Limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5℃ is getting harder. A recent UN report even stated that there is now “no credible pathway” to achieve this goal.

Our planet has entered uncharted territory, with all kinds of records being broken. For four consecutive days at the start of July 2023, Earth experienced its hottest day on record. And the North Atlantic Ocean is currently experiencing the highest sea-surface water temperatures ever recorded.

There is a good chance that many more temperature records will be broken in the coming months. A heatwave is currently sweeping across large parts of southern Europe, with temperatures expected to exceed 40℃ in parts of Italy, Spain, France and Greece. There’s even a chance that the current European temperature record of 48.8℃, could be broken.

Additionally, our new research highlights how dangerously under prepared northern Europe is for the consequences of climate change.

We found that, out of countries with more than 5 million inhabitants, Switzerland, the UK, Norway and Finland will experience the most significant relative increase in heat exposure and cooling requirements if global warming reaches 2℃. When we accounted for countries with populations of 2 million and over, Ireland came top.

Buildings in the northern hemisphere are primarily designed to withstand cold seasons by maximising solar gains and minimising ventilation – like greenhouses. The effects of extra heat are thus felt more acutely in these countries. Compared to other regions, the impact of even a moderate increase in temperatures will be huge.

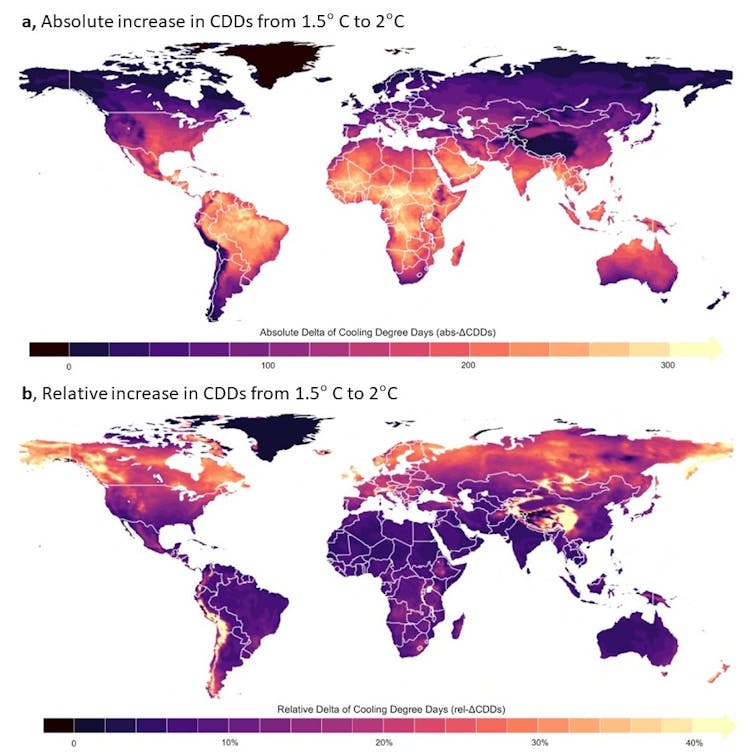

We modelled climate scenarios at both 1.5℃ and 2℃ of global warming, using a concept called “cooling degree days” to quantify exposure to uncomfortable temperatures. Cooling degree days help us assess when people will need to take extra measures, like switching the air-conditioning on, to keep themselves cool.

It calculates how much (in degrees), and for how long (in days), the outside average daily temperature exceeds a reference temperature – normally taken to be 18℃. For example, two days where the average outdoor temperature was 25℃ (7℃ above the 18℃ threshold) would have a total of 14 cooling degree days.

Northern Europe and Africa at risk

Our findings show that countries in the tropics will see the largest absolute increase in extreme heat as measured in this way if global temperatures rise from 1.5℃ to 2℃. Countries in central and sub-Saharan Africa, such as the Central African Republic, Burkina Faso, Mali, South Sudan, and Nigeria will be hit the hardest, with an additional 250 annual cooling degree days or more.

These repercussions of these results will impose further strain on the continent’s social and economic development. Our results are also a clear indication that Africa is shouldering the burden of a problem it did not create.

However, it’s the countries at northern latitudes that will face the greatest relative increase in uncomfortably hot days. Of the top ten countries with the most significant relative change in cooling degree days as global warming exceeds 1.5℃ and reaches 2℃, eight are located in northern Europe.

If we measured from today until we reached 2℃, this relative increase would be even higher.

Increasing heat exposure:

Fuelling global warming

Air conditioners are often seen as the go-to solution for rising temperatures, as they provide fast relief from the heat. However, if left unchecked, the increased demand for cooling to combat the heat will lead to higher emissions and further global warming.

This is not a hypothetical situation. In June 2023, as temperatures soared in the UK, the demand for air conditioning rose to such an extent that coal was burned to generate electricity.

Many air conditioners also use refrigerants called fluorinated gases. These gases can leak, and when they do they have a global warming potential up to nearly 14,800 times greater than CO₂.

The need for air conditioning can be reduced and even eliminated by making appropriate adaptations. These can be as simple as adding windows shutters or awnings, loft ventilation, painting your roof a light colour, enabling natural ventilation when the outside temperature drops, or using ceiling fans.

These would make it possible for people in northern Europe to stay comfortable during hotter temperatures without compromising the climate further for future generations. But this requires northern Europe to take the effects of climate change seriously and to start getting prepared for the coming heat.

Jesus Lizana receives funding from European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme.

Nicole Miranda and Radhika Khosla do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.