Strange to think now, but when Tool released 10,000 Days in 2006, many fans felt they’d taken too long to return, and that they’d lost momentum as a result. But as Maynard James Keenan and co have proved time and time again, it’s best not to write them off. In 2010 Prog took a look at the story so far of an art collective who refuse to be easily defined.

Some music isn’t meant to be understood: it’s just too difficult. Strip it down, analyse it, work out how to play it and you still won’t get it. Look at Tool, the Los Angeles prog-metal quartet, for example: the music they play is impossible to quantify, with riffs switching between brain-addling time signatures and a barrage of atmospheric effects masking and transforming everything.

Then there’s the lyrics, about which an entire online community orbits, attempting to decipher their meanings: do they mean what we think they mean, or what we’re supposed to think they mean? There’s enough complexity in the music, lyrics and images on Tool’s four albums to date to fill several lifetimes’ worth of study. Good luck with that.

Tool trod their own path from the very beginning. You may recall the rise of the US alt-metal movement in 1990 or thereabouts: the grunge scene was on the brink of a commercial explosion, and the funk-metal movement was in full swing. Somewhere between Nirvana and Faith No More were Tool and Rage Against The Machine, LA bands whose members had known each other as far back as high school.

Adam Jones and RATM’s Tom Morello had been in a school band called Electric Sheep before embarking on different careers: after attending art school, Jones ended up in Rick Lazzarini’s Character Shop in Hollywood, where he worked on cheesy rent-a-sequels such as Predator 2, Ghostbusters 2 and even A Nightmare On Elm Street 5: The Dream Child. Honing a gift for claymation animation, Jones was as much a visual artist as a musician.

The next key to the Tool conundrum came from Danny Carey. Like his contemporary Mike Portnoy of Dream Theater, Carey was far more than just a skins-basher, bringing an awareness of philosophical theory and occult symbology to the band along with his brain-achingly complex poly-rhythms.

“I’ve always been fascinated with sacred geometry,” said Carey, explaining why he draws arcane shapes on his drum heads. “It’s about tracing the manifestation of matter into the physical world. The lunar current, rather than solar current, is what Tool is about.” Not your average drummer, eh? Add a bassist, Paul D’Amour (replaced by British four-stringer Justin Chancellor in ’95) and all that was needed was a singer…

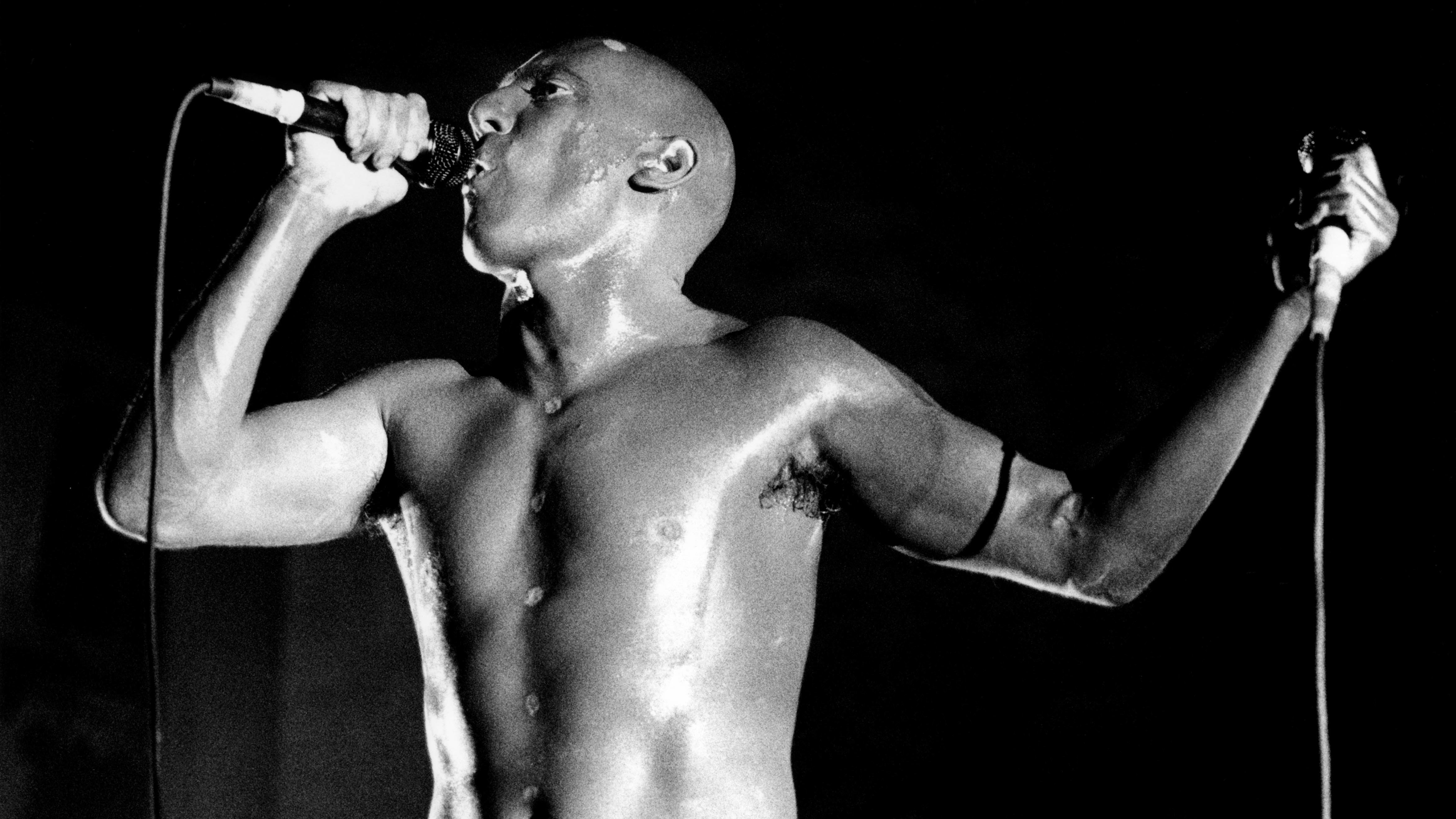

Maynard James Keenan is, as the many ‘MJK Is God’ internet newsgroups attest, no ordinary human being, and indeed no ordinary rock star. A small, bald geezer who hates doing press because so many journalists are “buffoons who couldn’t manage a Starbucks” (his words), he finds the glitter of the Californian showbiz industry repellent.

I like a picture that makes you uncomfortable on one hand and it’s beautiful on the other. It’s gross, but you look anyway

Adam Jones

Furthermore, Keenan has advanced views on more or less everything and is full of contradictions: he’s a soft-voiced singer in a crushingly heavy band; a left-wing campaigner who did time in the military at the über-establishment West Point Academy; and a vineyard owner who barely drinks.

Keenan picks his friends carefully, enjoying a close friendship with Tori Amos but incurring the wrath of Courtney Love, although you’d expect the exact opposite from an alternative-metal icon. After a spat with Love, he famously created the ‘Free Frances Bean’ T-shirt range in the mid-90s.

He explained: “Everybody was trying to get us to do benefit shows, like ‘Free Tibet’. And I was gonna have my own platform: ‘Free Frances Bean’. Just watching the tornado that is her mother, my first thought was, ‘Oh my God, how is Frances Bean [Cobain] gonna survive this insanity?’” Love retorted by labelling Keenan a “media whore”, which he thought hilarious under the circumstances.

After recording a taster EP called Opiate in 1992, Tool released their debut album, Undertow, the following year. Many of Jones’ early riffs echoed those of Morello, who had released his own first album with Rage the previous year, but in every other way the two bands differed.

Where RATM were overtly political, Tool addressed darker, more obscure subjects, specifically on the single Prison Sex, which concerned child abuse. Its video, a claymation affair directed by Jones, was terrifying – without resorting to violent images or the subject matter which many people assumed must be the song’s theme.

The clip was duly banned, although it often surfaces in academic discussion in the psychiatric field. Another single, Sober, came with an equally unsettling video in which a claymation prisoner in a shadowy dungeon breaks open a heating pipe to discover greasy, faecal chunks of meat flowing through it. As Jones said: “I like a picture that makes you uncomfortable on one hand and it’s beautiful on the other. It’s gross, but you look anyway…”

All this heavy stuff caused many metal fans to make assumptions about the members of Tool. They were said to be freaks, or malcontents, or psychopaths, when in fact the four men have spent most of their careers protesting that they’re just average Joes with more than average talent.

Understandably, most people ignored these claims when 1996’s Ænima was released – a truly sophisticated album that upgraded the raw vitriol of Undertow to a sleek malevolence that is still rather stunning today.

Dedicated to the band’s late friend Bill Hicks (who appeared in the artwork as ‘Another Dead Hero’), the album combined epic, Pink Floyd-style soundscapes with Keenan’s scathing lyrics – and in doing so, elevated Tool to an entirely new plane: the hitherto niche territory of prog-metal.

A single, Stinkfist, kept controversy levels high, with Keenan sniggering at the predictable reaction to the song’s eye-watering title: MTV refused to air the video under its real name, renaming it Track #1, although the sexual implication was merely a metaphor.

By now Tool were having fun with their many critics, staying three steps ahead of those who tried to understand them and issuing red herrings as they went along. No-one really understands why Carey likes to have Enochian magic symbols in Tool’s rehearsal room, why Keenan chooses blue body paint and female lingerie as stage-wear, or why Jones creates such disturbing, biomechanoid art: they just pretend to.

The point, Keenan reiterates, is for the listener to find an individual interpretation of the maze of information – and the fans have done just that online, discussing every nuance of Tool’s work, provoked in part by Keenan’s initial refusal to publish his lyrics.

Religion is basically a marketing plan. They’re going to trick you into giving up your civil rights over some storybook

Maynard James Keenan

2001’s Lateralus was Tool’s Dark Side Of The Moon, the culmination of everything which they’d worked to achieve. A monumental achievement, the album led to delayed recognition by the American record industry, which awarded a Grammy to the lead-off single, Schism.

Perhaps the rise of lowest-common-denominator rap-metal bands such as Limp Bizkit – whose singer Fred Durst’s oft-stated love of Tool was not returned, tellingly – had led the metal-buying legions to look for something more challenging; maybe Lateralus’ hypnotic redefinition of heavy music was impossible to resist. Either way, Tool now had a huge audience, and were able to perform stadium-level tours every few years, rather than the constant club-level grind of the Undertow era.

After 9/11 and George W Bush’s War On Terror, there was a perceptible shift in Keenan’s lyrics. Enraged by US foreign and domestic policy, the American church and the control of the public by right-wing news outlets like Fox News, he formed a new band called A Perfect Circle, which ran in tandem with Tool until 2004.

“Religion is basically a marketing plan,” he once spat. “They’re going to pass a plate in front of you, trick you into giving 10 per cent of your income to some child-molesting fuckhead, or worse, trick you into giving up your civil rights over some storybook.”

Poised on the brink of global superstardom, Tool took their time over their next move. Keenan had his new band to play with, as well as a vineyard in Arizona. Jones forged a second career as a sculptor.

Carey and Chancellor wrote new material, waiting for Keenan to return. For some fans, the hiatus went on too long: when the fourth Tool album, 10,000 Days, appeared in 2006, it was felt that some momentum might have been lost.

Still, the record was truly sumptuous, with the CD sleeve containing embedded glass lenses in order to view the stereoscopic artwork inside. Three singles (Vicarious, The Pot and Jambi) were as gripping as ever, and their videos as eyeball-searing as before – but it was thought by several critics that some focus was missing.

Despite this, 10,000 Days is a dozen times deeper and more intense than any album released in recent years, with the honourable exception of contemporary prog-metal bands such as Mastodon and Isis. What do the critics know?

As for the future, Tool are playing a handful of dates this year, and there are rumours of a new album. It’s redundant to ask where they’ll go from here: they elevated themselves from the status of a mere band a long time ago. Tool are a bona fide cultural phenomenon – and one that only the prog-metal movement could provide. Like I said, some music isn’t meant to be understood…