It is difficult, in retrospect, to convey the impact that Eric Clapton had on the world of electric guitar playing in 1966.

For one thing, Clapton himself has spent most of his career since 1970 in denial about his achievements in revolutionizing the sound and status of the instrument, and he has been only too happy to let the spotlight fall instead on those who followed in his footsteps, including Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, and too many others to count.

But even allowing for Clapton’s latter-day reticence, it takes a supreme effort of either memory or imagination to fully appreciate how different the state and sound of electric guitar playing was prior to the release of John Mayall’s Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton in 1966.

The prototype guitar heroes of the Fifties and early Sixties were either moody types such as Link Wray and Duane Eddy, or bands like the Ventures and, in the U.K., the Shadows, whose guitar star was the clean-cut Hank Marvin.

What they shared was a guitar sound that seemed to have been recorded at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. Layers of echo and reverb were added to a precise plectrum and fingering style that placed the ability to conjure a haunting melody cloaked in a deep, twanging tone above all other considerations.

Clear enunciation of individual notes played cleanly in tandem with a deft tremolo bar technique was central to the sound of records ranging from Wray’s Rumble to any number of Shadows hits, from Apache to Man of Mystery.

As the new wave of beat groups got into their stride, particularly in the U.K., guitarists became emboldened and started to take a more unfettered approach, often informed by the stylings of the original American blues guitarists.

Brian Jones supplied a loud, super-aggressive slide guitar part to the front of the Rolling Stones’ I Wanna Be Your Man. Dave Davies offered a raw, runaway solo on the Kinks’ first hit, You Really Got Me. Pete Townshend introduced some startling feedback effects on the Who’s Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere. Jeff Beck layered experimental, Eastern-sounding, psychedelic solos across the Yardbirds hit Shapes of Things and its B-side, You’re a Better Man Than I.

But none of these early outliers had truly captured what a full-blown, modern electric guitar sound could be – or was about to become.

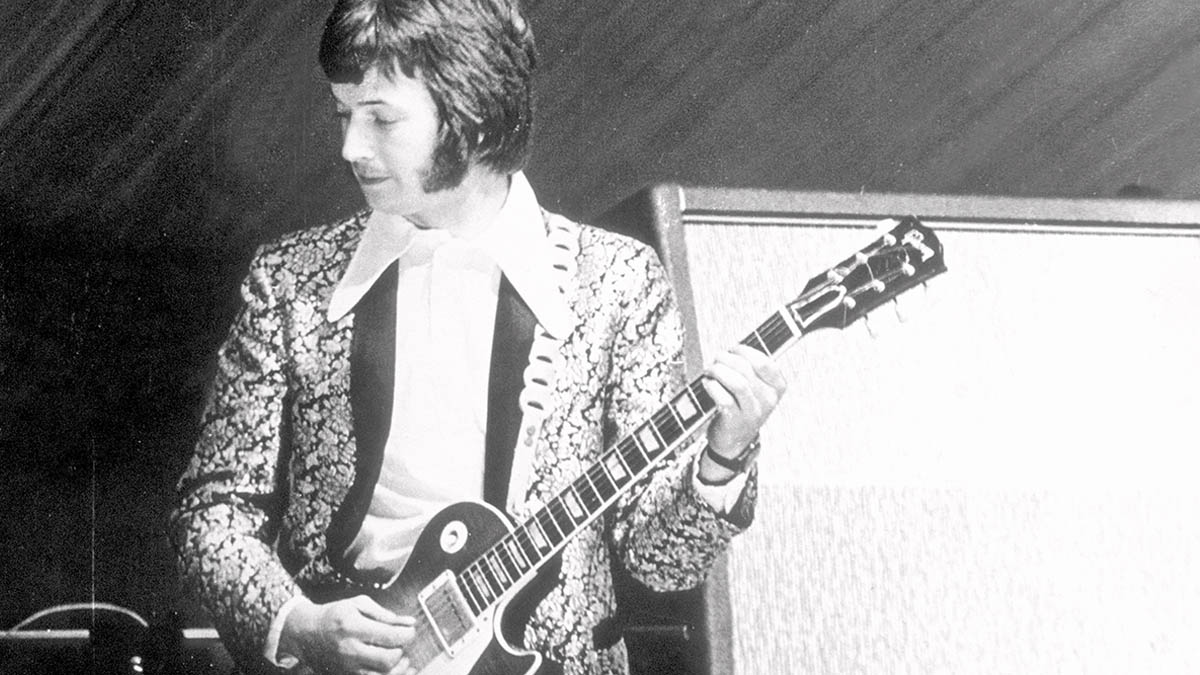

Clapton, meanwhile, had been not-so-quietly working up to his piece de resistance for some time. As the guitarist in the Yardbirds from 1963 to 1965, he gained a cult following that was out of proportion to the traditional status of a non-frontman musician in a band. This was thanks in part to his cool fashion sense and stage presence, but in even larger part to his incendiary soloing skills. The band’s debut album, Five Live Yardbirds, released in the U.K. in December 1964, was both a blueprint and a harbinger of what was to come.

A raw, scrappy, low-budget production, Five Live Yardbirds was recorded without fuss or fanfare at one of the band’s regular shows at the Marquee Club in London on March 20, 1964.

It was notable for many things; the incredible energy of the performance was evident from the opening surge of Chuck Berry’s Too Much Monkey Business, in which Clapton and bass player Paul Samwell-Smith engage in a whirling, skirling, insanely propulsive blast of soloing that had a foretaste of the punk aesthetic about it.

Clapton’s developing skill as a soloist was clearly on display throughout numbers such as Eddie Boyd’s slow blues Five Long Years and a rip-roaring take on John Lee Hooker’s Louise.

The recording also captured several extended improvised passages – what the band referred to as their “rave-ups” – in songs such as Howlin’ Wolf’s Smokestack Lightning and a ragged version of Bo Diddley’s call-and-response epic Here ’Tis, in which Samwell-Smith and Clapton performed a high-speed duel amid a closing sequence of indistinct aural mayhem from band and audience alike.

These rave-ups were quite unlike anything that any other “pop” or beat bands of the pre-rock era had committed to tape and were a precursor of the working practices that Clapton would later pursue with monumental results in Cream.

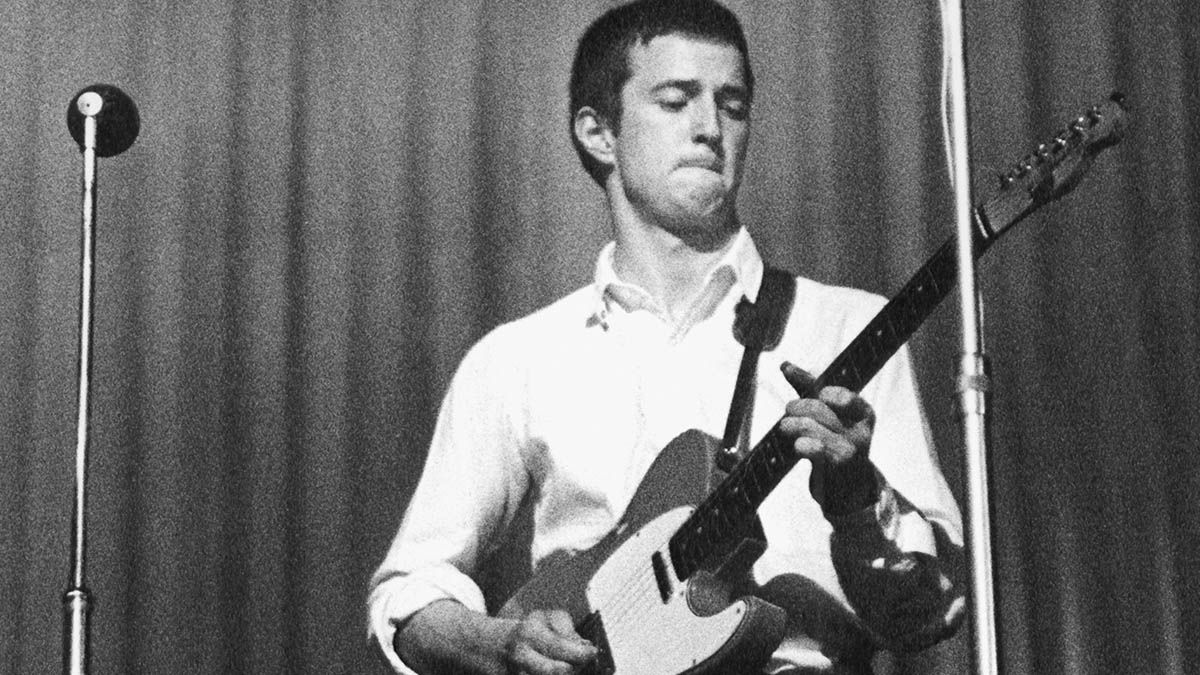

What Five Live Yardbirds did not possess was anything remotely resembling a modern lead guitar sound. Throughout his tenure with the Yardbirds, Clapton mostly played a red Fender Telecaster through a Vox AC30. The sound this produced, although perfectly acceptable for the period, was comparatively thin and trebly with virtually no sustain.

Clapton continued to use the Telecaster when he initially joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers in April 1965. But the following month he bought a sunburst 1960 Gibson Les Paul Standard with humbucking pickups, which turned out to be a game-changer.

This instrument, which became known as “the Beano Burst” after the nickname of the album he recorded with the Bluesbreakers the following year (Clapton is reading a Beano comic in the cover photo), has acquired a mythical status in the guitar world – not least because it was stolen soon after Clapton joined Cream in 1966 and has since vanished into a swirling mist of rumors as to its whereabouts, rumors that continue to surface to this day.

“The Les Paul has two pickups, one at the end of the neck, giving the guitar a kind of round jazz sound, and the other next to the bridge giving you the treble,” Clapton explained in his 2007 autobiography. “What I would do was use the bridge pickup with all of the bass turned up, so the sound was very thick and on the edge of distortion.

I also used amps that would overload. I would have the amp on full and I would have the volume on the guitar also turned up full, so everything was on full volume and overloading

Eric Clapton

“I also used amps that would overload. I would have the amp on full and I would have the volume on the guitar also turned up full, so everything was on full volume and overloading. I would hit a note, hold it and give it some vibrato with my fingers until it sustained and then the distortion would turn into feedback. It was all of these things, plus the distortion, that created what I suppose you could call ‘my sound.’”

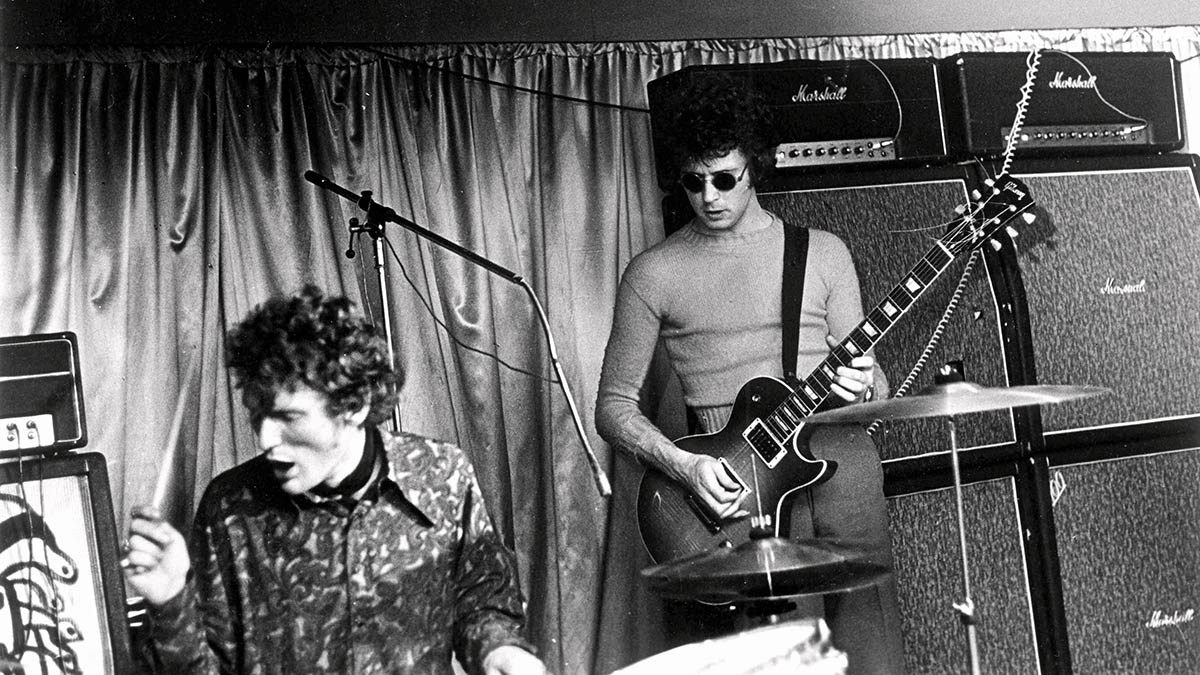

While the heavy, humbucking resonance of the Les Paul was key to the overall sound, so too was the new Marshall amplification that Clapton also bought into at this time. A small, innovative business run by Jim Marshall, an ex-drummer, the company was at that time based in Hanwell, West London, from where Clapton acquired a Marshall model 1962 2x12 combo based on the JTM45 design.

This new setup produced a much fuller, more powerful sound than his Tele-and-Vox combo, and even before the release of the Beano album, it was clear something special was in the air.

Mayall’s Bluesbreakers didn’t tour, exactly; they simply played six or seven nights a week as a matter of course. “We were paid £35 a week,” Clapton recalled. “It was a set wage no matter how much work you did. The idea was that you would play a gig, and when you were done you might have to play again that night.

A not un-typical night might involve traveling up to Sheffield to play the evening gig at eight o’clock, then heading off to Manchester to play the all-nighter, followed by driving back to London and being dropped off at Charing Cross station at six in the morning.”

It is not altogether clear when the graffiti proclaiming that “Clapton is God” started to appear on the streets of London. But the equipment overhaul and the intense gigging schedule had clearly elevated the guitarist into an exalted zone as a performer.

There is a live recording of the Bluesbreakers playing Call It Stormy Monday at the Flamingo Club on March 17, 1966 – two weeks before Clapton’s 21st birthday and a month before the Beano album was recorded – that has been hailed by several commentators as one of the best blues guitar solos ever.

Clapton’s tone, along with the outrageous timing and aggressive phrasing on this recording, is little short of supernatural. Nashville guitar great Kenny Vaughan [Marty Stuart & His Fabulous Superlatives] spoke for many when he called it “just the most wicked-ass… frantic, most intense guitar solo you ever heard on a blues in your life.”

It sounds phenomenal in every department – even today. But imagine how it must have sounded to the guy who had just wandered into the bohemian neighborhood of nightclubs, strip joints and coffee bars on Wardour Street in 1966 and happened to hear that solo. It must have been like hearing music from another planet.

Against the odds, the Beano album caught something of the thrill of that moment in time, making it one of the most successful exercises in the art of capturing lightning in a bottle yet undertaken in the modern recording era.

“We went into the Decca studios in West Hampstead for three days in April [1966] and played exactly the set we did on stage, with the addition of a horn section on some of the tracks,” Clapton said. “Because the album was recorded so quickly, it had a raw, edgy quality about it which made it special. It was almost like a live performance.

“I insisted on having the mic exactly where I wanted it to be during the recording, which was not too close to my amplifier, so that I could play through it and get the same sound as I had on stage.”

That was all very well for Clapton. But for producer Mike Vernon and engineer Gus Dudgeon, it wasn’t quite that simple, as Mayall recounted in his 2019 autobiography.

“I recall that the engineer, Gus Dudgeon, was horrified that Eric was intending to play through his Marshall amp at full volume,” Mayall said. “This simply wasn’t the acceptable way to do things in 1966. However, Eric stood his ground, refusing to turn his amp down. Mike Vernon had to mediate in order for us to start.”

“It took a while to get a sound that everybody was happy with, especially Eric, but everybody had to take on board that we were going into an unknown era,” Vernon told Harry Shapiro in 2011.

“Nobody in Decca studios had ever witnessed somebody coming into the studio, setting up their guitar and amp and playing at that volume. People in the canteen behind the studio were complaining about the noise. Normally they’d never hear it, but this was travelling around the studio complex. People were saying, ‘What the bloody hell is that?!’ and coming to see what was going on.”

The resulting album – Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton by John Mayall – marked Year Zero for the modern electric guitar sound. Clapton’s tone was nothing short of revolutionary and, harnessed to the skill and visceral emotional quality of his solos (especially on slow numbers Have You Heard and Double Crossing Time), produced an effect of a different magnitude to anything that had gone before.

Kudos to Mayall for assembling a great collection of new and traditional blues songs and stamping his singular English mark on them. And respect to the fine rhythm section of John McVie (bass) and Hughie Flint (drums). But this album was all about Clapton using his Gibson/Marshall setup to redefine the sonic and technical norms of electric guitar playing.

Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton ushered in a new era, not just in the playing of music but also the marketing of it. It was released July 22, 1966, with little fanfare, and promptly rose to Number 6 in the U.K. albums chart.

This was unheard of for an act that had enjoyed no previous success in the singles chart, and its unexpected yet emphatic progress was a key moment in the process whereby albums started to take over from singles as the barometer of a band’s success.

When we heard the Beano album, that was like… Nobody had ever heard a guitar sound like that

Kenny Vaughan

With its revolutionary guitar sound and compelling spiritual vigor derived from the musicians’ deep love and knowledge of American blues forms, the impact of the album was seismic on many levels. A generation of guitarists received the wake-up call of their careers, and within a year the British Blues Boom would be in full swing. More than that, it was effectively the first “rock” album.

“When we heard the Beano album, that was like… Nobody had ever heard a guitar sound like that,” Kenny Vaughan said. “Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson records from the 1950s had some wicked-ass sounds. And, of course, Guitar Slim and Earl King – they both had great sounds. And Link Wray had a brash, rude sound. But they weren’t like that. Nobody had that Eric Clapton sound on that record.”

Nobody had it – and now everybody wanted it. Unfortunately for Mayall, by the time the Beano album was released, Clapton had already left the group. Ever the pragmatist, Mayall immediately recruited Peter Green to replace him and continued his eight-days-a-week schedule playing to ever-expanding audiences.

Clapton, meanwhile, had embarked on another project that would further define the role of the modern guitar hero and redraw the boundaries of the rock genre he had already done so much to invent.

Cream were the first power/guitar trio and the first group of any kind to bring a flamboyantly virtuoso musical technique to bear on the traditionally basic structures of popular music. Drummer Ginger Baker and bass player/vocalist/harmonica man Jack Bruce were highly evolved musicians with backgrounds in jazz, where the impulse to experiment and improvise at length was taken as part of the basic motivation for performing.

To play with musicians like these gave Clapton an opportunity to deploy his technique to its full extent and explore musical avenues that took him far beyond the confines of performing in a regular band.

Cream were a short-lived and volatile combination of individuals, but it’s worth remembering the spirit of optimism that brought the group together. “Musically we are idealistic,” Clapton told Penny Valentine in July 1967. “When I first met Ginger and Jack I realized they were the only two musicians I could ever play with.”

When I first met Ginger and Jack I realized they were the only two musicians I could ever play with

Eric Clapton

Cream played their first gig at the Twisted Wheel in Manchester on July 29, 1966, the night before England won the World Cup, and the trio’s first album, Fresh Cream, was released just five months later on December 9.

The chronology of the 1960s gets a bit hazy after all this time, but it is worth noting that Jimi Hendrix released his first single, Hey Joe, one week after Fresh Cream.

Indeed, when Hendrix’s manager, Chas Chandler, was trying to persuade Hendrix to move from New York to London, one of Chandler’s key bargaining chips was to promise that once they were in London, he would arrange for Hendrix to see his hero, Eric Clapton, playing with Cream. It was perhaps no coincidence that Hendrix also elected to form a trio as opposed to a conventional four-man band on his arrival in London.

With Fresh Cream, Clapton further extended the range of sounds and musical sensibilities available to the modern guitar hero. On Sweet Wine, he constructed a latticework of interlocking guitar lines – some of them little more than wails of feedback, others hauntingly melodic – to create a passage that was more of a soundscape than a guitar solo.

He developed an extraordinary sense of narrative in his solos – which even on the extemporized blues rumble of Spoonful or the two-chord chant of I’m So Glad seemed to hang together as if they were totally spontaneous and carefully structured at the same time.

As they toured America, the trio’s facility for improvising around a commonly understood framework became ever more finely developed. They played many times at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, where promoter Bill Graham gave them carte blanche to play for as long and as loud as they liked, even if the show went on until dawn the next day.

“It was very liberating,” Clapton recalled. “We’d go off in our own directions, but sometimes we would hit these coincidental points… and we would jam on it for a little while and then go back into our own thing. I had never experienced anything like it. It was nothing to do with lyrics or ideas; it was much deeper, something purely musical. We were at our peak during that period.”

This semi-improvised approach led to one of the most celebrated guitar solos of all time, in the shape of the comparatively concise and structured live version of Crossroads recorded on March 10, 1968, on a mobile studio parked outside the group’s gig at the 5,400-capacity Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, and first presented to the wider world as the opening track on the live disc of the double-album Wheels of Fire, released on August 9 of that year in the U.K. (June 14 in the U.S.).

Clapton’s phrasing, timing and choice of notes on this version was sensational, as he started in a low register and gradually climbed over two verses building tension and excitement. After another verse of vocals, he came back in for a second stretch of solos, doubling the intensity in all departments for another three verses.

Never repeating himself or losing his way through the intense three-way wrestling match going on between the guitar, bass and drums, he pulled out a succession of soaring blues licks and double-stop bends to create a thrilling climax that was both super-aggressive and intensely focused. In the many polls, lists and tabulations of Clapton’s greatest guitar solos, this is the one that invariably comes out at the top.

Surprisingly, by modern standards, all the sound of the guitar (and the bass, for that matter) at Cream’s shows was generated from the back line. None of the speakers for the instruments were miked up and put through the PA, even in venues of 5,000 capacity or more.

The PA systems of the time were still unbelievably rudimentary; a couple of WEM columns or a Marshall 200-watt system for the vocal mics and maybe a couple of overhead mics for the drums was considered sufficient for a gig at the Royal Albert Hall in London.

The incredible sound that Clapton got with Cream (as with Mayall before that) was a function of the outrageous volume at which he played his Gibsons, which were usually either the 1964 SG Standard affectionately known as “The Fool,” a ’63/’65 one-pickup Firebird 1 or a ’64 ES-335.

He generally used two 100-watt Marshall stacks, each comprising a model 1959 100-watt head, a model 1960 angled 4x12 cabinet and a model 1960B flat-fronted 4x12 cabinet.

“I set them full on everything,” Clapton told Rolling Stone in 1967. “Full treble, full bass and full presence, same with the controls on the guitar. If you’ve got the amp and guitar full, there is so much volume that you can get it 100 miles away and it’s going to feedback – the sustaining effect – and anywhere in the vicinity it’s going to feedback.”

Clapton gradually introduced various pedals into his setup. He was the first “name” guitarist to release a track featuring a wah pedal – the Vox V846 (later reissued as the Clyde McCoy) – which he used on Tales of Brave Ulysses, released as a U.K. B-side to Strange Brew in June 1967.

Although Hendrix ultimately made much more extensive use of the wah and did far more to popularize it, his first use of the pedal wasn’t heard on record until Burning of the Midnight Lamp, a U.K. single released in August 1967.

Clapton also used a Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face, notably to beef up the iconic riff of Sunshine of Your Love and to add extra saturation and sustain to his sound on White Room and others.

He used other pedals and effects – including the revolving (Leslie) speaker sound heard on Badge – but often his amp and guitar settings, combined with his extraordinary touch, were all it took to generate a specific sound, such as the high, pure “woman” tone he conjured on Outside Woman Blues and others.

The huge popularity and acclaim that greeted Clapton and Cream inspired a transformation in popular music on many levels. The sheer volume at which they played and the heavy, riff-based style of songwriting they developed paved the way for Black Sabbath and Deep Purple – both founded in 1968 – and the subsequent birth of heavy metal.

And Cream’s fondness for improvising unleashed a tsunami of extended jamming among the heroes of the heavy rock genre they had done so much to create. It’s hardly an exaggeration to say that by their example Cream transformed a concert and record industry previously dominated by the three- or four-minute song structure into a world where long-form improvisation and instrumental free-for-alls became commonplace, if not the norm.

Hendrix certainly took it as the model for his live performances, as did Led Zeppelin – who, of course, started life as the New Yardbirds and thereby carried forward the legacy of the original Clapton rave-ups that got the ball rolling in the first place. And over the next few years, bands such as Ten Years After (at Woodstock), Mountain, Humble Pie and many others piled in with ever more extravagant performances that trod an increasingly erratic line between grand musical visions and wanton grandiloquence.

In 1968 Canned Heat filled two sides of their double-album Living the Blues with one track, Refried Boogie, a 40-minute epic of non-stop noodling and nebulosity.

It all got to be a bit too much for Clapton. He was particularly affected by a negative review of a Cream show in Rolling Stone by Jon Landau, who described the band as “three virtuosos romping through their bag… always in a one-dimensional style” and Clapton as “a master of the blues clichés of all of the post-World War II blues guitarists.”

“And it was true!” Clapton said later. “The ring of truth just knocked me backward.”

By that point, Clapton had been performing for many years at a level of intensity that had become impossible to maintain. There was an emotional cost to digging so deep into his reserves of musical creativity night after night, not to mention the physical toll of doing so at such punishingly high volumes.

“When you’re in your mid-20s you’ve got something that you lose,” Clapton reflected in an interview with Q magazine in 1986. “If I was a sportsman I would have retired by now. You’ve just got a certain amount of dynamism that you lose when you turn 30. You have to accept that otherwise you’re chasing a dream.”

If I was a sportsman I would have retired by now. You’ve just got a certain amount of dynamism that you lose when you turn 30. You have to accept that otherwise you’re chasing a dream

Eric Clapton

Looking back on that period much later, he recalled that, “There were times too when, playing to audiences who were only too happy to worship us, complacency set in. I began to be quite ashamed of being in Cream, because I thought it was a con. Musically I was fed up with the virtuoso thing. Our gigs had become nothing more than an excuse for us to show off as individuals, and any sense of unity we might have had when we started out seemed to have gone out of the window.”

Clapton made one last roll of the guitar hero dice with the ill-fated supergroup Blind Faith, which came into being, recorded and released a U.S. and U.K. chart-topping album, headlined a massive show in Hyde Park, toured in Scandinavia and America and then split up – all between January and August 1969.

“I think just playing the guitar isn’t enough,” Clapton told Rolling Stone the following year. “If I was a great songwriter or a great singer, then I wouldn’t be so humble about it. I wouldn’t be shy.”

So saying, Clapton very firmly stepped down from the pedestal onto which he had been placed and turned his back on the world of rock virtuoso superstars he had been instrumental in creating.

He (along with George Harrison) instead joined forces with Delaney & Bonnie Bramlett, a husband-and-wife duo from Los Angeles whose loose-knit band had supported Blind Faith on their tour of America. Delaney & Bonnie’s soulful blend of Southern rock, blues and gospel music was a soothing balm to Clapton’s troubled spirit.

“You really have to start singing, and you ought to be leading your own band,” Delaney told Clapton. “God has given you this gift, and if you don’t use it he will take it away.”

Clapton took Delaney’s advice to heart, and his subsequent campaign since the 1970s to reinvent himself has been so successful that as far as many casual observers of the rock world today are concerned, he is now regarded as a singer who also plays a bit of guitar.

And yet the influence that Clapton had, whether directly or indirectly, on just about every electric guitarist who followed him is undeniable. Just listen to Mick Taylor playing Snowy Wood on the Bluesbreakers’ 1967 album Crusade. Or check out the incredible off-the-cuff recording of Eddie Van Halen conjuring a note-perfect recreation of Clapton’s solo from Crossroads during a 1984 radio show called The Inside Track.

Then there’s John Mayer’s emotionally charged playing (and soulful singing) on Gravity. Mayer once described Eric Clapton as his “musical father” and has often performed Crossroads in his live shows, while many latter-day guitarists ranging from Joe Bonamassa to Gary Clark Jr. have testified to Clapton’s towering influence on their playing.

“Cream explored the outer reaches that three players could accomplish,” said Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top, another trio that emerged from under the long shadow of Clapton, Bruce, and Baker. Gibbons nominated Fresh Cream as one of the albums that changed his life, no less, delivering his verdict on the group’s sound with a typical Texas flourish: “Killer tones.”

- With thanks to Geoff Peel, London.