After devastating earthquakes, it’s common to see discussion of earthquake prediction. An earthquake prediction requires, in advance, the specific time, location and magnitude of a future quake.

However, earthquake prediction has never been achieved successfully in a way which could be repeated.

Often, “predictions” are vague, such as describing the future earthquake as happening “sooner or later”, and the underlying methods are not scientifically founded.

That’s not to say we don’t know anything about what earthquakes will happen in the future. While earthquake scientists are not able to predict earthquakes, we are able to forecast them.

What’s the difference between a prediction and a forecast?

A forecast tells you the chance or the probability of a range of future earthquakes in a given region. This includes how big the quakes may be (their magnitude), and how frequently they will occur over a specified time period.

Earthquake forecasts are built on observations of past earthquake activity, which may stretch back decades, centuries or even thousands of years. These observations are analysed and modelled, and we use our understanding of the physics of earthquake occurrence to determine the chances of future seismic activity.

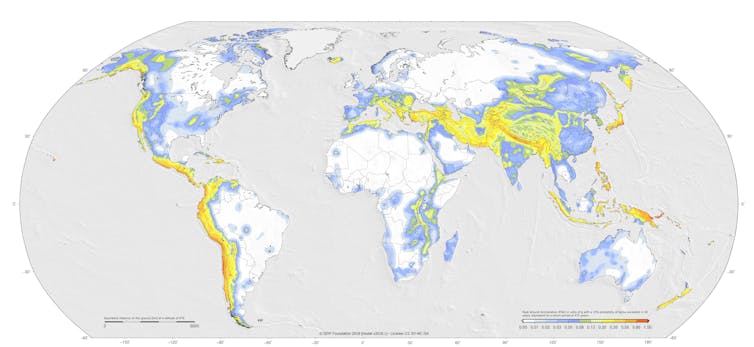

When looking at catalogues of the time, location and magnitude of past earthquakes, it becomes very clear that damaging earthquakes are more likely to strike along the boundaries of the tectonic plates that make up Earth’s crust than in the interior of those plates.

In recent decades, the installation of worldwide networks of seismic recorders has also allowed the detection of much smaller quakes and tremors – including events too small to be perceived by people. These data have revealed important relationships between the relative numbers of small and large earthquakes which underpin earthquake forecasting. Earthquake forecasts can be made for the short term (weeks, months, years) and the long term (decades to centuries).

How little quakes give us clues about big ones

One of the fundamental discoveries of seismology is the fact that, in a given region, there will be on average about ten times as many magnitude 2.0 earthquakes as magnitude 3.0 quakes. There will also be ten times as many magnitude 3.0 as magnitude 4.0, and so on.

This relation allows us to use small earthquakes, which happen often, to forecast less frequent, large earthquakes – which may not yet exist in historical records.

Observations and analysis of major earthquakes from around the world over the past century or more has also helped us to understand their aftershocks. These shocks diminish over time in a statistically characteristic way.

Read more: Satellite measurements of slow ground movements may provide a better tool for earthquake forecasting

This relationship is used for short-term forecasts of active earthquake sequences, to estimate the magnitude and frequency of earthquakes in the weeks, months and years following the main quake.

In these forecasts, large magnitude aftershocks are always possible, and in some cases, they can be larger than the mainshock. Such forecasts have been used in many countries around the world.

After the magnitude 7.1 earthquake at Ridgecrest, California, in 2019, a series of forecasts were released, and updated as new data was received. Currently, there is a 10% chance of one aftershock of magnitude 5.0 to magnitude 5.9 in the Ridgecrest region in the next year.

Knowing what to expect during an active sequence is important for planning how to respond and recover from a strong earthquake.

Records in rock

Geological investigations extend the record of major earthquakes beyond those captured in earthquake catalogues. These studies look for evidence of ground-rupturing earthquakes along a particular fault.

Take the Alpine Fault, a 600 km section of the boundary of the Pacific and Australian plates in Aotearoa New Zealand. Analysis of rocks along the fault has provided strong evidence that, over the past 8,000 years or so, one ground-rupturing earthquake of around magnitude 8.0 has occurred roughly every 300 years.

The most recent major rupture on the Alpine Fault was in 1717, more than 300 years ago.

Read more: NZ's next large Alpine Fault quake is likely coming sooner than we thought, study shows

Using this data, earthquake scientists have estimated that there is a high probability – a 75% chance – of rupture on this fault in the next 50 years. There is an approximately 80% chance that this earthquake will be a magnitude 8.0 or above.

This type of medium- to long-term forecast allows for preparedness such as planning for emergency response. In the case of the Alpine Fault, the AF8 program was put in place to keep the community informed and engaged, and to plan the response and build resilience for the expected future earthquake.

Maps and codes

Our best long-term forecasts use data from earthquake catalogues and geological studies, combined with earthquake behaviour patterns and other knowledge such as geodetic models – which use GPS networks to tell us how Earth’s surface is under strain and moving as tectonic plates shift.

These forecasts typically provide not just the magnitude and location, but also the range of the intensity of ground-shaking from future earthquakes.

Much like climate forecasts, these forecasts combine multiple models into a single forecast. This is used to map regions of low to high probability of experiencing damaging earthquakes.

These long-term forecasts inform building codes around the world, and guide the design and construction of buildings and infrastructure to withstand strong ground shaking from future earthquakes and, ultimately, to save lives.

Dee Ninis works for the Seismology Research Centre, and is Vice President of the Australian Earthquake Engineering Society.

Matt Gerstenberger is a member of the New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering and an Associate Editor for the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.