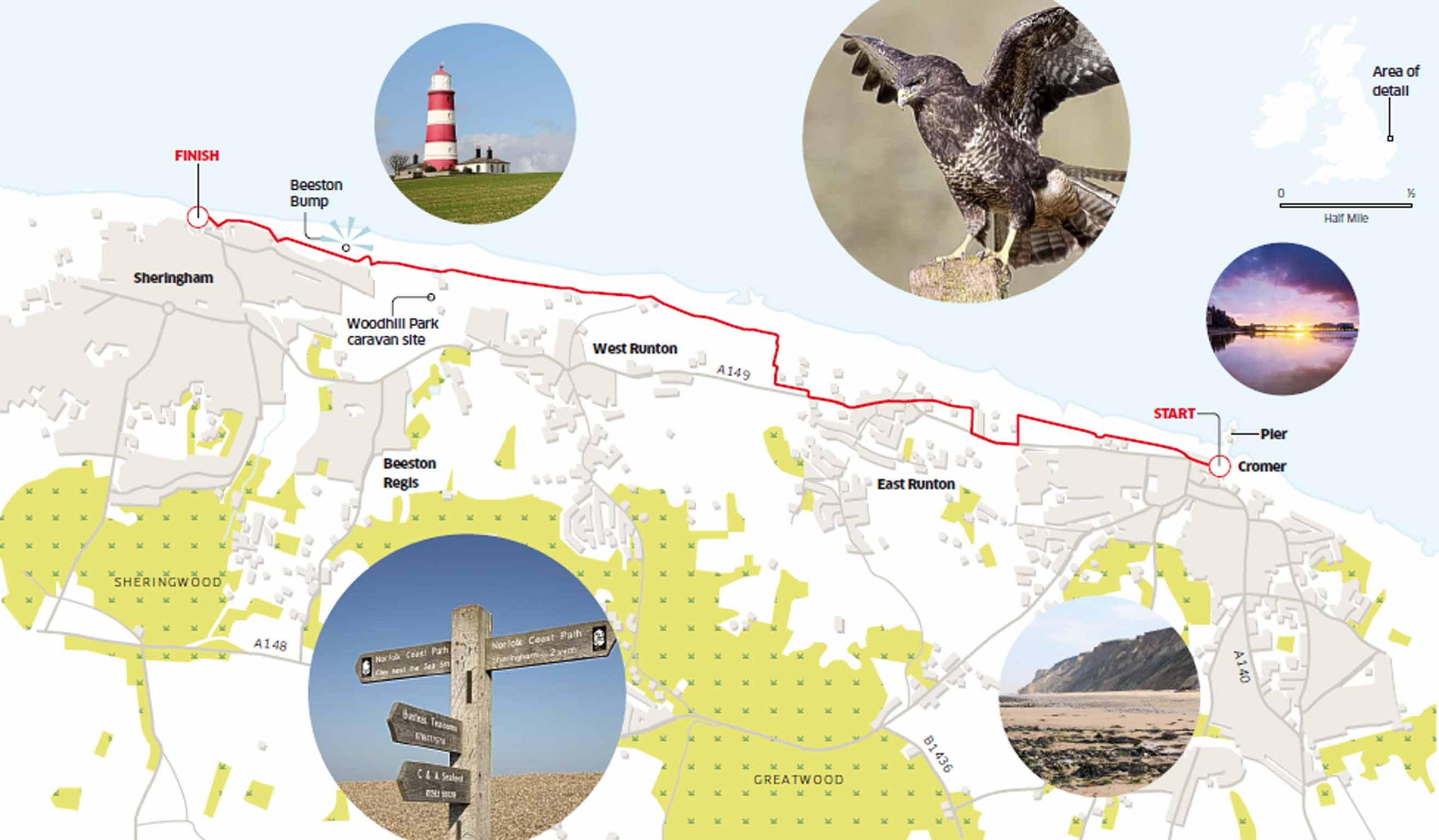

There's a charm to Cromer that lifts my spirits even before I start walking up the coast to Sheringham, its neighbour and rival for the seaside tourist shilling. Art galleries lie in wait, with their evocative seascapes, and the pier is one of England's loveliest. You're not charged for the privilege of setting foot on it, families are happily fishing and dropping lines for crabs, and at its far end, where it would have been easy to build an amusement arcade, there's a lifeboat station. From its railings I can see the undulating coastal path I'm to follow.

Before I reach the rural hinterland between the two towns though, I encounter the sobering spectacle of Cromer's battle with the elements. A year ago, Norfolk was hammered by storms; now formidable sea defences, designed to absorb another 50 years of sea level rises, are being put in place to keep the town safe. It's nothing new: the Domesday village of Shipden Juxta Mere lies sunken just off the Cromer coast, and the story goes that, on a still night, the bells of the submerged church can still be heard.

Soon, though, I'm out of town, following the coastal path just above the cliffs and around the back of allotments, briefly nipping into villages, but for the most part passing between the sea and civilisation.

The existence of this route is thanks to recent measures to resuscitate the England Coast Path, the long hoped-for route around the edge of the country. Up until mid-2013 – four years after the coastal corridor was announced – just 20 miles had been dedicated, and the dream looked set to be sacrificed on the altar of austerity and government apathy. Now, thanks to campaigns by the Ramblers, the National Trust and other groups, the pace, like a walker in a hurry for the last rural bus of the day, has quickened.

This autumn, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg announced the entire 3,000-mile route would be completed by 2020. The north-east Norfolk coast is one of the first sections to benefit, with new access agreements securing a route that now hugs the coastline, and no longer forces walkers on to kerb-free A-roads. Freshly minted fingerpost signs, the varnish still gleaming on the timber, accompany you.

The new route allows walkers to explore the coastline in more detail, and appreciate at first hand some of Norfolk's deep history, which dates back 900,000 years. My first stop after Cromer is the village of West Runton where the bones of a mammoth were exposed on the nearby beach after a storm in 1990. Excavations over the following five years unearthed 85 per cent of the skeleton, revealing it to be twice the size of modern African elephants and the biggest example of a steppe mammoth found anywhere in the world.

Just to the south of my route, at Happisburgh beach, the discovery of a Palaeolithic flint hand-axe dating back 555,000 years was followed by the oldest evidence of humans in northern Europe, including stone implements and 900,000-year-old human footprints – the oldest discovered outside Africa's Great Rift Valley. Most of these discoveries have generally been made by amateurs, so if you stare at your boots as you walk along, you may just come across something truly ancient.

At times the path is lined with salt-battered hedges; at other times old lobster pots have been stacked up and colonised by hawthorn, becoming hedgerows too. At Woodhill Park caravan site I pass a wildflower meadow, its flowers hunkered down for the winter, but covered with poppies, lady's bedstraw, and white campion. Come back at dusk, I was told, and you may catch a barn owl swooping low across these fields.

Beeston Bump, a large hillock that pops out of the gently undulating landscape, comes into view. To reach and climb it, I pass through gorse and, although just 63m high, Beeston Bump gives extraordinarily far-reaching views of its low-lying surroundings. Cromer is unexpectedly distant, and the summit is a good place to nail the myth that Norfolk is flat. Over the woodlands of Sheringham Park, which rise up to the west, I catch sight of a solitary buzzard. Closer by, a skylark flutters upwards with its signature jerky movements, which deep in winter could easily be mistaken for shivering.

My eye follows the route of the branch railway line from Norfolk to journey's end at Sheringham. I drop down the back of the hill and wander into Sheringham's back streets, a world of pebble-dash B&Bs that slowly gives way to stouter knapstone churches. There is no pier, but the seafront here faces west. The weather is in my favour, and the clear skies allow the dipping late-afternoon winter sun to sprinkle a few farewell flickers of gold on to the glassy sheen of The Wash.

DISTANCE: Four miles/7km

TIME: 2.5 hours

OS MAP: Explorer 252 Norfolk Coast East

DIRECTIONS The route is well way-marked and straightforward. Just follow the coastal fingerpost signs from Cromer.

STAYING THERE: Mark Rowe stayed at The Grove, in Cromer (01263 512412, thegrove cromer.co.uk), where a double room costs from £80. B&B.