I was at a kids’ soccer game and there were children everywhere. The environment was high-stress and even as an adult it was easy to feel overwhelmed just from being there. (Children in groups inexplicably scream.)

Among the chaos was a little girl about three years old, crying and flailing on the floor of the grandstand, while her mum paced around her, urging her to get up, leave the grounds and walk to the car so they could drive away.

It went on for several minutes and the mother was starting to shout and threaten, demanding the kid comply: “Let’s go. Come on. We need to go to the car. Hurry up. Get off the ground.” People were watching.

The kid wouldn’t have a bar of it and was screaming to the point where I was wishing I’d brought earplugs.

I was ALMOST tempted to weigh in. But just because you can doesn’t mean you should be out in the world giving advice about parenting. Advice is like debt: no one wants it and if we get some, we’ll do our best to ignore it.

Parenting advice is particularly fraught. Vulnerable mums who are tired, struggling and already dealing with enough extrinsic pressure to be “perfect” do not need to hear our thoughts and opinions. Having been one of those mothers myself, I can say that getting unsolicited advice on what you’re doing wrong as a parent is the last thing you want.

That said, what may seem obvious to one of us may have utterly eluded another.

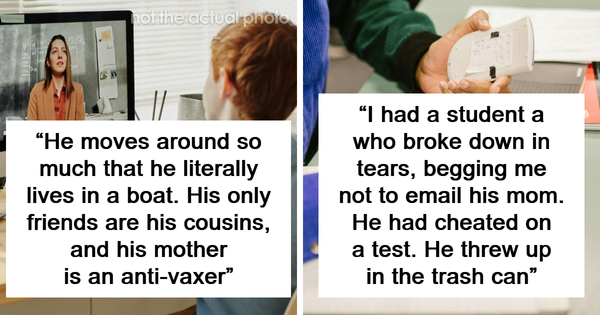

It took me to some advice I heard when I used to interview experts on TV. This particular expert was a child psychologist who came on to talk about how to deal with meltdowns. And their advice was so basic and applicable and such common sense that I took it – because I needed to be told – and have been applying it ever since.

When anyone – child or other – is having an intense emotion, whether it be rage, despair, terror, happiness, exhilaration, anything, they’re not going to be taking in information. If the child is upset, their first need is to be seen and acknowledged.

So for instance, if they hurt themselves, they don’t want to hear you say, “It didn’t even bleed! You’re fine. Up you get.” They need you to say something like, “Ouch! That must have hurt! Oh, you’re so upset. It really got you, didn’t it?”

If they fall, they don’t want to hear, “You shouldn’t have been climbing that tree!” They need to hear something like, “Wow, I saw you fall! Are you OK? That would’ve knocked the wind out of me. Did it knock the wind out of you?”

If they’re angry, they don’t want to hear, “Stop it and get in the car!” They need their experience to be validated. So you say, “Oh, honey, I see that you’re angry right now. It’s a big emotion. What happened?”

The kid doesn’t need you to leap into problem-solving, and definitely not that particularly scary breed of parental vigilantism that is expressed through declarations such as: “Show me who did this to you!” “Wait til I get my hands on them” or “I’m going directly to the principal!”

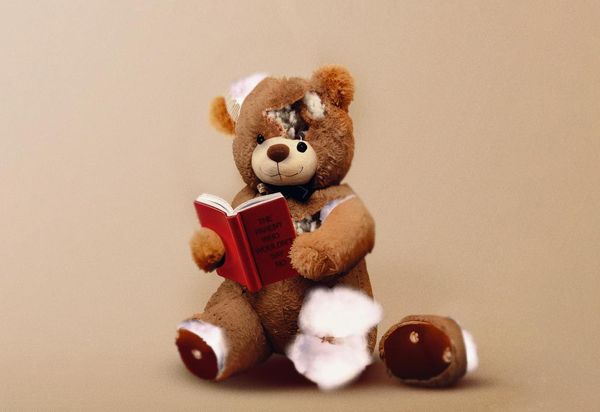

It helps me to think of myself as my child’s support animal. The support animal is stoic and silent. They can’t berate or problem solve. (I always picture a beautiful, dignified chocolate labrador called Houndypoo.)

Houndypoo just shows up in stillness and sits with the child in a state of calm. He sits with them through their big feelings. He doesn’t try to hurry the child along to “finish” having the feeling. He’s just present, witnessing. This is so helpful to the child. They can exhaust their tantrum and stroke their support animal. They can be petted and kissed and heard. And then when it’s over, when they’re ready, they can talk it through.

The thing I like about the support animal is that picturing him helps me calm down. I find my centre and then I am regulated, ready to show up in support of my person.

And if you’re the child’s parent, you ARE their best, most favourite and trusted support animal. There is no one better qualified for showing up as the labrador than you.

I asked one of my adult children what she thinks makes good parenting when a child is upset. She’s now 20 and still actively remembers being a kid.

“I remember when I had my first heartbreak and I told you about it while you were rubbing my back in bed. My heart was hurting so much!

“There was a boy who I’d gone ghost hunting with twice at recess and I told him at the start of school that I liked him, and he told me by lunch that I was dumped. And I just cried! In the bathroom. Our relationship lasted two whole hours.

“Looking back it’s funny and it’s fine but at the time I felt like I had genuinely experienced a tragedy. I didn’t even tell Mira (my best friend) because I was so embarrassed.

But I did tell you that night and you just listened while you scratched my back. And you said, ‘That sounds so hard, Dee Dee!’ And I said, ‘Yeah!’ and you repeated the feeling back to me. And we felt it together while you rubbed my back.”

• Yumi Stynes is an Australian TV and radio presenter, podcaster and writer