Many of us assume that everything a musician sings emerges from some autobiographical impulse. Pop music lyrics in particular are often read literally by fans as transparent disclosures about the singer’s life.

For some reason, this seems to apply solely to lyrics. Writers from other media, such as film and TV, are generally presumed to create their characters and stories from their imaginations, rather than personal experience, even when writing in the first person.

As historian Michel Foucault says: “Everyone knows that, in a novel offered as a narrator’s account, neither the first-person pronoun nor the present indicative refers exactly to the writer or to the moment in which he writes but, rather, to an alter ego whose distance from the author varies.”

Indeed, people don’t tend to leap to the conclusion that Patrick Bateman of American Psycho is a window into the soul of Bret Easton Ellis. Nor that Breaking Bad’s Walter White is merely a caricature of his creator Vince Gilligan.

So why do so many of us immediately assume every Taylor Swift lyric is a thinly veiled critique of an ex-boyfriend? Or that every new Kanye track is a window into his mental state?

In his book This is Your Brain On Music, psychologist Daniel Levitin notes that when we listen to music we are letting the songwriter into our living rooms and bedrooms when no-one else is around – even letting them into our ears, directly, through earbuds and headphones.

It is unusual, he says, to let oneself become so vulnerable with a total stranger. It’s understandable, then, that we want to our songwriters to be similarly vulnerable, and so believe their songs to be an exchange of confidence between us and them.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

In 2016, such autobiographical assumptions were applied to Sorry by Beyoncé. Part of her award-winning album Lemonade, the lines “He only want me when I’m not there / He better call Becky with the good hair” saw the internet erupt with theories. Fans attempted to uncover who the singer could have been referring to. Few people seemed to consider that Beyoncé may simply have created a fictional character in a fictional scenario.

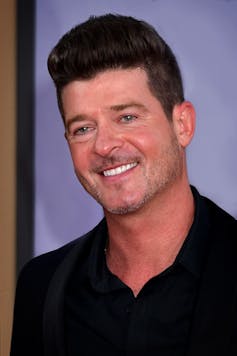

In 2013 the song Blurred Lines by Robin Thicke featuring T.I. and Pharrell was widely criticised for seeming to trivialise sexual violence, objectify women and reinforce rape myths. There wasn’t much room for debate about meanings in this song, but the fallout from the controversy suggests it’s the act of singing lyrics, rather than writing them, which makes people assume connection.

Hence it’s singer and co-writer, Robin Thicke – who also had a central role in the music video – has seen his career stall, while co-writer/producer Pharrell Williams has had multiple hit singles and recently celebrated the release of a Lego movie all about his life.

It’s true that the controversy around Thicke wasn’t helped by the fallout from his divorce and accusations of infidelity, as well as his live performance of the song with former Disney star Miley Cyrus at the 2013 Video Music Awards. But it does seem, as literary critics Raman Selden and Peter Widdowson put it, that listeners assume that “speech incarnates, so to speak, the speaker’s soul”, and that, as the “speaker” on Blurred Lines, Thicke is considered the one who supported its inadvisable and uncomfortable content.

Artist intervention

When an artist is inevitably asked “what’s the meaning behind this song?” and they give a literal answer, it immediately closes down the different ways a listener can interpret it.

Charli XCX, for example, when recently asked about the meaning of her song Apple, said: “I [wanted] to write a song about my kinda sticky relationship with my mom and dad.”

Once the writer’s intention, however vague, is revealed, the temptation is to elicit further meaning line by line. In the case of Apple, that has led to analyses such as: “‘I wanna grow the apple, keep all the seeds’ indicates a desire to nurture and preserve the positive aspects of [Charli’s Indian-Scottish] heritage.”

Contemporary artists don’t even have to wait to be asked. In December, singer Sam Fender announced the release of new song People Watching via an Instagram post, saying it was “about somebody that was like a surrogate mother to me and passed away last November”.

To those who didn’t read the post, the opening lyrics “I people-watch on the way back home / Envious of the glimmer of hope / Gives me a break from feeling alone” could hold any number of different meanings. But Fender has limited the possibility for other interpretations.

Think for yourself

Masters of the lyrical craft use imagery, syntax, allegorical language, rhyme, perspective and numerous rhetorical devices to create emotive, persuasive or life-affirming work. Work which can, of course, be as fictitious as any other literary work.

When it comes to figuring out what a song is “about”, then, perhaps it’s better to look at what it means to us personally. Levitin says listeners form more of a bond with a song when we need to fill in some of the meaning for ourselves.

Some songwriters invite such collaboration. John Lennon said he thought that whatever people make of his songs was valid. Neil Finn of Crowded House, meanwhile, claims he’s always happy when people get things “wrong” about his songs.

Some lyricists don’t even have a meaning in mind when they write. For the Weezer track Summer Elaine and Drunk Dori (2016), lead vocalist Rivers Cuomo drew lyrics from a spreadsheet containing a couple of thousand random lines. The resulting song suggests a coherent, real-life event but each line was actually from a completely different place and reassembled in an order that suggests a story that never happened.

In such cases, as the literary theorist Roland Barthes said in his essay The Death of the Author (1967), the author is only the person who writes the text. It is the reader – or, in our case, listener – who decides its meaning.

Glenn Fosbraey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.