School and career pathways for youth who grow up in northern regions look very different than those of their peers who grow up in the larger urban and southern areas of the country.

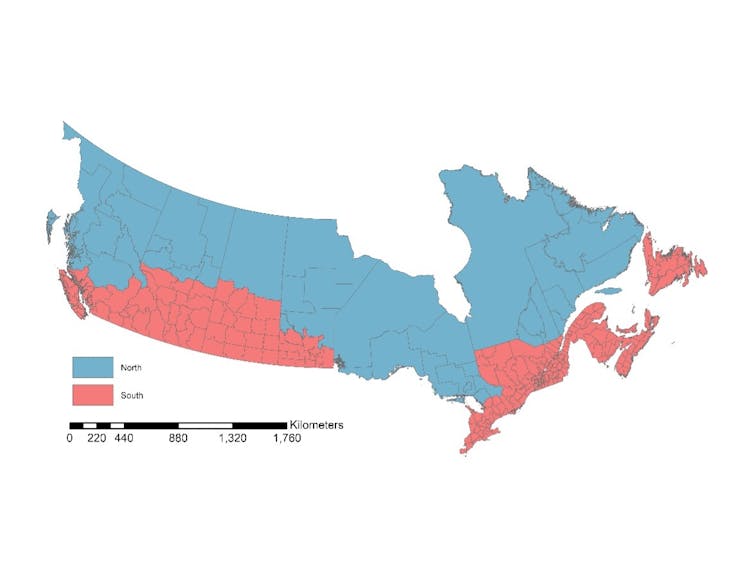

What’s known as Canada’s Provincial North is comprised of the northernmost parts of Canada’s provinces, excluding Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

But, despite the large geographical size of this area, the unique challenges facing residents in these parts of Canada often get overlooked. So much so, that some scholars have touted these regions as Canada’s “forgotten North.”

North-South gap in post-secondary access

New studies are shining a light on the education trajectories for youth in these regions.

Researchers are uncovering regional disparities in access to post-secondary education. Drawing upon Statistics Canada’s large-scale survey and administrative data sources, studies are revealing that northern youth are less likely to pursue post-secondary education. Among those who do, their timing of doing so tends to be later.

They also remain less likely to enter high-paying fields of study, like science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) programs.

School and work decisions for youth in the North are further complicated by a critical life decision: Should I stay in my home community, which offers fewer advanced schooling and career options? Or, should I relocate to a large, urban setting, where there is a richer and more diverse menu of post-secondary opportunities?

Many costs of uprooting

Attending a post-secondary institution that’s far away from home brings additional financial costs such as moving and relocation expenses, the costs of housing, buying food and returning home during school breaks.

Not to mention, some students also find uprooting themselves from their home community and family to be psychologically and emotionally taxing.

These challenges facing under-served communities in the North are compounded for Indigenous youth, some of whom are forced to leave their communities to access both high school and post-secondary education. Indigenous students are less likely to attend post-secondary education compared with non-Indigenous students.

Read more: Why there are so few Indigenous graduates at convocation

Limited northern colleges, universities

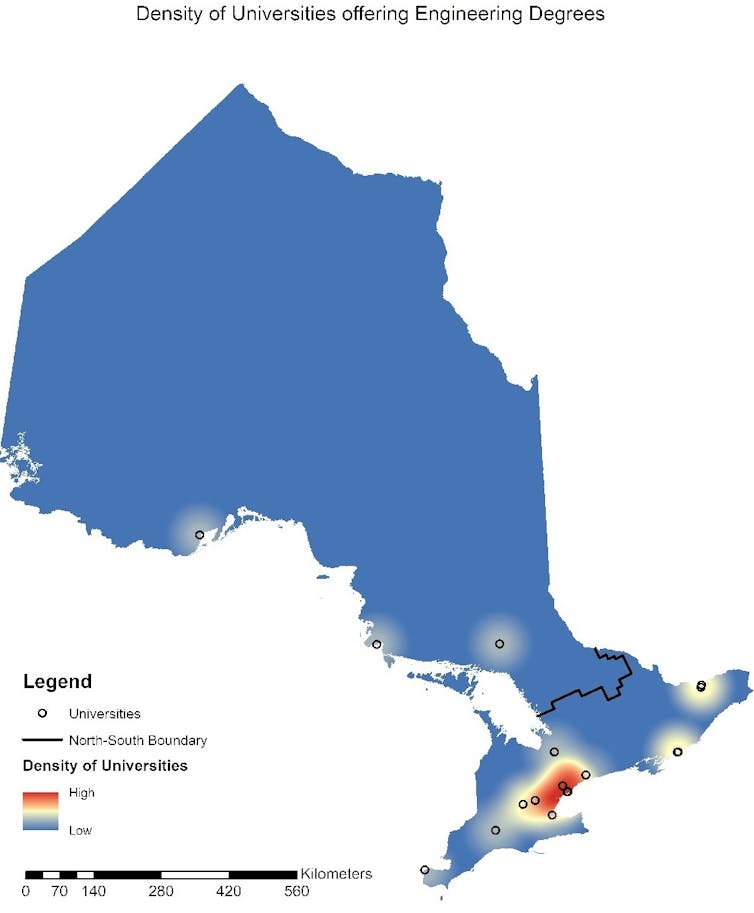

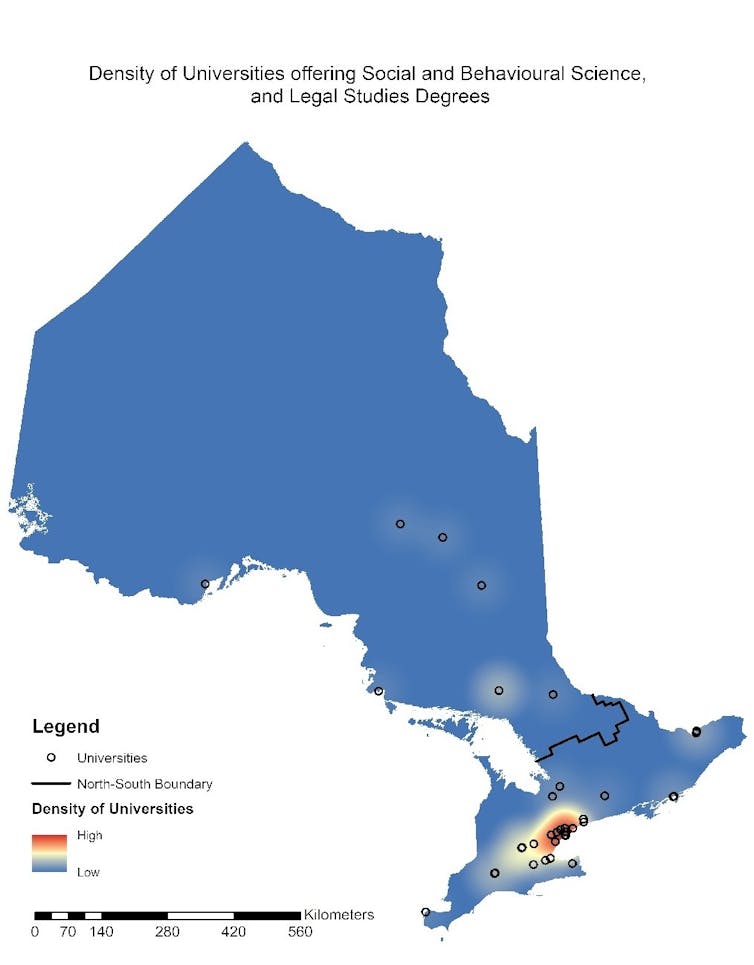

If we take a closer look at Ontario, we can see stark differences in proximity to post-secondary schools.

The vast majority of colleges and universities are packed into the Greater Toronto Area and spread throughout Southern Ontario. While Northern Ontario does have some post-secondary institutions located within a few of its urban centres (Thunder Bay, Sudbury, North Bay and Sault Ste. Marie), there are far fewer local options available.

Existing opportunities are more plentiful for generalist fields of study such as the social sciences or the behavioural sciences. Opportunities are considerably leaner for higher-paying, STEM-related fields of study such as engineering, and extremely sparse for graduate and professional schools (for example, schools of veterinary science and dentistry).

NOSM University, which began as the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, and which has buildings on the territory of Fort William First Nation in Thunder Bay, and the Anishinabek Nation in Sudbury, is a notable exception. Its aspirations to recruit and retain students from local and under-served populations may potentially offer a model for other professional fields.

Understandably, given the relative lack of options, many northern students are leaving their home communities to find a school or program that fits their needs. This context contributes to migration out of the community or “brain drain” of youth who leave, with very few who return home to work after graduation.

Ontario’s policy shift

Recent domestic tuition fee reductions and freezes in Ontario, coupled with lower domestic per university student funding, are putting some northern institutions in precarious financial situations.

Northern institutions rely much more heavily on government grants and tuition to fund their operations. Economically speaking, they are less “diversified” and entrepreneurial — meaning they cannot simply pivot their operations to seek out alternative sources of revenue.

Since the mid-2000’s, what’s known as Ontario’s “differentiation” policy has encouraged institutions in Ontario to attract and retain students using niche programs. A portion of government funding now depends on institutions hitting the performance metrics tied to this policy.

Read more: COVID-19 reveals the folly of performance-based funding for universities

Widening the gap in opportunities?

This shift in policy is making it more difficult for northern universities to balance their budgets. Some are facing difficult decisions around which programs might be put on the chopping block if they don’t bring in enough revenue.

These fiscal changes could have real consequences for student post-secondary access in the North. They could also contribute to a widening of the north-south gap in local post-secondary opportunities.

Some students affected when Laurentian University cut programs and announced the dissolution of the university’s federacy with other institutions said the brunt of the crisis was left on their shoulders.

For some students, the promise of living a better life may not necessarily be guaranteed by continuing their education due to the high cost of tuition. Unfortunately, the alternative might be that students forego further education entirely and find themselves in lower-skilled, poorly-remunerated segments of the workforce.

Ensuring long-term sustainability

Maintaining and enhancing local access to educational opportunities for those living throughout Canada’s Provincial North is vital to educating and keeping highly-skilled people in communities and to maintaining healthy economies.

The decision, to stay or to go, can have life-long impacts on youth’s personal, family and community life.

While new initiatives by the province of Ontario that promote remote education might open up options for some northern and rural youth, northern economies could miss out on the local economic benefits offered by post-secondary institutions if we go too far in this direction.

Rethinking funding models

Not only does the presence of local post-secondary institutions create better social and economic outcomes for local youth (especially low-income youth), it also fosters economic growth and economic resilience in local economies.

Providing educational and employment opportunities for those living throughout Canada’s Provincial North is vital to retaining strong communities and a healthy economy.

Keeping the local universities and colleges afloat in Northern Ontario requires a rethinking of the provincial funding model.

Avery Beall has received funding previously from Nipissing University and the Government of Ontario.

David Zarifa receives funding from Nipissing University, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), and the Canada Research Chairs (CRC) program.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.