Grammy winner and Pakistani singer Arooj Aftab said she has been a fan of qawwali maestro Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music since she was eight years old, as her parents would blast Khan’s songs in the car when she was living in Saudi Arabia.

“I can never forget those versions of Nusrat’s qawwalis, and how they resonated in my little body,” the 37-year-old Brooklyn-based artist told Al Jazeera via email.

Qawwali, which means “utterance”, is a form of Sufi devotional music with lyrics largely focusing on praising God, and the Muslim Prophet Muhammad and his son-in-law Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib.

Primarily sung in Urdu and Punjabi, and occasionally in Farsi, the genre dates back to the 13th century in the Indian subcontinent.

Salman Ahmad of Sufi rock band Junoon said the singing of the “Shahenshah-e-Qawwali” [King of Kings of Qawwali] “transported the listener to higher dimensions of mystical ecstasy and a yearning for the divine”.

“His Pavarotti-like vocal range of low to high would just give me goosebumps … his impeccable rhythm, pitch and the emotional tenor of his voice … it was soul stirring,” the 58-year-old Ahmad told Al Jazeera from the Pakistani capital, Islamabad.

Ahmad said Khan had great stamina and could go into the small hours of the night performing without compromising the quality of his singing.

Twenty-five years since his untimely death at the age of 48, Khan continues to inspire musicians in his home country and beyond. Songs like Dam Mast Qalandar and Ali Da Malang have been covered numerous times by artists across the subcontinent.

Rising qawwali stars and brothers Zain and Zohaib Ali say no matter where they travel to perform, audiences frequently ask them to play Khan’s songs.

“There are maybe two or three of our songs that people want to hear … mostly they are pleading with us to play their favourite Nusrat sahib [sir] qawwali,” Zain said from Lahore, Pakistan.

‘So creative and fearless’

Born in Faisalabad, Pakistan in 1948, and hailing from a family of well-known qawwali singers, Khan also sang ghazals – a form of romantic love and loss-themed poetry.

Khan began performing in the late 1960s. He received numerous awards worldwide, including the President of Pakistan’s Award for Pride of Performance in 1987 for his musical contributions to the country.

Junoon’s Ahmad believes what made Khan stand out among other qawwals was his willingness to experiment with styles of music.

“Khan was so creative and fearless,” he told Al Jazeera from Islamabad, Pakistan.

“He could jam with anyone … whether it was me or Jeff Buckley. He had no boundaries,” Ahmad said, adding that Khan took risks unlike the “purist” qawwals – citing the late singer’s collaborations with Indian and Western song-makers.

Renowned Indian lyricist and songwriter Javed Akhtar and Grammy-winning composer AR Rahman both worked with the Pakistani icon.

The 1996 ghazal Afreen, Afreen, written by Akhtar, remains one of Khan’s most well-known songs. The 2017 Coke Studio version of the track performed by Momina Muhtesan and Khan’s nephew Rahat has more than 370 million views to date on YouTube.

Rahat, Khan’s protege and musical heir, has had tremendous success in India as a playback singer – including for his improvisations of Khan’s qawwalis, tailored to suit musical preferences of Bollywood fans by using instruments such as guitars, synthesisers and saxophones to produce a poppier sound.

In the West, Khan first came to prominence in July 1985 when he performed at the World of Music, Arts and Dance (WOMAD) festival, co-founded by British singer-songwriter Peter Gabriel.

The concert, which was released as a live album in 2019 by Gabriel’s Real World Records, served as a stepping stone for Khan’s popularity across the world – and his future collaborations with Western musicians.

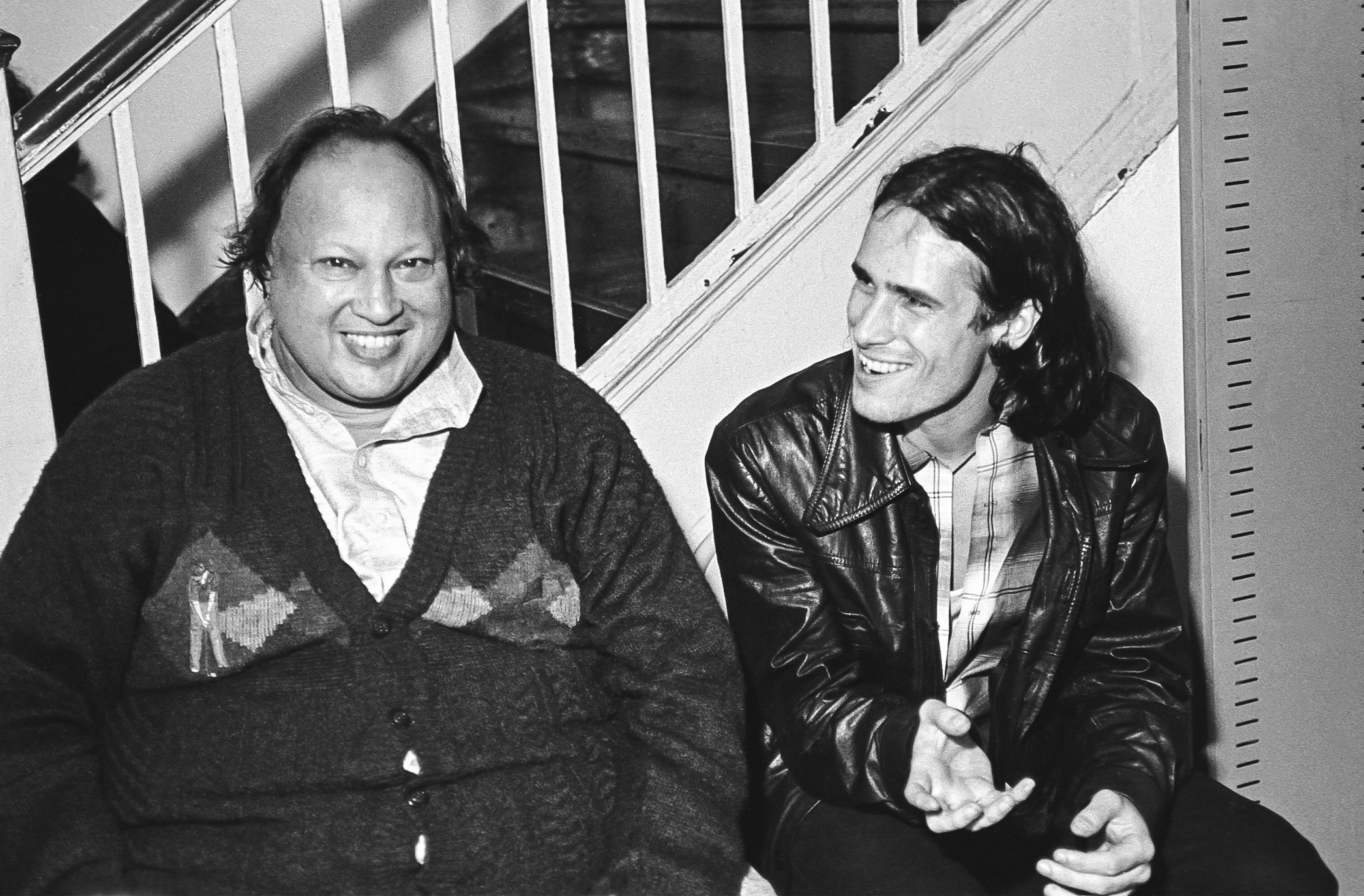

In 1990, Real World Records released Khan’s first fusion album Mustt, Mustt in collaboration with Canadian guitarist and composer Michael Brook. Six years later, Khan and Brook’s second album Night Song was released, garnering a Grammy nomination for Best World Music Album.

The New York Times called the fusion album a “Westerner’s dream of mysticism”, while Billboard USA called it “an album for the ages, solidifying Khan’s stature as one of the world’s pre-eminent singers”.

Speaking from Los Angeles, Brook told Al Jazeera that Khan was one of the “best singers” of the 20th century. “He is definitely in my top 10,” Brook said.

Having worked with him and watched him perform multiple times, Brook said Khan had a “magic stardust” quality whose passion and charisma “transcended both language and musical style … in a way that deeply connected with people”. Khan was selected by National Public Radio as part of their 50 Great Voices series.

Khan also contributed his voice to Western movies, most famously for the soundtrack of Martin Scorsese’s Last Temptation of Christ composed by Gabriel, and Dead Man Walking with Pearl Jam singer Eddie Vedder.

Musical influence

Brothers Zain and Zohaib Ali said Khan took a centuries-old art form and “made it easy” for today’s qawwals to keep the tradition alive in the 21st century.

“The qawwals who came before Khan Sahib would perform one qawwali for more than an hour, with whole shows going on for more than eight or nine hours a day. When Khan took up the mantle in the 80s and 90s, he figured that was not feasible – as most people didn’t have that much time to spare,” Zain said.

According to the 31 year old, Khan helped “modernise” the genre – while keeping intact its basic structure – by shortening qawwalis to 15-25 minutes, making them more accessible to a wider audience.

“Much of the qawwali played today is derived from Khan Sahib’s work,” Zain said.

Moreover, Zohaib noted that Khan’s large body of work has provided “more than enough material” for him and others to continue learning the Sufism-inspired art form for generations.

“Even today, despite being in this profession for over a decade, I’ll come across a Nusrat song or qawwali that I have never heard before,” Zohaib, 26, said. According to Guinness World Records 2001, Khan had released 125 albums – the most by any qawwali artist.

Junoon’s Ahmad, who was introduced to Khan by former cricketer and ex-Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan, said he owed the qawwal a “debt of gratitude” for the success in his musical career over the past three decades.

The band’s fourth studio album, Azadi, was “inspired by what I learned performing with Ustad [master] Nusrat”, Ahmad said, including the decision to use no Western drum sets in the 13-track playlist, and relying heavily on tablas and dholaks – local hand drums used extensively in qawwalis.

‘Timeless, ageless’

A month or so before Khan’s death, Ahmad said he attended a private performance of his and recalled how he was “not looking well at all”.

“He had been undergoing kidney dialysis … and I remember telling my wife that I wish he would take a break. He was doing too much.”

Not long afterwards, Khan fell gravely ill and was flown to London for treatment at the Cromwell Hospital, where he was pronounced dead on August 16, 1997 after suffering a heart attack.

Canadian composer Brook told Al Jazeera Khan was “cut down in his prime” – a time he personally felt the qawwal was starting to become “very intriguing” with the fusion song-making process the two musicians had embarked on.

Nevertheless, musicians like Ahmad and Aftab are certain that Khan’s body of work will remain relevant for decades to come.

“In the West, just like rock bands continue to reference the likes of The Beatles and Led Zeppelin, Ustad Nusrat’s songs will continue to be consciously or unconsciously sampled by the Indian and Pakistani singers,” Ahmad said. “His music is timeless and ageless. It will never die.”

For Aftab, Khan’s music was a “once in a lifetime kind of sound”.

“The command he had over the hours-long pieces was not only arresting but also invoked and invited a freedom to the listener,” she said. ”

“He freed a lot of voices … and he continues to do so, unparalleled.”