The UK government and water companies have recently been heavily criticised for allowing raw sewage and other pollutants to spill into the nation’s waterways.

While a recent flurry of stories and reports could make this crisis feel very new to us, river pollution and concerns over it have a long history. This is something I have uncovered while doing a PhD focused on attitudes to water in England between 1550 and 1750, a period historians refer to as “early modern”. My research shows that, even in the era of Shakespeare’s “filth-clogged” Thames, river pollution was far from acceptable.

Precisely when the first river protection laws emerged in Britain is not clear, though we know that Roman law contained regulations with fines for polluting water, so early ideas may have been brought over through their occupation.

From as early as 1489, protections for rivers were starting to take on language that made clear that preservation was a chief concern. An act from the first years of Henry VII’s reign made the Thames and its protection the domain of the mayor of London as its “conservator”.

This usage in the context of the Thames represents, according to academics Keith Thomas and Bruce Boehrer, the first use of the idea of “conservation” in the English language in relation to protecting the natural world.

But this was far from a new idea. When challenged on his right to the river by later kings in the 1500s, the then mayor pointed out that “conservation and correction” of the Thames had fallen to city leaders since at least 1407.

Pollution of the river was a key concern, and this “conservation” was specifically defined in terms of preventing people from “annoying” the river by casting “any Soil, Dust, Rubbish, or other Filth into it.”

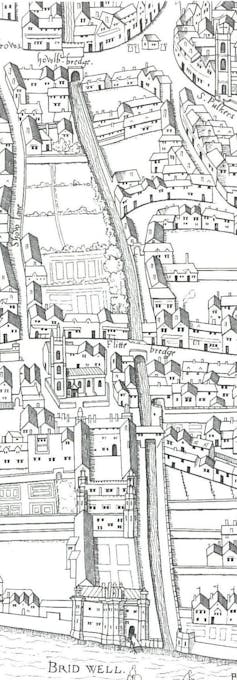

Despite these restrictions, Tudor London clearly did cast “other Filth” into its rivers. The Fleet river (left) was a “notorious” sewer by the 17th century, and as the map shows, it flowed directly into the Thames.

The author Ben Jonson, whose house was near the Fleet, took the state of the river as inspiration for his poem “On the Famous Voyage” which paints a nauseatingly vivid picture of the waterway’s condition through a mock voyage down it:

Your dainty Nostrils (in so hot a Season, When every Clerk eats Artichokes and Peason, Laxative Lettuce, and such windy Meat) Tempt such a passage? when each Privies Seat Is fill’d with Buttock? And the Walls do sweat Urine, and Plasters? When the Noise doth beat Upon your Ears, of Discords so unsweet?

Increasingly however, the state of rivers like the Thames came under criticism. Thomas Powell lamented the river’s treatment in a 1679 religious work, suggesting people treated God in a similar way to the river: poorly. “The Thames brings us in our Riches, our Gold, Silks, Spices: and we throw all our filth into the Thames”.

There were also specific health concerns. John Evelyn’s 1661 work Fumifugium criticised the polluted air in the capital. Part of the complaint was the damage that Evelyn claimed polluted air was doing to the water both in the city, and to those who lived downstream who he said emerged after bathing covered in a “web” of dust and grime.

Evelyn’s issues with the air highlight the importance of smell in early modern understandings of disease. If “corrupt” or “putrid” air was key to the spread of illness, the stench of the River Fleet was not only unpleasant – it was life threatening.

The threat of pollution therefore took two forms. There was the waste that ended up in the river, and the smell that resulted from it.

Both dangers appeared in those scenarios where authorities did step in and take action against polluters. In 1627, a case was brought by London residents against a house that made “allom”. Alum, as it is known today, was produced through the “boiling of urine” and the complaints were aimed at the “noisome stinking scum of a frothy substance” that it was dumping into the water.

Both the smell and contamination were claimed to have “cast many of [the nearby residents] into extremity of great sicknesses” and the building was shut down. Perhaps a more effective response than the UK manages today.

You might think that this was as bad as it could get, but a 1696 pamphlet suggested that the Thames was actually better off than most English rivers, which enjoyed fewer protections and in contrast were “choaked up with Filth”.

In a world without permanent sewage or waste disposal systems, it is perhaps unsurprising that some early modern rivers ended up in the state they did despite legal protections. But the reaction to their pollution shows us that, even in a time with limited alternatives, this scenario was not simply accepted without complaint.

Daniel Gettings does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.