It’s simple enough. One brother faces down another in one-on-one; the winner stays, the loser is replaced by another brother. It’s a more than 10-year-old tradition among the four Maye boys, raised by their parents in the hills of North Carolina, about 30 minutes north of Charlotte. The family’s gathering place wasn’t the kitchen, den or backyard, but instead a four-car concrete driveway with a drawn-on three-point arc encircling a stand-alone basketball hoop.

Just imagine big brother Luke, middle brothers Cole and Beau, and youngest brother Drake—most of them standing at six feet by middle school—knocking one another around on the pavement. Games were so intense that dad Mark supervised, half referee and half paramedic.

Once, Drake, a piñata to his older siblings, slammed head-first into the concrete, earning him stitches. To this day, he remains the baby of the group from more than one perspective. At 6'5", he’s the shortest of the lot. “He rides in the back of the car,” says Luke, laughing.

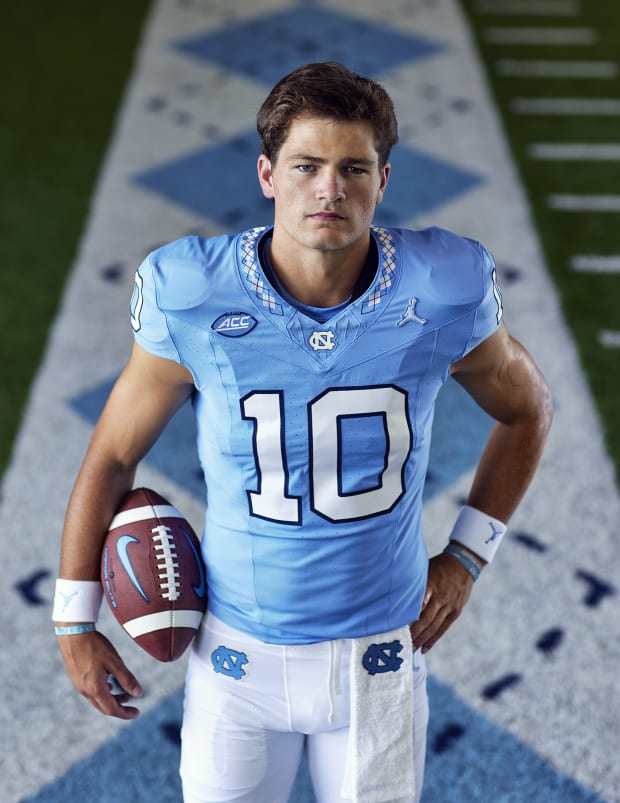

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

The good news is, basketball isn’t his game. In a matter of weeks last fall, Drake Maye, that once-little (littler, at least) bloody-faced kid, ascended to college football stardom. He won the Tar Heels’ starting quarterback competition 10 days before their season opener and then broke records on his way to becoming a Heisman Trophy contender. Previously known to Carolina fans more for his brother’s success—Luke played forward for UNC’s somewhat more noted men’s hoops program from 2015 to ’19—suddenly Drake became Chapel Hill’s big Maye on campus.

But in the family hierarchy, he remains last.

“I’m the runt,” Drake deadpans.

Drake and Beau, a junior walk-on for the UNC basketball team, share an apartment in Chapel Hill, and for a few weeks this summer they hosted Luke after he returned from a stint playing overseas (following a season in Italy and a couple in Spain, he just signed with Tofas, a Turkish League team). The trio restarted the family tradition but this time in Carolina’s hallowed gym, where Luke once starred. It was his game-winning jump shot against Kentucky that sent the 2017 Tar Heels to the Final Four and, eventually, the national championship.

But now his little brother is all the rage. A do-it-all dual-threat quarterback, Drake shattered the UNC single-season record for yards passing (4,321) and tied the school’s record for touchdown passes (38). He averaged more offensive yards in a game (358.5) than 36 teams in college football and became just the third quarterback in the last decade to average more than 300 yards passing while leading his team in rushing. The other two? Patrick Mahomes and Johnny Manziel.

He’s got Vince Young’s size (225 pounds) with similar speed. But his accuracy and decision-making? Well, they’re off the charts.

Like his brothers, he speaks in a deep country drawl that tends to unfurl in a hushed murmur and he has a dashing smile to go along with his dad’s bushy eyebrows. He’s a humble but fiery competitor who shoots bogey golf, has a filthy turnaround jumper on the hardwood and rarely loses on the pickleball court.

Watch college football with Fubo. Start your free trial today.

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

That competitive spirit tends to stay between the lines, though. In the new world of name, image and likeness (NIL), Drake has used his influence to arrange deals for his receivers and offensive linemen.

“He’s a special combination of everything good in our sport,” North Carolina coach Mack Brown says. Drake dispels any notion that he is some Mr. Perfect. Unprompted, he identifies his failures off the field (he consumes too many Cook Out milkshakes) and on it (he needs to improve his footwork and stop risking injury in the running game).

Despite that room for growth, Maye seems like the next big thing in college football, even if he’s around for just one more season. A redshirt sophomore who is eligible for the 2024 draft, Drake is projected as a top-10 pick by many prognosticators and, with a strong season, could find himself as the top quarterback in a loaded class at the position.

Still, he will forever be the Maye family runt—a runt who, this year unlike last season, will play with a target on his back and front.

“Every team is going to come after him,” says Luke. “That’s how I used to like it. They’ve got to get his best every game. That’s what Drake is starting to realize.”

Bob Donnan/USA TODAY Sports

Upon marrying Mark, a former North Carolina quarterback, Aimee Maye feared that he would be disappointed if they did not have a boy.

That quickly became a nonissue. Out came Luke, and then 15 months later came Cole, and then three years later Beau and a year later Drake. The mother of four boys born within six years, Aimee knows the maximum number of eggs she can scramble in her frying pan: 36. Often, even that wasn’t even enough.

“Sometimes I’d eat less so I didn’t have to make a second pot,” says Aimee, which is pronounced Aye-may, laughing.

The Mayes raised their boys to be polite, humble and, when involved in any kind of competition, kick everyone’s butt. They raised them on Carolina Blue as well. Aimee and Mark met at UNC in the 1990s. She was a recruiting host, and he was a graduate assistant under Brown during the coach’s first stint at the school. The only boy who veered from Chapel Hill was Cole, who has been forgiven for his heresy after helping Florida win the 2017 College World Series as a lefty pitcher.

The entire household, Aimee included, played sports. Her father started the first AAU basketball team in Charlotte, and she played hoops and golf until abandoning them for college life. Mark, a two-time All-ACC selection at quarterback, finished his career with 20 touchdown passes—or as many as his son threw in a six-game stretch last fall.

Aimee is 5'11", and Mark is 6'4". Naturally, they produced giants. Luke is 6'8", Cole 6'7", Beau 6'9" and Drake the, well, you know—rhymes with punt. But he’s fast. He’s the quickest of the bunch by far, Mark says. Luke is the best hoops player. Cole excelled in baseball, of course, and Beau towers over them all.

“Drake was a late bloomer,” Luke recalls. “He was shorter in all the family pictures, but he sprouted quickly.”

Drake began youth football as a linebacker and running back, but by junior high had moved to QB. He had plenty to toughen him up: When not outside on the court, the brothers were inside wrestling—and eating. There were lamps broken and “the normal holes in the wall,” says Mark. “Around the dinner table,” he says, “it sometimes felt like the locker room.” Fast-forward years later, and three of the four boys are back together in Chapel Hill. (Cole is in the real estate business in Charlotte.) At some point, Luke will head to Turkey to continue playing professionally. Last fall he stayed up late nights in Europe to watch little brother march into the North Carolina record books. Drake took Tar Heel Nation by storm after winning a tight quarterback battle with Jacolby Criswell, a highly prized recruit who transferred to Arkansas after losing the job (the two remain good friends and still FaceTime each other).

In a matter of weeks, Maye went from not knowing whether he’d start to becoming the first UNC quarterback to throw for five touchdowns in his debut, against Florida A&M. He threw for four more the next week, against Appalachian State.

Brown knew Drake was special long ago. He got a reminder last summer, when, in the heat of the QB competition, the coach left vacation to return to Chapel Hill and monitor workouts. He arrived on the field to see a quarterback—quarterback!—winning all the foot races with defensive backs and receivers.

“I told them, ‘You’ve got a QB outracing you,’ ” Brown recalls. “They said, ‘Coach, he’s got longer legs than we do!’ ”

Grant Halverson/Getty Images

Last fall Drake almost single-handedly won games on a team with a weak running attack and a sometimes atrocious defense. He became a local celebrity in this quaint college town. He’d walk across campus to giggling girls or chuckling boys, all of them whispering about his presence as he glided by. He made light of it: “Hey guys!” he’d yell. “What’s up?!”

Amid that stretch last fall, something else often happened as well—a bit awkward, especially for a guy with a girlfriend. “A lot of girls, they want me to sign the upper chest area,” Drake says, laughing. “I try to stay away from those.”

UNC started 9–1, its only loss to Notre Dame. And then things unraveled: A season-ending, four-game losing skid still stings. The Tar Heels blew a 17-point lead to a Georgia Tech team with an interim coach, lost in double overtime to NC State, dropped the ACC championship game to Clemson by 29 points and saw its defense wilt late in a one-point loss to Oregon in the Holiday Bowl. In those four games, Drake threw four touchdowns and three interceptions. One of his big brothers was there to offer, um, comfort.

“I gave him crap when they lost the last four games,” Luke says. “That’s how it goes.”

Having worked as a college coach for more than a decade, Chip Lindsey has been involved in at least eight job interviews. But he’d never been interviewed by a player—until last winter.

On Dec. 7, Phil Longo left his post as UNC offensive coordinator for the same gig at Wisconsin. Brown made the unusual decision to involve Maye in interviews during the search for Longo’s replacement. Separately, Brown and then Maye interviewed candidates. Then they came together to make the decision.

“Thank goodness, we came up with the same name,” Brown says. “If not, I might have been in trouble.”

Lindsey, a 48-year-old north Alabama native and former Troy head coach, brings with him a power-run, spread system developed, in part, from his stints under Gus Malzahn at Auburn and UCF. He doesn’t plan to make many changes to Maye and UNC’s air attack.

But the running game? Well, yeah. The Tar Heels were 67th in the FBS last season in rushing. In that 28–27 Holiday Bowl loss to Oregon, for instance, while Maye rushed for 45 yards, the rest of the team could muster only 71. The quarterback described UNC’s previous run scheme as “simple” and believes Lindsey will mix in a variety of formations and plays to enliven the unit. A more “downhill running” attack, Lindsey says.

Everyone knows things need to improve.

Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

“We have to run the ball better,” says starting center Corey Gaynor. “We’ve been working on it since January. We’ve got to take the stress off of his arm.”

Maye is the center of everything in Chapel Hill, and no one wants those around him to dash what is likely to be his last season in Tar Heel blue. Without the four-game skid, says Brown, “he would have been in New York [for the Heisman].”

It’s understandable. Improve the pieces around one of the country’s best quarterback talents, and you improve the team in general. But there is room for improvement from the QB himself, says Lindsey. Like Maye says, he needs to be smarter when he runs with the football. When Lindsey arrived, he created a film of about 15 plays last year in which Maye should not have run. “I saw too many highlights of him getting flipped,” says Lindsey.

Maye has another set of new eyes on him as well. Brown brought in Clyde Christensen as an offensive analyst this spring. He spent 27 years in the NFL, where he coached QBs like Tom Brady, Peyton Manning and Andrew Luck.

All of it is an effort to improve Maye and keep him happy while bettering the team. In the era of NIL and the transfer portal, such talented quarterbacks are prized possessions. They are sought after by the sport’s powerhouse programs.

Several schools at least showed interest in Maye during the offseason. Alabama? Georgia? Brown declined to name names. “I didn’t worry about [him leaving],” he says. “I worry more about our process in college football—that people shouldn’t be stealing people off people’s campuses. Drake came into my office unannounced and said, ‘Coach, you know I’m not leaving. I’m here to do this thing right.’ ”

Pitt coach Pat Narduzzi caused buzz this spring when he publicly suggested that teams were offering Maye $5 million to leave UNC. Even Brown, during a December interview, revealed that Maye turned down a “whole lot of money” to stay in Chapel Hill.

“Drake never entertained any of those,” Mark Maye says. “There wasn’t anything concrete. He never went into the portal. He never had a desire to go into the portal. He heard some about interest from one school or another. That’s all.”

Maye remained in Chapel Hill for a variety of reasons. Sure, there’s his close, historic connection to the program, his brothers, his teammates. But most of all, he believes he can help deliver North Carolina—and Brown—a national title.

Brown has a lingering desire to win a second championship trophy to pair with the one shimmering in a glass case in the office that his wife, Sally, an interior decorator, designed. Brown was at Texas when he won it, and a quarterback with a similar build and legendary legs—there’s that Vince Young comp again—clinched it for him with a win in one of college football’s all-time games, the 2006 Rose Bowl. But this runt he’s coaching now? Brown just hopes America gets to see that he might be even better.