The fire that raged through Notre Dame has made us all look at this great cathedral differently. There’s no getting around it. If you have ever been to Paris, chances are you’re furiously ransacking your memories, digging back into past sensations and worrying about what lies ahead.

In 1914, months before the outbreak of a catastrophic war, Henri Matisse was doing the same.

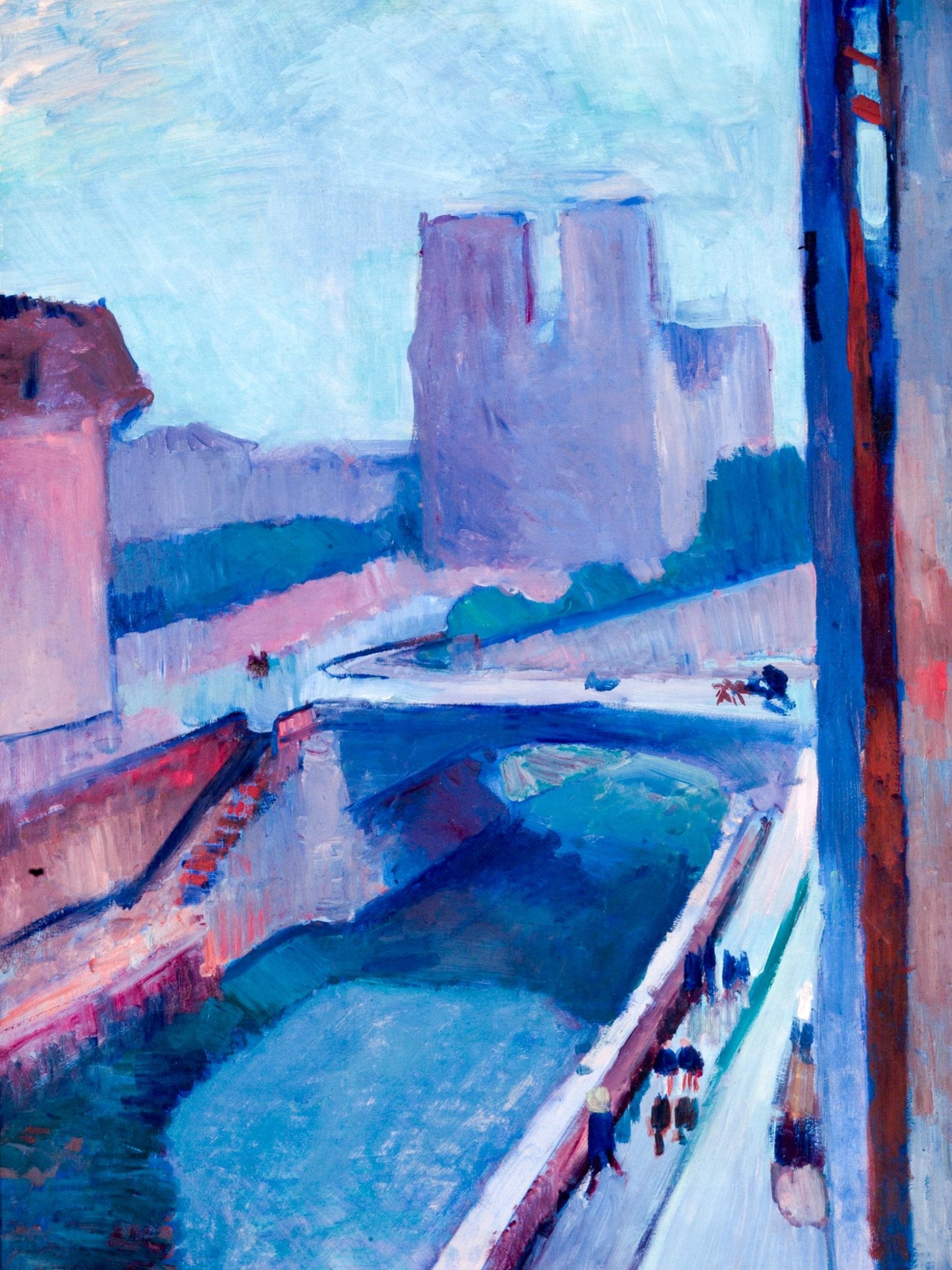

That year, the artist and his wife, Amélie, abandoned plans to go to Morocco and moved instead into a modest apartment with a view of Notre Dame, on the Quai Saint-Michel in Paris.

Matisse was 44. He had lived in the same building, one floor up, for years, beginning in 1899. In fact, apart from seven years of family life, he had spent his whole adult life living with this same view over the River Seine towards Paris’s most famous cathedral.

Back then, at the turn of the century, he had painted Notre Dame in broken impressionist brushstrokes (thinking, perhaps, of Monet’s great paintings of the facade of Rouen Cathedral) and as a ghostly, mauve silhouette under a light blue sky.

No details in that one. It was a strangely casual way to treat so grand a building. Matisse was acting with the heretical nonchalance of a radical painter, yes, but also with the nonchalance of a lover, of someone who knows something intimately and can treat it as a given, a birthright, without a tourist’s self-conscious reverence.

More than a decade later, the artist returned to the subject, with results that remain indelible – and haunt the psyche on a day like today.

Matisse was happy to be back in a part of Paris he loved. His chronic insomnia had shown signs of abating. He wanted, wrote his biographer Hilary Spurling, to strip his life “back to essentials”.

First, in oil paint so thin it reads as watercolor, he painted the same view, from the same position on the Quai Saint-Michel and with the same diagonal strip of the Seine cutting across the lower half of the canvas.

Then, he did something so radical he didn’t understand it himself. In fact, he refrained from exhibiting this second View of Notre-Dame, 1914, for 35 years, when his fears were confirmed. It was regarded as “an unfinished sketch to which Matisse had unaccountably signed his name”.

Matisse had reduced the cathedral to a shell, a linear scaffolding. He drew and redrew this shell, as if teaching himself its basic structure. He left evidence of his erased lines as he put down new ones, as if the painting were less a picture than a palimpsest, piled up layers of memory and sensation.

He then lightly smeared blue paint across not only the building’s facade, but also across the entire canvas. Apart from black, the only other colour he allowed was an oval-shaped patch of green, representing a tree or large bush in front of the cathedral.

All over the canvas, but especially around the building, you can still see evidence of scratching and scraping and incising lines.

Was it a painting of Notre Dame?

Not exactly. But neither was it abstract.

A painting, Matisse saw, was something, like memory itself, that was hard-won, boiled down, licked by fire. It needed to be built and rebuilt, and it was always changing in the minds of those who saw and loved it.

“Everything must be constructed,” Matisse told collector Sarah Stein – “built up of parts that make a unit … a human body like a cathedral.”

Above all, you could say, Matisse was attempting to represent in paint a process we’re all involved in now, as we contemplate a triumph of human faith, community, genius and sublime beauty that no longer exists as it did just yesterday.

What was that process? The overflow of remembered sensations into present ones.

In that overflow, surely, there is hope.

© Washington Post