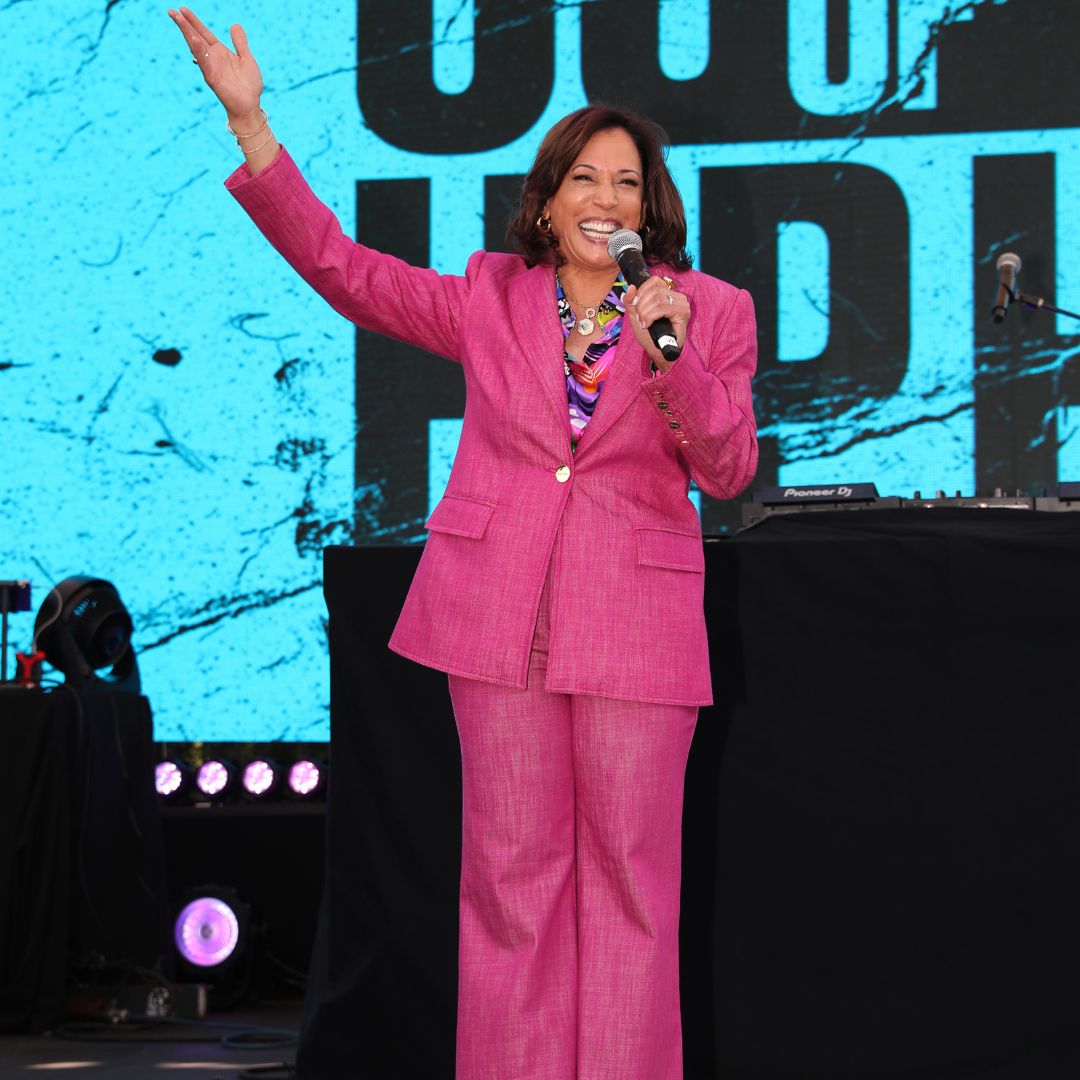

Kamala Harris officially started running for President of the United States less than two weeks ago, but her identity is already being questioned by Trump. Speaking at the National Association of Black Journalists panel earlier this week, he accused Harris of ‘turning on’ her Blackness. It’s just the latest example of multiracial identity being maligned and misunderstood, and it shows that we still have a long way to go before mixed people are allowed to define themselves with multiplicity.

“She was always of Indian heritage and she was only promoting Indian heritage. I didn’t know she was Black until a number of years ago when she happened to turn Black, and now she wants to be known as Black.” This is what Donald Trump said at Wednesday’s National Association of Black Journalists panel, where three Black female news reporters grilled the ex-US president on his term in the White House, current campaign for re-election and Democratic opponent, Kamala Harris.

Born to a Jamaican father and a Tamil Indian mother, Harris is among 33.8 million multiracial people in America. Her experience is one of duality, having grown up influenced by both sides of her heritage. She has referred to herself as Indian and as Black, as is her right, so why are people telling her that she’s wrong?

Trump isn’t the first to raise questions about Harris’s Blackness – commentary on social media, including from Black Americans, has argued that Harris isn’t Black because her policies don’t uplift Black people.

How mixed people are seen is rarely up to us

Isabella Silvers

The Vice President’s decisions haven’t always sat neatly on the political left or right – Harris has been accused of supporting policies that disproportionately affected Black citizens, like a push for jail time for parents of truant children, but then implemented a programme to rehabilitate, rather than incarcerate, nonviolent offenders. She has spoken out against police brutality but has been criticised for failing to charge officers said to have used excessive force.

Harris has also been targeted for not being African American. Her mother, Shyamala Gopalan, moved to the US from Chennai, while Harris’s father, Donald J. Harris, arrived from Jamaica in the Caribbean. Trump, never one to back down, has also posted a clip of Harris referring to herself as Indian, captioned, “Crazy Kamala is saying she’s Indian, not Black. This is a big deal. Stone cold phony.”

But none of this means she isn’t Black. Being Black or South Asian isn’t a political state of mind – just look at our own Conservative government, who upheld maddening immigration rhetorics that would have seen their own families, and mine, turned back at the border. It seems that unlike monoracial politicians Rishi Sunak, Kemi Badenoch, and Suella Braverman, Harris’s identity can be questioned because there’s another ‘side’ to push her into.

Unfortunately for critics, race doesn’t work like that. We’re often judged by appearances without curiosity about what might lie beneath, meaning that, for many, one look at Kamala’s darker skin will immediately set her apart. Her lighter complexion undoubtedly gives her benefits not afforded to darker-skinned Black women, but her shade won’t go unnoticed, and how she’s received in the world will reflect that.

It’s all well and good telling the presidential candidate to “claim Indian” instead (as one TikTok user did,) but it’s really not up to her. Harris has said as much herself, sharing how her mother raised her and her sister as Black within their South Asian household, knowing how they’d be seen in the world. These experiences are important, and no part of her heritage should be erased.

There are no boxes you have to tick in order to be Black apart from being Black

Nicole Ocran

Nicole Ocran, co-host of the Mixed Up podcast and co-author of The Half Of It, who has a Ghanaian father and Filipino mother, recalls, “Growing up in the US, I was always seen as a Black girl,”. “Even now, I’m outwardly viewed as a Black woman first and never as an Asian one. That’s something I am still proud of and have grown to accept, even when I wish recognition of my Filipino heritage was more forthcoming.”

“There are no boxes you have to tick in order to be Black apart from being Black,” she adds. “It doesn’t matter if you went to a historically Black college or not, what your politics are… There is nothing about Harris’s mixed identity that is confusing. She is both Black and Indian at the same time.”

As Ocran asserts, the argument that mixed-race people live in halves is, for the vast majority, simply untrue. I should know, with my own mixed-Punjabi Indian and white British heritage. I’ve often heard that mixed people have ‘chosen’ to align with one ‘side’ over another, even from mixed people themselves. The reality is that how mixed people are seen is rarely up to us, and leaning into one culture more than another can be a subconscious choice influenced by these external opinions. Neither do our experiences slot neatly into ‘sides’ – we are all of our identities and experiences at once.

Actor and author Jassa Ahluwalia’s recent release, Both Not Half, makes a powerful argument for blends rather than borders. “[Mixed people’s] existence makes emphatically clear that racial boundaries are a fiction, posing a threat to those who seek to wield power through tales of ‘us and them,’” he says.

“We must change the way we think about identity. None of us are half anything. We are all whole and multiple. ‘Is she Indian or Black?’ Kamala Harris is both.”

The understanding of multiracial identity is changing, but we’re far from a widespread understanding of the nuance of mixed identity. We need to open up this conversation before comments like Trump’s do serious damage to both mixed and monoracial communities.