As North Korea reignited international tensions in recent weeks with new rounds of missile tests, the hope generated by the summits between Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un has come into serious question.

Amid the ups and downs in the international community’s relationship with the North Korean regime, human rights activists have sought to remind the world that conditions remain grim for North Koreans.

For the past two decades, human rights organisations based in South Korea have worked with North Korean escapees to gather evidence on the scale and nature of the regime’s oppressive policies.

More recently, some organisations have begun applying new technologies to complement testimonies gathered through interviews. These include Geographic Information System (GIS) technology, which applies geographical analysis to detect patterns of state abuse not always apparent from interviews.

As the quality and availability of open source satellite imagery have increased, North Korea analysts have uncovered new information about the secretive state.

Executions and burials

The Transitional Justice Working Group (TJWG), a non-governmental organisation based in Seoul, South Korea, which investigates deaths of North Korean citizens in state custody, recently reported on a long-term project documenting North Korea’s human rights violations using GIS technology. Sarah was part of the small team of Korean and international researchers who wrote the report.

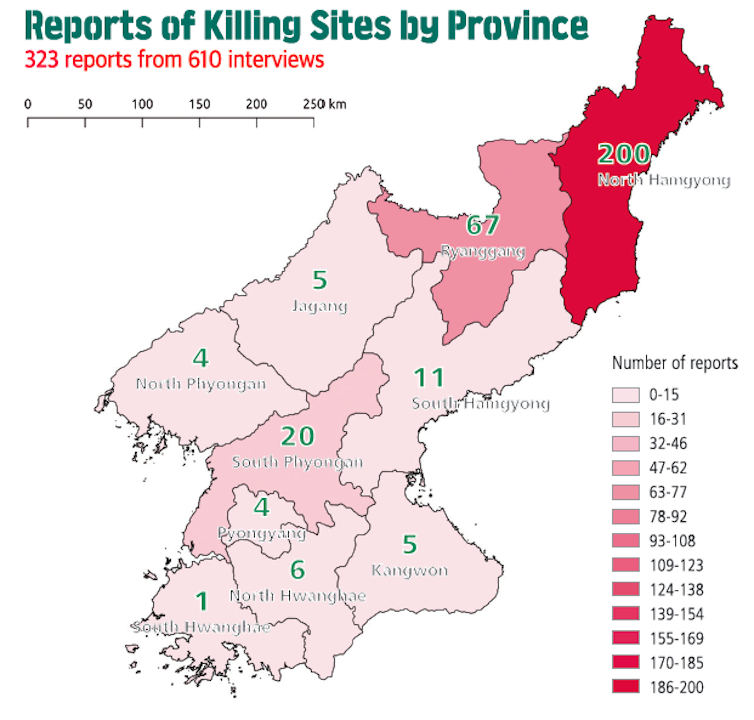

The project, which is ongoing, has so far gathered more than 300 reports of public execution sites – including hillsides, fields, markets and sports grounds. It has also gathered information on more than 25 sites where bodies have been disposed of by the state, by burial, cremation or other means. Public executions have been carried out for alleged offences including violent crime and watching illegally imported South Korean media. Yet the most commonly cited charges were related to property theft, such as stealing copper or livestock.

The researchers show North Korean escapees Google Earth satellite images of areas of the country where the escapees either lived or spent considerable periods of time. Focusing on images dating from around the time the reported events took place, where available, researchers then ask interviewees to point out the locations of any killing or body disposal sites of which they have knowledge.

These points are recorded along with the escapees’ narratives about the events associated with the sites, key details of which are put into a database. It then becomes possible to analyse the relationships of geographical coordinates to other variables, such as dates, associated criminal charges or proximity to certain government facilities. As the body of data grows, patterns in these relationships begin to emerge.

For example, the research shows that public executions have been clustered in many of the same spaces, such as a section of a city’s river bank, since the 1960s. The mountainous nature of North Korea, as well as the limited availability of fuel for transport suggests that officials from the Ministry of People’s Security may not travel far from a public execution ground to bury the dead and may reuse the same site repeatedly.

This process presents some challenges, including working with memories affected by the length of time since the events occurred, or confusion between events due to the sheer scale of abuses which have taken place over many decades in North Korea. Determining when a certain mass public execution occurred, for example, may be difficult when the interviewee can only recall that it was sometime in the early 1990s, when the weather was hot. But locating where such events happened on a map, and looking at multiple accounts related to the same site, can help researchers uncover common trends in state-sanctioned killings.

Building a case

The use of these technologies has not been without its critics, given the potential to misread the data, even by experts. Still, the high barriers to entering the country make satellite images an important source for outside observers of North Korea.

The hope is that satellite analysis will help future efforts to investigate and preserve certain sites as crimes scenes. Information gathered now can help trained forensic investigators work together with GIS analysts to more accurately locate the remains of victims, or where other evidence related to state-sanctioned killings and burials may be located. If North Korea becomes more open, it can also provide an understanding of the environment surrounding particular sites ahead of time, such as ease of access and potential costs of investigation.

This work is not without risks. There is no way to know whether the North Korean state may tamper with sites if it knows they have been identified, as happened in places such as Bosnia. As a result, for the time being, TJWG’s coordinates of sensitive sites such as killings and burials are not made public.

Any information gathered will need to be validated when access to North Korea becomes possible. There is always a risk of error because satellite images can vary in quality and the available data on North Korean infrastructure is far from complete.

The regime is concerned about the world finding out about its state-sanctioned killings. North Korean escapees told the researchers that in 2013 and 2014 local police used hand-held metal detectors to find and confiscate all mobile phones from the assembled crowd prior to an execution, to prevent anyone from recording the proceedings. If photo or video evidence were to get out, it could be possible to cross-reference it with satellite data as the BBC has done elsewhere, offering a more detailed picture of North Korea’s abuses to the international community.

Analysing data in more advanced ways can help human rights groups and the populations they serve get closer to the facts of abuses on the ground.

Sarah A. Son was employed by the Transitional Justice Working Group as part of the research team at the time this research was conducted and co-authored the project's latest report. She continues to support the project in a voluntary advisory capacity. The project was funded by the National Endowment for Democracy.

Markus Bell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.