The octopus is one of the coolest animals in the sea. For starters, they are invertebrates. That means they don’t have backbones like humans, lions, turtles, and birds.

That may sound unusual, but actually, nearly all animals on Earth are invertebrates — about 97 percent.

Octopuses are a specific type of invertebrate called cephalopods. The name means “head-feet” because the arms of cephalopods surround their heads. Other types of cephalopods include squid, nautiloids, and cuttlefish.

5. What do octopuses eat?

As marine ecologists, we conduct research on how ocean animals interact with each other and their environments. We’ve mostly studied fish, from lionfish to sharks, but we have to confess we remain captivated by octopuses.

What octopuses eat depends on what species they are and where they live. Their prey includes:

- gastropods, like snails and sea slugs

- bivalves, like clams and mussels

- crustaceans, like lobsters and crabs

- and fish

To catch their food, octopuses use lots of strategies and tricks. Some octopuses wrap their arms — not tentacles — around prey to pull them close. Some use their hard beak to drill into the shells of clams. All octopuses are venomous; they inject toxins into their prey to overpower and kill them.

4. Where do octopuses live?

There are about 300 species of octopus, and they’re found in every ocean in the world, even in the frigid waters around Antarctica. A special substance in their blood helps those cold-water species get oxygen. It also turns their blood blue.

You can find octopuses at different depths too. Some are found on warm tropical reefs just a few feet below the surface of the water. Others live deep in the sea, practically in the dark. The species that goes deepest is the dumbo octopus, spotted at 22,800 feet down – that’s more than 4 miles (almost 7 kilometers).

3. How smart are octopuses?

Octopuses are at the head of the class. They are among the smartest invertebrates on Earth. They have nine brains — one mini-brain in each arm and another in the center of their bodies. Each arm can independently taste, touch, and perform basic movements, but all arms can also work together when prompted by the central brain.

Octopuses put their brains to good use. They can solve mazes and puzzles, particularly when food is the reward. Sometimes they even outsmart people: At the New Zealand National Aquarium, Inky figured out how to sneak out of his tank and escape to the ocean through a drainpipe.

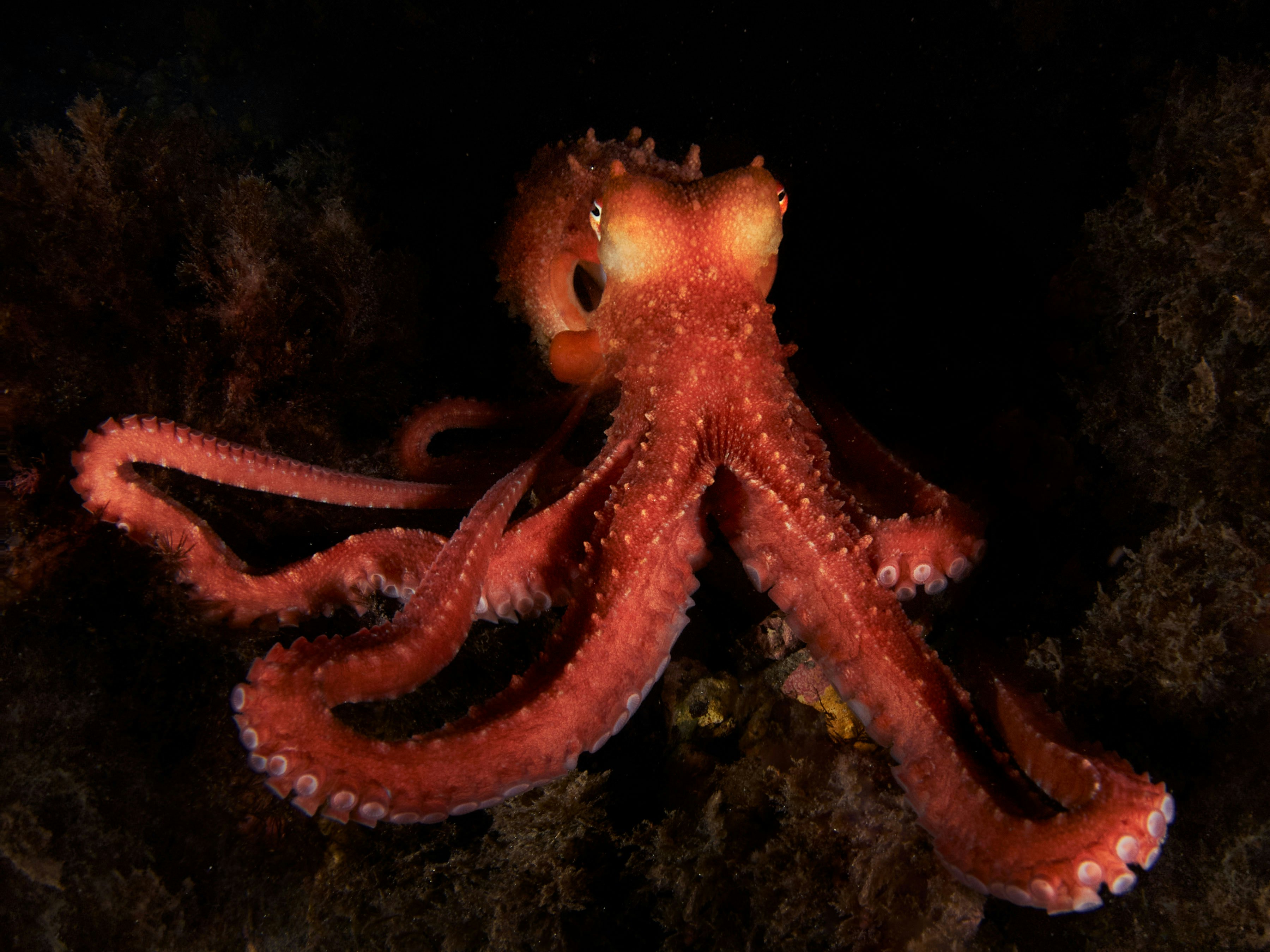

2. How do octopuses change color?

Octopuses are experts at disguising themselves so they can blend in with their surroundings. One way they do it is by changing color. Special cells, called chromatophores, receive a signal from the brain to tighten the muscles to show more color or loosen them to show less. Blue, green, pink, gray — they turn those colors and more to hide from predators, attract mates, draw in prey and warn enemies to stay away.

Some species also change their skin texture, making it smoother or bumpier, so they can camouflage themselves in rocks and foliage. Some spray ink when confronted by predators like sharks; this allows the octopus enough time to swim to safety.

The mimic octopus is particularly clever. It moves its arms in particular ways to imitate other ocean animals. For example, if it wants to look fierce, it extends two black-and-white striped arms out wide to look like a venomous sea snake. Or it flattens itself along the seafloor, arms next to its body, to look like a poisonous flatfish.

1. The octopus at risk

When confronting humans, an octopus tends to be nonaggressive — just as long as you give them space like you would any ocean animal.

Although octopuses have ways to avoid predators, they remain at risk from other threats: chemical pollutants, marine debris, habitat loss, overfishing, and climate change.

But all of us humans can help by making ocean-smart choices. That includes learning how to cut back on carbon emissions and using less plastic. Doing these things will help the octopus, and other marine creatures not only survive but thrive.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Erin Spencer at Florida International University and Yannis Papastamatiou at Florida International University. Read the original article here.