COVER STORY / SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2022 / SOCIETY

No Place to Live

One person’s search for a place to call home shows a public-housing system stretched to its limits

BY JULIA-SIMONE RUTGERS

ILLUSTRATION BY ROMAIN LASSER

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MIKAELA MACKENZIE

DATA VISUALIZATION BY ROBERTO ROCHA

Published 03:32pm, Sep. 21, 2022

On a spring morning in March 2021, Robert Russell thought he’d be a hero.

As smoke seeped through the thin drywall separating his apartment from a fire in the next suite, he ran into the hallway and kicked down his neighbour’s door. The room had been cleared out, save for a mattress leaning against the radiator on the wall. With a rush of fresh air from the hallway, the flames soared, lapped at the ceiling, and chewed through the insulation as they raced across the attic. With no one inside to rescue, Russell hurried out of the building to join the throngs of displaced residents in the lot.

News reports the next morning called the fire damage “significant.” Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service platoon chief Don Enns told media it took an hour and a half to bring the flames under control and added that the firefighters were “lucky” to contain the blaze to half of the twenty-unit structure.

Russell’s suite got the worst of it. Within an hour, his apartment—the first steady place he had lived in after years of homelessness—was swallowed by a foot of water and soot. Russell would spend the next eight months shuffling between rooms in the remains of the complex, which he accessed through social assistance, fighting an impending eviction, and—for the umpteenth time in a few short years—defending his right to a safe place to live.

It’s difficult to say exactly how many people are unhoused across the country, but the best guesses come from the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, an organization that researches the unhoused. In 2016, the COH’s most conservative estimate suggested at least 235,000 people experience homelessness in the country each year.

The causes of homelessness are as layered and varied as the people experiencing it. In Russell’s city, 71 percent of those experiencing homelessness in 2021 were men and 66 percent were Indigenous, according to the nonprofit End Homelessness Winnipeg. Experts theorize that men, in particular, find themselves unsheltered due to inadequate social and financial support, especially when navigating traumatic events, mental health challenges, job loss, or substance use. Indigenous people, who are vastly overrepresented in the homeless population, suffer the systemic pressures of colonialism—poverty, displacement from community, and racism—all of which limit opportunities for safe, affordable housing. Meanwhile, many homeless Winnipeggers have been in the child-welfare or prison systems and became homeless after transitioning out of those provincial services.

All of this is happening against the backdrop of staggering rents and stagnant incomes pricing more and more Canadians out of stable housing. A recent report from Rentals.ca indicated rents have been on the rise nationally since the latter half of 2021 and are only expected to keep climbing as the Canadian population outpaces the availability of housing. The average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Winnipeg climbed nearly 3 percent in 2021, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The CMHC also found that most urban centres lack affordable units for renters in the lowest income bracket, and the number of units available to them is steadily decreasing. The same data found “rent growth has exceeded wage growth in most centres” since 2020. In eight of the twenty-one urban centres studied, including Winnipeg, the average monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment exceeded 30 percent of monthly income at an average wage rate; in other words, the average rent in those centres is not considered affordable for a full-time worker making an average salary. The damage is hard to undo: at least some of these issues can be traced back to this country’s lack of investment in affordable housing for most of the past century.

Experts expect the rate of homelessness in Canada to rise too. Recent Statistics Canada data found about 3 percent of the population has experienced visible homelessness and another 15 percent has experienced “hidden” homelessness (like crashing on a friend’s or family member’s couch). While much of the national discourse around housing has focused on larger centres, like Toronto and Vancouver, oft-overlooked mid-sized cities, like Winnipeg, are increasingly facing their own housing-affordability challenges—and they’re responding in unique ways. Winnipeg, home to Canada’s largest urban Indigenous population, has started taking an Indigenous-led approach to housing solutions, hoping to curb its housing crisis before it spirals out of control.

Russell’s journey from tent cities to shelters, social housing, and private rentals shows that the city has a long way to go. His path through Winnipeg’s tangled network of housing supports and low-cost-rental options shows the pipeline to stable, affordable housing—purportedly the end goal of any social- or supportive-housing initiative—is itself riddled with gaps.

When I first met Russell, in the summer of 2020, he was one of dozens of people living in a bustling community of tents on a vacant swath of grass tucked near the rumbling Disraeli Freeway and Winnipeg’s cosmopolitan downtown core. He had once been a chef, cooking for high-profile diners like prime minister Justin Trudeau (eggs over easy, bacon, and toast). But, when his girlfriend died after a difficult struggle with ALS, Russell fell into a deep grief and chose to walk away from his condo and everything he knew.

At first, he tried living in a shelter, but life there can be unpleasant: residents can bring only so many possessions, and those are always at risk of being stolen; people who use drugs can’t do so in the shelter; and shelters can be violent. Many of them also require residents to leave in the morning and check in at night, a problem for those who work odd or late-night hours. It can also be difficult to transition out of a shelter into a steadier form of housing. While these spaces may offer a warm place to sleep and a hot meal, they often focus on day-to-day concerns and don’t always have the capacity to help residents take the next steps into long-term housing.

Like many unhoused people across the country, Russell and his partner, Meranda Mink, whom he’d met in the area, chose to leave the constraints of the shelters behind. Instead, they built a life at the tent community near the freeway. Russell was working odd jobs then: the occasional catering gig, piano moving, and whatever else he could find. He and others living in the encampment shared responsibilities and resources to help one another survive. But, in those early weeks of June, fire-prevention officers were wandering the long-standing tent community with orders for residents to vacate: everyone would have just a few days to pack their belongings, clean up their trash, and clear out.

Some residents were offered beds in the Main Street Project shelter; others searched for a new place to set up camp. A gaggle of protesters showed up to decry the evictions (though camp residents mostly paid them no mind), and a slew of reporters came to train cameras on the scenes of frustration, confusion, and desperation. At the centre of it all was Russell. The lanky, dark-skinned fifty-five-year-old bounced through the knot of tents, tarps, and overturned shopping carts, helping fellow residents clean up and connect with crisis workers. He fielded media requests, criticizing municipal and provincial policy makers who were leaving him and the other camp residents in the lurch. In the short time he’d been living there, Russell had become, in his words, “the mayor of the place.”

“This encampment is here because there’s no better place to be,” he told me at the time.

A few days later, all signs of the formerly vibrant community had been washed away. The city erected a tall metal fence—still there to this day—around the empty patch of yellowed grass. Though a couple of emergency shelters were just a moment’s walk from the camp, most residents simply moved their tents elsewhere in the city.

Eventually, Russell says, crisis workers stepped in to help him, Mink, and four others move into rooms on the ninth floor of a province-run social-housing building. This should have been the end of their housing woes, a way for them to transition into something more permanent; instead, it became a source of even more instability. Russell says the new tenants faced challenges adjusting to apartment living. They struggled to remember their building keys, and they faced noise and nuisance complaints from long-standing tenants of the Manitoba Housing building. Within a couple of months, Russell says, all of the new tenants had been written up and kicked out.

At its best, Manitoba Housing offers a reliable, low-cost housing option for families and is intended to form part of the community’s social safety net. Rent for suites is set at 30 percent of the tenant’s income (for those tenants with an independent source of funds) or is covered by their government employment insurance and assistance (EIA) payments. Eligibility for the units is based on need: in Winnipeg, tenants must make under $28,000 annually to be eligible for a studio apartment or $40,500 annually to be eligible for a one bedroom (it should be noted that the median income for a single individual in Winnipeg is $38,600 per year before taxes, according to the most recent census data). This is the bedrock of low-income housing support in Canada: each province is responsible for owning, operating, and managing social-housing units through a branch of its provincial government, and these units are propped up by federal and provincial investments.

In practice, though, the social-housing system is not as stable as it could be. Demand for low-income housing has only risen over the past several years, and Manitoba Housing (like many provincial housing providers) is facing a serious stock problem. It owned and operated just 11,800 units of housing in 2020/21. Another 22,400 units of low-income housing were provincially owned but managed through agreements with nonprofits. While that may seem like a lot, the wait list for placement in social housing seems untameable. At the beginning of 2021, there were 5,093 families on that list; a year later, the number had risen to more than 5,800. Russell and Mink felt lucky to be placed in Manitoba Housing suites during their most vulnerable days, but being pushed out for what Russell believes were minor infractions—behaviours that could have changed with time or wouldn’t have been an issue in a private home—was like losing a golden ticket.

The dearth of social housing in Canada is a long-standing issue rooted in federal housing policies aimed at encouraging home ownership that date back to before the Second World War.

The Dominion Housing Act was passed in 1935 and largely resulted in homes that were too expensive for the lowest-income families to access. The government tried again, in 1938, with the National Housing Act, which still focused on stimulating home ownership and created units that were inaccessible to low-income renters. Rates of homelessness and the number of “slums” were skyrocketing as the Great Depression continued, and overcrowding was becoming a major issue. Even after the war, when the government assumed increased supply and low-interest mortgages would help stimulate a homebuyers’ market, many Canadians still couldn’t afford to buy.

Between the 1940s and ’60s, the government amended the National Housing Act to include truly subsidized housing, whose funding and construction would be a shared responsibility between the feds, the provinces, cities, nonprofits, and co-ops. This worked for a time: units sprang up nationwide. More than half of Canada’s current social-housing stock was built between 1970 and 1989, according to CMHC data. But federal budget cuts in the ’80s and ’90s slowed down production, and the task of building these units was eventually passed down to the provinces.

The impact of those cuts still plagues the social-housing sector today. Provincial governments did little to fill the gaps left by the federal government. Annual investment in affordable housing declined by 46 percent between 1991 and 2016. Kirsten Bernas, who has been involved in the housing sector for more than a decade through her volunteer role chairing the provincial working group of the Right to Housing Coalition, says Manitoba’s social housing is “the most affordable housing that’s available to people on low incomes—and we’ve never had enough of it.”

The Winnipeg-based coalition, which brings together organizations and citizens concerned about the city’s shortage of social housing, has been advocating for investment in new social-housing builds at all three levels of government for almost fifteen years. Their request is simple: a provincial commitment to building 300 new units of social housing every year for the next five years. Those units—which Bernas acknowledges are a very conservative estimate of housing need—would cost the government only $60 million annually, less than 1 percent of the total annual budget. “We’ve been talking about it long enough,” Bernas says. “You just have to have the political will to put some of your budget toward housing.”

After being kicked out of Manitoba Housing, Russell and Mink faced perhaps their most challenging days. They had given away their tent and generator in the move and had to start over on the street. Another winter was approaching, and they needed a way out.

One November day, Russell bumped into an old friend who told him about an apartment complex near the airport that was accepting tenants on EIA. It felt like the other side of the world. But the complex on Elkhorn Street—composed of twenty suites in two ten-unit buildings—was spacious, clean, and safer than the tents. Russell met the property manager, Douglas Lughas, who explained the system at the Elkhorn complex: rent was $1,100 for a two-bedroom suite, but many tenants had their rents subsidized by EIA. By December 1, Russell and Mink had moved into a suite of their own. “That was when it was beautiful,” says Russell.

There were some early hiccups—a stranger kicked their front door in on the first night, shattering the lock—but it was nothing he couldn’t handle. He wedged furniture under the door handle for a couple weeks while pressing Lughas to replace the locks.

In time, the Elkhorn Street apartment became “the spot,” Russell says. “We’ve always been more mindful to the community that we live in to help out in any way possible. Harm-reduction supplies? We’re the people to come to. You need a place to shower? We’re the place to come to. You need a pair of socks? Sure. Gear? Come to us. Our place was like a shelter.”

The morning of the fire was supposed to be a special one: Russell and Mink were getting internet. Russell had gotten up early, made coffee for the Wi-Fi technician, and was distracted, trying to figure out what to name his brand-new network, when Mink’s cousin (who had been outside for a cigarette) popped his head in the door.

“He goes, ‘Hey, uh, I think there’s something going on,’” Russell recalls.

Russell says the building’s fire alarms hadn’t rung, but neighbours had noticed something was wrong and had begun filing out of their apartments, spilling into the parking lot below.

“I think your place is on fire,” Russell remembers the cousin saying.

By the time the smoke cleared, four of the ten units in Russell’s half of the building, 12 Elkhorn Street, were unlivable. Russell says Lughas offered him a two-bedroom suite in the unaffected building, 16 Elkhorn Street, but Russell offered the suite to a family of nine that had been displaced by the blaze. Instead, he and Mink crowded into a friend’s basement bedroom in the complex. Russell spent sleepless nights guarding the burned suite from would-be thieves as he worked to clear out the clothes and other belongings he and Mink had left behind.

There is little in the Residential Tenancies Act (the provincial manual that guides rights and responsibilities for tenants and landlords alike) that dictates how landlords should handle an emergency like a fire. To get discounts on rent or money for moving expenses, the tenants at Elkhorn would have to take it up with the landlord themselves.

But Russell remembers meeting a man he believes to be the building’s owner in only brief encounters after the fire. The first licks of spring had filled the potholed Winnipeg streets with slush, so it caught Russell by surprise when, just a day after the blaze, a low-slung, Fudgsicle-brown sports car crept into the Elkhorn parking lot. “Oh man, that chocolate brown was so nice,” Russell crows. “He stepped out of that thing . . . . I was like, ‘Damn, this guy is good.’ I admired it. I was just in awe. I’ve never seen money like that, not in Winnipeg.”

The awe didn’t linger long. Russell says the man (who never gave his name) asked him what had happened, and Russell laid out the facts. “He didn’t ask me where I’m going to stay tonight, do I need any help,” says Russell. “He just shrugged his shoulders, said, ‘Things happen’ . . . and drove off.”

In the weeks, then months, that followed, tenants were left out to dry. Russell and Mink had been shuffled again, this time to a second-floor suite on the far side of 12 Elkhorn. The electricity had been cut off, owing to the fire damage; the building was left without water for weeks; several suites were missing locks; and some were missing doors. (Lughas denies all this. In an interview, he insisted that everyone living at 12 Elkhorn moved out immediately after the fire.) Russell remembers filling buckets of water from 16 Elkhorn’s outdoor faucet and hauling them upstairs to flush toilets and wash dishes. He barricaded the doors of his suite at night. He ran extension cords out his window and across the pathway to a basement suite in 16 Elkhorn for power. But Russell says he was still charged rent.

In June, months after the fire, tenants were told that the damaged building would be renovated and that they were to move out by July 1. But, with just a few weeks’ notice, the last tenants had nowhere to go. (Landlords in Manitoba are required to provide at least three months’ notice for evictions related to renovations and are expected to provide up to $500 in moving costs.)

Russell dug in his heels. He knew he couldn’t stay at Elkhorn forever, but he refused to leave without compensation for the moving expenses and the months of rent he had paid to live in overcrowded or damaged suites. He vowed to get something, anything, for the owner’s carelessness and even felt he would go to court if he had to. There was just one problem: to challenge the owner in court, he had to find out who the owner was.

With shelters full, dangerous, or undignified, and social-housing options all but impossible to land, many low-income residents turn to the private market—a largely unregulated nest of uncertain building conditions, fluctuating rents, and impervious landlords.

The people who own and distribute those properties are bound to hardly any standards of livability or affordability. There are, of course, laws to follow, but Winnipeg’s enforcement processes are complaint driven and mired in red tape, leaving many renters on their own against a tide of bad landlords, pesky pests, inflated rents, and crumbling infrastructure.

A 2022 rental-market assessment from CMHC showed vacancy rates of affordable suites in Winnipeg trend significantly lower than more expensive suites. People in the lowest-income quintile, those with annual earnings of less than $25,000, should be spending no more than $625 per month on rent, the report notes. These individuals and families—who make up 20 percent of the city’s renters—can afford to live in less than 3 percent of the city’s rental suites.

The scramble for affordable rent can give way to desperation. As Russell puts it, “When you’re trying to get off the road, get off of being homeless, you’re looking for anything. It’s perfect for these slumlords. They’re just waiting for someone who’s just, like, begging for something.”

In cases like Russell’s, holding a landlord to account can involve tedious searches through records just to find a name associated with the property. A search through city hall records revealed that the Elkhorn complex was registered as a condominium and that each suite was therefore owned separately. The twenty suites at 12 and 16 Elkhorn were registered to five numbered companies and two individuals, each linked to a handful of residential and business addresses across the city. Outside of city hall documents, there’s little record of either individual named in association with the complex. Social media searches yielded few answers, and reverse 411 searches turned up empty. Aside from the fact the individuals are listed in the city’s tax records, there’s little other information about who they are.

Among the numbered companies, a thornier picture emerges. Four of the five companies have been dissolved since the mid-2010s. And, while the names of the directors for each of the companies are different, most list the same mailing address: 186 Henderson Highway, which houses a legal office.

Only one name is associated with the remaining active business: Sukhjit Bhandal, a real estate lawyer at the same office, that of Bhandal Law. He lists the same residential address as many of the other directors and owns 10 percent of the company’s shares. His name reappears in another of the numbered company files, this time as the 100 percent shareholder.

In and of itself, the murky picture of the building’s ownership is not particularly nefarious—individuals purchase properties under numbered companies, either to separate their assets or get a break on taxes. As long as the city’s taxation department gets its annual property tax cheque, it’s unlikely the department would ever notice a property is registered to a defunct business.

It’s not uncommon for a landlord to be responsible for multiple units in a complex but split them across several businesses (each with different directors) to keep taxes low and spread liability. “We see this all the time, and it’s definitely part of the frustration,” says Chantal Smith, program lead for a North End housing-support program called Tenant Landlord Cooperation. “[If] it’s owned by numbered companies, it feels like sort of a shell game when you try to hold people accountable that don’t want to be held accountable.”

Ownership structures like this can have serious implications for a renter. It cost over $70 to access enough condo plans and company records to tie Bhandal to the property—too steep a cost with too many complex processes for many a time- and money-strapped renter. (Bhandal himself never responded to multiple requests for comment from The Walrus.) In the case of emergency, mistreatment, or any situation where a renter may want to get in touch with their landlord, no one is to be found.

Russell and the other tenants stayed at the remains of the Elkhorn complex until October—seven months after the fire. In the end, it was city crisis workers and fire prevention, ironically, who forced the eviction, claiming the property was a safety risk. In the final weeks, some tenants got help from Smith and the team at Tenant Landlord Cooperation, which educates tenants and landlords about their rights and connects them to income supports, mental health agencies, and other resources.

Smith and her team negotiated with Lughas and with fire prevention on behalf of tenants, explaining many residents had nowhere else to go, and eventually secured a potable-water supply and a few extra days for tenants to find new housing.

For his part, Russell, who had started a job as a peer-support worker at a nonprofit, found a connection who pointed him to an apartment back in downtown Winnipeg, where he and Mink lived for a few months. Still, feeling exploited and being evicted from the Elkhorn complex, his first real home in many years, left him with a sour taste in the mouth that just won’t fade.

Experts believe there’s a better way—that supportive-housing initiatives can and should form part of the pipeline toward safe, permanent, and affordable housing and can offer enough stability to allow people to rebuild other aspects of their lives. One of Winnipeg’s most successful housing projects, the Bell Hotel, was built on this very premise.

In the early twentieth century, the building was considered among the finest accommodations in the city. Winnipeg was in its brightest days. Considered a hub for transportation and commerce, the city bet its prosperity on trains. Stations for the cross-country rail lines, shuttling passengers and goods from the eastern shores, popped up through the centre of town. To manage the influx of people, the Canadian Pacific Railway built a sprawling station complex just off the northern segment of Main Street—close to North Point Douglas—and the neighbourhood soon attracted a network of beverage rooms, restaurants, billiard halls, and small hotels, including the Bell.

Unfortunately, history was not kind to the hotel. The hospitality industry was gutted by the world wars, and construction of the Panama Canal, in the mid-1910s, diminished the importance of trains. By the end of the First World War, downtown Winnipeg’s most prosperous days were gone. Shelters, food banks, and visible homelessness were on the rise; people on fixed incomes began taking up long-term residence in the downtown hotels. According to Heritage Winnipeg, by the 1980s, the Bell’s seventy-five single-room units had become “last resort housing.” By 2007, the hotel was closed.

But an experimental partnership was brewing. CentreVenture, an arms-length city agency with a mandate to help develop the downtown, teamed up with several provincial ministries, the Winnipeg Housing Rehabilitation Corporation, the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, and Main Street Project, to purchase the dilapidated hotel and develop a new supportive-housing model there. In 2011, the Bell reopened with forty-two units of permanent, supportive housing for single adults who were struggling with chronic homelessness and complex health and social needs. The Bell, in collaboration with community partners, hosts on-site supports for health, education, income, employment, and substance use. Each of the upper floors is home to a small collection of laundry machines and rows of single-occupancy suites, complete with bathrooms, kitchenettes, and beds.

Kerri Smith, manager of housing services with Main Street Project, explains that what makes the Bell model special is that it falls somewhere between supportive housing—where programming and supports are often mandatory conditions of tenancy—and independent living. Tenants can opt in to whatever supports they need (or ask for additional supports) and opt out of what doesn’t serve them. Some tenants in the four-storey hotel get help with medication or with substance use. Some ask on-site staff for regular check-ins as they go about their days. Others live almost entirely independently, using only the shared mailroom.

Tenants—whose rents are set based on income—are welcome to stay as long as they’d like. The average length of stay is approximately four years, says Smith. Some tenants eventually transition to other housing, but others live at the Bell until the end of their lives.

A Winnipeg Regional Health Authority study, conducted over the first thirteen months of the Bell project, found the original thirty-five residents’ contact hours with police dropped by more than 80 percent after moving into the Bell; hospital visits similarly dropped by more than 50 percent. “It’s way cheaper to keep somebody here, housed and relatively healthy, than it is for someone to be taking up space in an emergency shelter,” says Smith.

The success of the model, Smith says, comes down to the program’s partnerships and flexibility. Where some transitional-housing programs work to push residents into independent living, the Bell is open ended, leaving the decision-making power in the hands of the tenants themselves. “We can’t just push people out of the nest and then expect them to be okay and drop all those resources,” Smith says of transitional-housing models. “Those resources that people are attached to have to go with them.”

More than just a room to live in, the Bell, Smith says, is a community—at times, a family—that works together to keep its members safe, healthy, and housed. “There’s that term, ‘it takes a village to raise a child,’ and that’s exactly how this works,” says Smith. “We need the village to come together to help marginalized individuals who do not have homes.”

The Bell has been heralded as a possible solution to the housing crisis. Main Street Project executive director Jamil Mahmood says more Bell-style buildings, each with its own focused services and resources, could help curb homelessness. The Bell is limited to single individuals without pets, but a similar model with larger suites, or a model focused solely on mental health and addictions, or one designated just for women could chip away at the complex vulnerabilities that leave people without a place to call home. Ultimately, experts say, nonprofit-housing models operate with an on-the-ground perspective and are able to meet specific needs on a community-by-community basis, which can make them an ideal way to house vulnerable people.

Over the past several years, the provincial government has been off-loading some of its social-housing units to nongovernmental organizations, but those groups have struggled to maintain enough funding to offer the same benefits. As Christina Maes Nino, executive director of the Manitoba Non-Profit Housing Association, explains, nonprofit housing built after 1985 benefited from funding agreements with the provincial governments that subsidized operating costs—think repairs, maintenance, and utilities, for example—for a full slate of units rented at rent-geared-to-income rates. But these agreements are expiring, and even with the launch of new federal programs, nonprofits aren’t always sure where the money will come from next. “Every year, people sort of hold their breath and hope that it happens,” says Maes Nino.

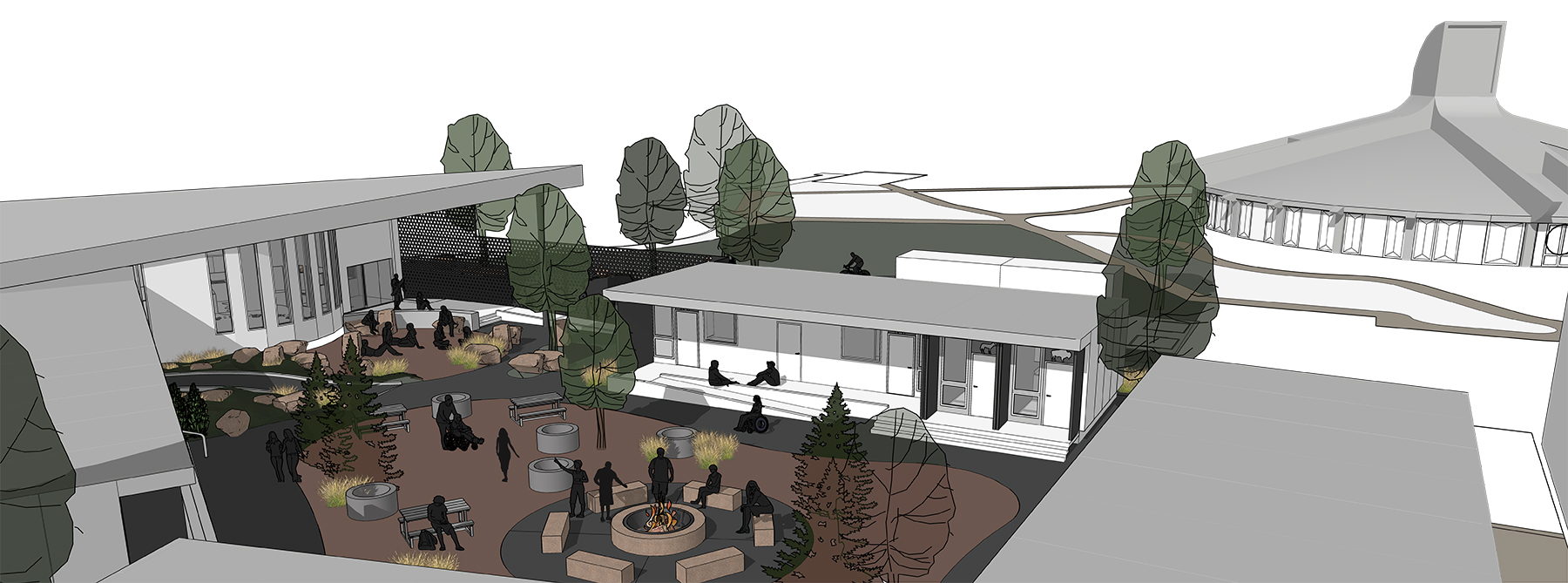

A newer project in North Point Douglas is focusing on community. Astum Api Niikinaahk (meaning “come sit at our home”) is a supportive tiny-home project that will include housing and healing resources right where they’re needed most.

The twenty-two units will be small. They’ll each include a washroom, a storage cabinet, a sink, a two-burner stovetop, a mini fridge and freezer, a microwave, a daybed, and a two-person dining table. It’s the bare essentials, but it’s not all the community will have to offer. The suites will be arranged in a circle, and the complex will include a lodge and an outdoor gathering space. Melissa Stone, Astum Api Niikinaahk coordinator at the Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre, says that, in the lodge, residents will be able to access guidance from Elders, a medical clinic, laundry facilities, and a commercial kitchen (which they plan to use for food-handler courses, cooking and life-skills workshops, and, of course, community meals). The lodge will also host offices for 24/7 staffing—including for harm reduction and housing support—and a seating area for programming, meals, and activities. Outside, the landscapers will design firepits, seating, and a garden for growing traditional medicines. There will be room for ceremony, gathering, and connecting with the land. Residents will pay for their space through their income or through social assistance, in much the same way that affordable housing works.

Above all, Stone says, the project has been guided by direct consultation with the people it hopes to serve. After the encampments, where Russell and Mink lived, were dismantled, Ma Mawi and six other Indigenous-led agencies held a ceremony in the community and spent weeks walking the North Point Douglas neighbourhood to arrange a public meeting where they would start defining the project. At the meeting, the agencies handed out food and harm-reduction supplies, including clean needles, and asked what residents would want in a housing project.

Overwhelmingly, unsheltered residents in the neighbourhood said they didn’t want to live alone. The shelters in the area felt unsafe, but the most-affordable low-income housing was outside the neighbourhood and far away from the communities that had been built among the shelters and tents. “Lots of individuals living on the street and unsheltered have street family,” says Stone. “That need, to have safe, supported communal housing, was what they were asking for.”

Scheduled to open in fall 2022, Niikinaahk is one of several housing projects launching in Manitoba. On November 23, 2021, newly minted premier Heather Stefanson promised a homelessness strategy that would emphasize a whole-of-government approach for consultations with Manitobans.

The outcome of those discussions was clear: residents wanted the province to prioritize housing that offered dignity, cultural safety, and access to services that meet a wide variety of needs. Community members stressed the need for a “major expansion” of social-housing options, including housing with built-in social supports, and noted most affordable housing wasn’t actually affordable to low-income families, indicating more rent-geared-to-income units should come on the market in the private sector. Notably, respondents pushed for long-term and sustainable funding for nonprofits in the housing sector. The government’s goals are lofty, but the province’s hands remain tied by historical cuts to federal social-housing funds.

Industry stakeholders have taken some comfort from the National Housing Strategy—the Trudeau government’s $70 billion attempt to mitigate and confront the worsening housing crisis across the country—which represents the largest investment in social housing the country has seen in decades and the country’s first attempt at a holistic housing plan. The strategy is set to run for ten years and includes funding to repair dilapidated housing units and build new affordable-housing stock through partnerships with provincial governments.

Still, it can be hard to be hopeful. Critics worry the federal and provincial programs will do little to bolster the net number of available units. Part of the problem seems to be that Canada’s political class isn’t affected by affordable-housing policies. Many are themselves landlords or rental-property owners. In February 2022, for example, a Winnipeg Free Press investigation found that Premier Stefanson failed to disclose more than $30 million in real estate sales—including two apartment complexes that she partly owned through shares in a holding company. When the apartments sold in 2019, Stefanson was serving as the minister for housing.

A t Elkhorn, nearly a year after the fire, the burned half of the building remains stripped down to its wood frame. I met Russell and Mink at the site in February 2022, standing in the bright sun and bitter cold as crews worked diligently to remodel, perplexingly, the undamaged wing of the complex. They pointed to a corner suite on the edge of the burned building: it had been theirs.

Looking up at the shell of their former home, Mink reflected on the year since the fire. “I had just finally got comfortable, got it to what I wanted it to be. I was actually just starting to plan on getting visits with my nephews and then that happened, and it seems like ever since then, it’s been so hard to get to where I was when I was here,” she said. “It’s just not the same.”

The pair have struggled to get rent payments from an overburdened and unresponsive EIA system; they’ve had to jump through hoops to make appointments with case managers and to ensure their payments are enough to meet their basic needs. “We’ve managed to stick it out and not be homeless,” Mink said. “But how long do we have to go through this?” It’s demoralizing and dehumanizing, Mink said, to be surveilled by and dependent on indifferent government institutions. When the fire took everything from them, neither the Red Cross nor EIA nor the city nor the landlord, whoever that may be, offered any concrete support.

“It makes you feel kind of worthless,” she said.

“No one within the system is looking out for your best interest,” Russell added.

The two have since parted ways. Russell is waiting for placement in a Manitoba Housing complex in North End, a neighbourhood where he’s always felt at home; he hopes this time he’ll be able to stay for good.

This story was reported and written with the support of the Justice Fund.

The article is a co-publication of The Walrus and the Investigative Journalism Foundation.