Almost three years after a damning report into government procurement practices, it seems nothing has changed

It was déjà vu. Exactly 18 months ago, when Newsroom last took a good look at how the Government was spending the $51 billion of taxpayers money under its control, the IT sector was reeling from a decision to award a $38 million contract for an online Covid-19 vaccinations system to a consortium of multi-billion global giants including Salesforce, Amazon and Deloittes.

“It’s such a gross, ridiculous waste of money. I have never seen anything like it,” raged Ian McCrae, chief executive of Auckland-based health IT company Orion Health. It wasn’t just that he felt the same job could have been done cheaper at home. It was the lack of any proper, open procurement process.

"I strongly believe Covid was simply used to circumvent proper procurement and this has cost New Zealand hugely."

Victoria MacLennan, chief executive of the National Board of IT Professionals NZ, isn’t the leaping-out-of-her-chair-in-fury type. But her frustration is clear when she talks about the continuing lack of transparency around government spending decisions - in particular which ministries are buying from which companies and, more importantly, why they make the choices they do.

While the people in charge of improving procurement processes are pushing for openness, only a minuscule fraction of tenders are public, she says.

The IT sector estimates the government spends $2.6 billion a year on IT systems, MacLennan says. But in the year to June less than 3 percent of that spend ended up being tendered through government’s Marketplace platform, she says.

Three percent.

“The focus of the government has been to move expenditure to what they call the Marketplace, but only $77 million of that $2.6 billion total spend is going through the Marketplace. It’s tiny.”

It’s even worse when it comes to the Government Electronic Tender Service (GETS). When MacLennan teamed up with Laurence Miller of anti-corruption agency Transparency International and investigated GETS (“a free service designed to promote open, fair competition for New Zealand Government contract opportunities”, according to its website) they found just two percent of what government spent on IT contracts in 2020 was transparently awarded and notified.

This is unlikely to have changed much since 2020, says MacLennan, who has spent her career working in and with the New Zealand IT sector.

And this matters.

Lack of transparency means government departments often end up awarding the biggest IT contracts to international companies, with Kiwi firms having no idea why they missed out, which criteria the procurement team was using, and how to go about winning contracts in the future.

Waka Kotahi recently announced two big tenders, one for a $1.4 billion nationwide integrated [public transport] ticketing platform, one for a toll road management programme.

Both went to overseas companies.

Ignore the fact RNZ found the winning bidder in the ticketing system bid, San Diego-based Cubic Corporation, was “an American transport and military contractor that promotes its weapons-training systems by showing the targeting of men dressed in robes”, New Zealand has plenty of expertise in the technology space, MacLennan says.

“I find it hard to believe Waka Kotahi couldn’t have used at least some New Zealand companies in their solution, rather than awarding the entire tender offshore.”

Benefits for the local economy include boosting employment, increasing local expertise and potentially sparking export business.

“There’s no broader outcome criteria, no requirement for government agencies to think about creating jobs and stimulating business in New Zealand, and that’s disappointing,” MacLennan says.

Wellington-based (though more recently overseas-owned) ticketing systems company Snapper isn’t involved in developing the $1.4b one-stop ticketing system.

“The industry was surprised Waka Kotahi couldn’t find a solution where Snapper wasn’t either the entire solution or at least part of the solution,” MacLennan says.

Waka Kotahi spokesperson Andy Knackstedt says there was a robust and extensive procurement process and no New Zealand companies put in a proposal.

"Cubic will be building a team here to design, build and maintain the NZ ticketing solution," Knackstedt says. "All field engineering related activities are to be provided by a local sub-contractor to Cubic, and all financial services providers entities are also local subsidiaries."

‘No one wins from poor procurement’

In 2018, Infrastructure New Zealand, the Construction Strategy Group and Civil Contractors NZ commissioned consultancy company Entwine to look into industry concerns with public sector procurement of “fixed assets” - anything from buildings and roads to water pipes and electricity pylons.

The resulting report, Creating value through procurement, was hard-hitting.

Conversations with 25 leaders of public and private sector organisations found procurement practices confused ‘cheapest’ and ‘best value’, resulting in public funds being spent on sub-optimal products, report author Leah Singer wrote.

There was bureaucracy and “waste” in the procurement process, confusion around risk (which often led to financial losses on both sides), poor quality tender evaluation, lack of expertise in many government departments around public sector projects, and a culture of mistrust between the public and private sectors which “frustrates collaboration, prevents innovation and destroys value”.

“No one wins from poor procurement,” Singer said.

A year after the release of the Entwine report, the Government released new Construction Procurement Guidelines and updated its Government Procurement Rules.

“For a long time now, the focus has been on lowest cost,” Civil Contractors NZ chief executive Peter Silcock said at the time. “Agencies will now be required to change their procurement to focus on outcomes rather than cost, placing more emphasis on fair allocation of project risk to those best-placed to manage it.”

Three years down the track there’s little to indicate much has changed since 2018, or that suppliers are any happier with the way government spends tens of billions of dollars of taxpayer money.

Rather the reverse.

"There's no evidence of improvement," says Don Christie, co-founder of Catalyst IT. "There has been no fundamental shift in thinking or recognition that what Government calls a level playing field is actually skewed in favour of international companies. And there's no agency reporting on any impact of applying new broader rules and strategies."

"Our industry still feels acutely the effects of sub-optimal Government procurement," Priyani de Silva-Currie, Beca principal and president of the NZ branch of the Institute of Public Works Engineers Australasia, told Newsroom. "The findings of the Entwine Report are still apparent and visible today; the recommendations of this report hold true."

Often, she says, government procurement staff are too rushed to do a good job, and don't do the pre-tender planning needed to get the best outcome. Sometimes for a complex project they might not even provide the most basic information.

"You can't just say ' We are looking for innovation' or 'How we can transform the market'. They should at least articulate the outcome and the level of service they want to achieve. It's not an open cheque book on either side."

It's common for tender documents to be revised 5, 10, 20 or even 50 times during the process, as mistakes get rectified and clarifications added, de Silva-Currie says.

"It's a classic sign and we have a laugh about it. But it can be really costly."

A complex tender could tie up 20 people for three weeks and cost a company $100,000, she says.

"I don't think procurement people understand the effort and cost it takes to prepare a compliant and compelling offer of service to Government. If they don’t get it right and we have to go back and rework it, it makes planning really difficult."

A damning report

In May 2021, Newsroom wrote a story called Opaque, inefficient, unfair: Govt’s $42b procurement regime report card. The story looked at what was then the latest NZ Government Procurement Business Survey - companies supplying the government with goods and services giving their opinion of their procurement experience.

The survey revealed what appeared at the time to be a relatively shocking level of dissatisfaction with the Government as a customer.

The trouble is, the latest survey is worse - on pretty much every measure.

Asked about their initial engagement with Government, 24 percent of businesses rated their experience as poor or very poor, up from 22 percent in 2018. The number rating it good or very good fell slightly (from 41 percent to 40 percent).

Initial engagement with Government

Under “sufficiency of tender documents”, the number of positive responses fell from 59 percent to 53 percent between 2018 and 2021, and negative responses rose from 11 percent to 12 percent.

And in terms of ‘clarity of tender documents’, positives fell from 48 percent to 43 percent and negatives rose from 12 percent to 15 percent, although the result from a question about the overall quality of tender activity was a slight improvement from 2018.

Sufficiency of tender documents

The factors making it difficult for companies to effectively bid for government contracts in 2021 included ‘complicated procurement processes’ (25 percent), ‘lack of engagement and dialogue with government agencies’ (20 percent), ‘complex information’ (15 percent) and ‘lack of support from government agencies (14 percent).

Asked about whether companies were offered a follow-up debrief after bidding for a tender, as a way to learn from that experience and potentially win contracts in the future, 42 percent of respondents said ‘rarely’ or ‘never’ and only 28 percent said ‘always’ or ‘often’. Of those offered a follow-up meeting, 40 percent said they were often or always helpful, 28 percent that they were rarely or never helpful.

Broken down by sector, businesses in the construction sector were mid-range in terms of their evaluation of the Government’s overall quality of procurement. In construction, 34 percent were positive and 24 percent negative. In ICT, 26 percent were positive and 35 percent negative.

In ICT they were more critical - 26 percent were far from the most dissatisfied with the Government’s procurement performance, coming in at 34 percent and 26 percent positive, respectively.

The best and the worst job in the world

Laurence Pidcock is “the man trying to spend your $51 billion better” - the head of government procurement, tasked with a radical reform of the system.

When Newsroom spoke to him in December 2021, not so long after he started in the job, Pidcock had a newborn baby - his fourth child. People had told him he was crazy taking on such a tough role with a young family.

He said he knew, and took the job anyway.

How’s the year been?

"Procurement people are frustrated, suppliers are frustrated, ministers are frustrated.” Laurence Pidcock, NZ Government Procurement

“It’s been very hard - certainly as hard as I thought it would be. And it continues to be very hard. This is both the best job in the world and the worst job in the world.”

Getting people to be transparent about their tenders is hard - behavioural change is never easy. Attracting the right people is also hard, as is training them, encouraging innovation, and getting people to think about the broader outcomes that could see procurement become a game-changer for the economy and social issues.

On the positive side “my optimism comes from the fact everybody I talk to wants the same thing. Procurement people are frustrated, suppliers are frustrated, ministers are frustrated”.

Pidcock talks about 2030 as being a realistic timeframe for change.

“It’s so hard to get an entire profession to work in a different way.”

The next step, which should be ready by the end of the year, is an early stage dashboard bringing together already-existing information on spend, sector performance and procurement and making it widely available..

“It’s not going to give much better information on day zero, but it’s a good start and from there we’ll iterate and improve. It will be front and centre and easy for people to see, which will help from a behavioural change point of view because potentially you’ll be able to see by agency as well, so there’ll be some embarrassments from some agencies.”

It’s the people, stupid

By the middle of next year, Pidcock hopes to get some idea of which government agencies are performing well and which aren’t. Then after that, the goal will be making sure the individuals in those agencies have the skills and training to do the job.

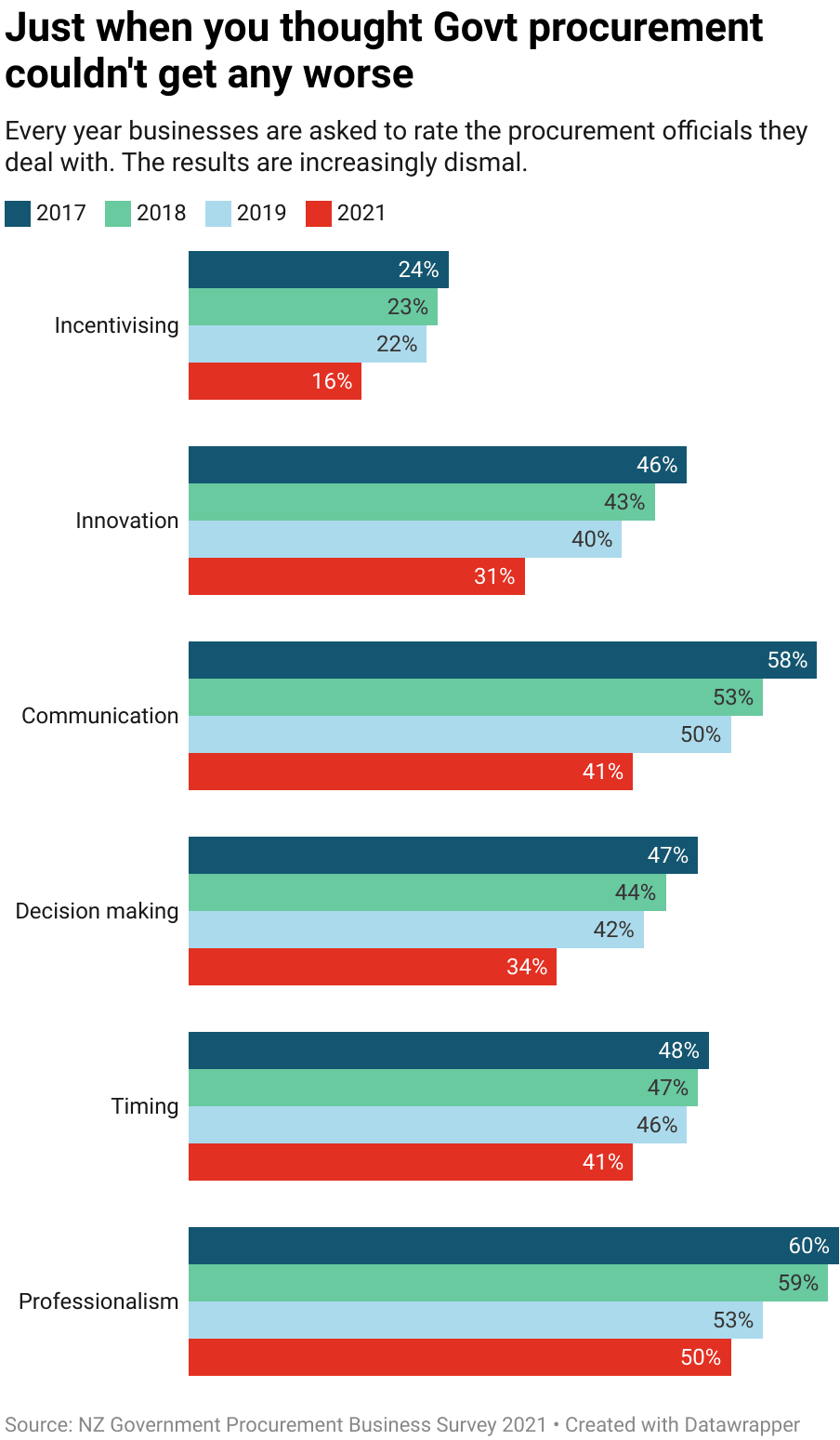

The NZ Government Procurement Business Survey - the poll where suppliers have their say - doesn’t examine the competency of individuals involved in the planning and tender stages of a procurement process. But it does asses the quality of the people who see a contract through the implementation phase.

In particular, the survey asks businesses to rate the competencies of these contract managers, and the results are shocking.

As the table above shows, positive ratings have dropped steadily - and in some cases significantly - over the past four years. In no category do contract managers get more than a 50 percent pass mark in the 2021 survey - and for skills such as innovation and decision making it’s considerably less.

Only half of businesses rate their contract manager as “professional”.

Asked what government agencies could do better, there were recurring themes.

“Treat suppliers with respect and work with them,” one said.

“Be more open and accommodating,” said another. “Relationships are valuable and should be the foundation of our engagement with government.”

“Be fair, transparent and give opportunities to others,” said a third.

“Be better prepared for the tender, with clear, realistic goals.”

“Suppliers complain about being asked the same questions over and over in tenders, and about client organisations with huge procurement teams spending months on irrelevant activities." Caroline Boot, Clever Buying

Caroline Boot has worked on both the supplier and client side of tendering processes since 1998 and now runs Clever Buying, a training provider for people working in procurement for government and local authorities.

What she says reinforces the findings of the business survey.

“We see people who don’t know how to plan a procurement process to deliver best value for money, who use a formulaic approach, or just recycle what’s been done in a previous procurement. They aren’t thinking what’s needed to differentiate a top quality supplier,” Boot says.

“Suppliers complain about being asked the same questions over and over in tenders, and about client organisations with huge procurement teams spending months during the tender process on irrelevant activities that won’t deliver the best solution.”

Many involved in procurement are thinking about broader outcomes on a theoretical level, she says, but don’t know how to fit non-financial outcomes - using local labour, lowering carbon emissions, or reducing waste into a tender process - at a practical level.

“And that means they aren’t achieving value for public money.”

So what is to be done? Laurence Pidcock says while senior leaders of government departments care about procurement, it’s not their primary concern.

“If I’m brutally honest, which I tend to be, my challenge is with the machinery of government, and how insignificant we are amongst all the other priorities.”

The thorny issue of incorporating broader outcomes into procurement is perhaps the most inspiring, but also the most challenging part of “procurement for the future” - the new government strategy. Choosing one set of outcomes over another is tough - and how do you measure social equity or sustainability or progress on Treaty of Waitangi issues?

New Zealand isn’t the only country where this change is fraught, Pidcock says.

“I went to an OECD meeting in Paris about a month ago, with all these heads of government procurement. And I was really excited - I thought I’d learn lots. But the one thing everybody was asking, and no one had a solution to, was how do we measure impact or broader outcomes in a consistent way.

“If I’m honest, nobody’s cracked it, and everyone’s got something different. And in New Zealand, we’ve got half a dozen different ways of doing it.”

He sees a future structure with a small number of overarching outcomes the government wants to achieve, and underneath that a larger number of specific measures. Potential suppliers will bid on which of those broader outcomes they can offer - and it will be the businesses which will deliver change, rather than government.

It’s tough but it could be revolutionary, Pidcock says.

“I can’t give up because I have this vision and I really want to see improvement, and I know we are making some progress. But it could be faster.”