Giovana Serrao was not home when a fire lit in a neighboring agricultural field got out of control and destroyed her acai palms on the island of Marajo in the Brazilian Amazon.

Paulinho dos Santos remembers the dark nights in November when he would leap out of bed to use buckets of water to douse flames threatening his farm.

And Maria Leao's two daughters suffered sinusitis, caused by a smoke cloud that for weeks enveloped Breves, the largest city on the island, surrounded by sea and rivers in the northern state of Para.

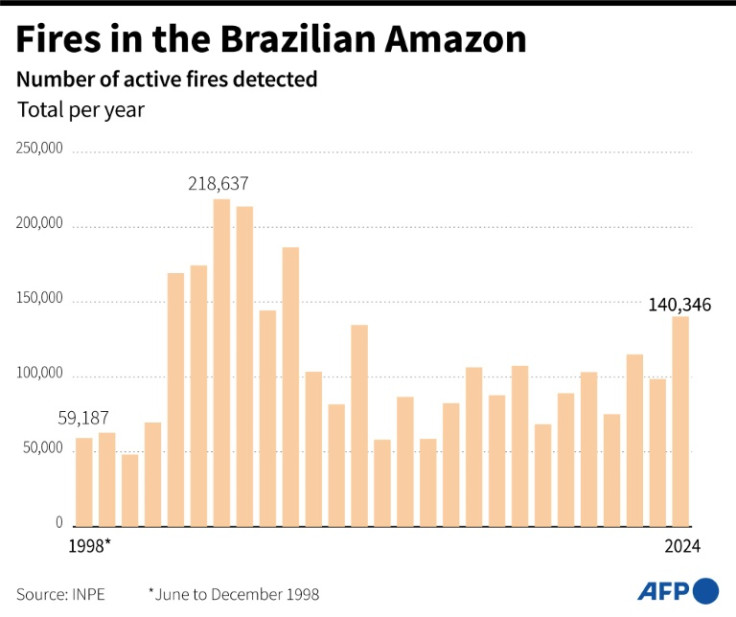

Like them, many residents of the region felt the brunt of blazes in the Brazilian Amazon, which had over 140,000 fires in 2024 -- the highest number in 17 years.

The situation was worst in Para state, whose capital Belem will in November host the COP30 climate conference, with more than 56,000 fires during the peak of the fire crisis last year.

According to scientists, the fires were linked to global warming, which dries out vegetation and makes it more flammable.

But they are almost always started by people clearing land for pasture or agriculture, or for illegal logging.

"We lived through intolerable weeks. We couldn't even go outside because visibility was zero. The medical center was overwhelmed with patients suffering from respiratory problems," says Zairo Gomes, a 51-year-old teacher and a prominent civil society figure in Breves.

At the time, the air quality monitor at the city's federal university recorded 480 micrograms per cubic metre of harmful fine particulate matter (PM2.5), far exceeding the WHO's 24-hour limit of 15.

Breves, an impoverished city of 107,000, relies primarily on its river port connecting Marajo with Belem, the state capital.

Unemployment is widespread, and much of the population depends on farming acai fruit, a staple in Para's diet.

Authorities were notably absent during the two-month fire crisis from October to November, Gomes notes.

The city's open dumps, swarmed by vultures amid a strong stench, reflect the lack of sanitation.

When contacted, neither the mayor nor the environmental secretary responded to AFP requests for information.

The wave of fires sparked an unprecedented grassroots mobilization.

"We achieved something crucial: citizens began talking about the environment, climate change, and criminal arson. We stopped passively suffering," says Gomes.

This led to the creation of a collective called "Breves Asks for Help: The Right to Breathe," which regularly meets to pressure authorities and prevent similar destruction during the dry season, which starts every July.

"We want more resources for local firefighters, who are overwhelmed, and punishment for those responsible," said Maria Leao, a 50-year-old midwife and activist.

Greenpeace data highlights that most Amazon fires go unpunished, and less than one percent of fines levied are paid.

"We lack resources to fight the fires and apprehend those responsible," admitted Lieutenant Colonel Luciano Morais, at the Breves military police headquarters.

This year, "we made only two arrests" because proving responsibility is "very difficult," as fires are often started at night, he said.

At those hours, the forces "avoid entering the forest. And no one wants to talk," whether out of fear or ignorance, he conceded.

Outside his farm on the city's outskirts, Paulinho dos Santos, 65, said he doesn't know who started the fires that kept him awake for nights.

"Maybe it's better that way because I could have done something reckless," he said, still shaken.

The retiree lost vegetation across 40 percent of his land, though his house and chicken coop survived.

Serrao, however, pointed to her neighbor, who destroyed her acai plantation while burning his field for farming.

"The police spoke to him, but he is still there," said the 45-year-old woman.

Serrao and her husband planted her palms seven years ago with a bank loan they were finally about to repay by selling acai to Breves's schools.

"Now we don't know what we'll do," she said, standing among the charred trees.

Beside her, Gomes added: "We need to organize and unite with neighboring towns also seeking help. We're in the same struggle. No more fires!"