to sign up for a ride home, but it was not working at the time.

In the end, she begged management to be given a contact from OWWA, whom she called immediately. The OWWA officer put her on the waiting list for a flight to Iloilo, where a bus would take her to her home province of Aklan.

Exposed to risk

Health protocols require OFWs to go on quarantine upon arrival to isolate them as possible carriers of the coronavirus. But prolonged quarantine also poses the risk of the virus spreading among them.

On May 21, Krisa and several other OFWs were in their rooms when they heard a commotion in the hallway. When they stepped out, what they saw left them shaken.

People in PPE had come to collect a woman who tested positive for COVID-19. The woman, who was sharing a room with her husband and child, was taken to a hospital facility.

The patient was asymptomatic, Krisa said. Rappler called the patient but she declined to be interviewed.

Krisa later learned that the patient was informed about her positive result only on May 20 – 9 days since they were swabbed. It took another day for a medical team to come and pick her up.

Krisa was worried she and other OFWs at the motel could have been exposed to the virus all along. A health response team should have come for the patient as soon as her test result was out.

The risks didn’t end there. On May 25 at 12:30 am, a government-chartered bus finally came to pick up Krisa and several other OFWs for their flights later that day.

"It was a mess. So disorganized!" Krisa said, describing the scene when she arrived before dawn at the airport. Terminal halls were packed with crowds of workers who filled corners of the airport as they waited for their turn to check in.

Krisa spent the next 8 hours in the terminal. Her flight to Iloilo wasn’t until 11 am.

The assumption must have been that all homebound OFWs had tested negative for COVID-19, Krisa thought, because no one seemed to care about social distancing.

Even on Krisa’s flight, every seat was occupied.

In Iloilo, she was put on a bus for the 4-hour ride to Kalibo, the capital of Aklan, where a van from her hometown Ibajay was waiting. Once in Ibajay, local officials brought her to a beach resort where she had to be quarantined for 14 days.

She was given another swab test, and if her result turns out negative, she can choose to finish the rest of her quarantine at home. It meant another 3 to 5-day wait but luckily for her, she was in a beachfront room with a view of the sea.

Krisa hopes to get a negative result soon so she can be home for the back-to-back birthdays of her mother and her sister in June.

Emotional, mental toll

Displaced from their better-paying jobs abroad, some OFWs decided to return home to be with family during the pandemic.

"We don’t know where to place ourselves," said Michael, the photographer who has been in quarantine for more than a month.

Far from the "VIP treatment," Micheal said it was as though he was a prisoner trapped and waiting to be sentenced.

Without any sense of control over their situation, these OFWs are on the verge of despair.

"Has the government abandoned us?" Michael told Rappler in a message. About a dozen of them were still at the hotel as of May 30, waiting for their test results.

As for Aeron, undergoing quarantine felt like navigating a game – with the odds stacked against them reuniting with their families. He had finally left for his home in Bicol on May 28, after 26 days of isolation.

"It’s so frustrating…Trying to request for help – it’s like no one is there. You’re tossed from one agency to the next so it adds to the stress and anxiety of waiting for your results. Is that the kind of support you receive? If you don’t follow up, nothing will happen," he said. – Rappler.com

*Name changed upon request

*Editor's note: All quotations have been translated into English

TOP PHOTO: COMING HOME. Overseas Filipino workers returning during the coronavirus pandemic go through a maze of coronavirus tests, quarantine, obtaining government clearances, and catching a ride to their home provinces.