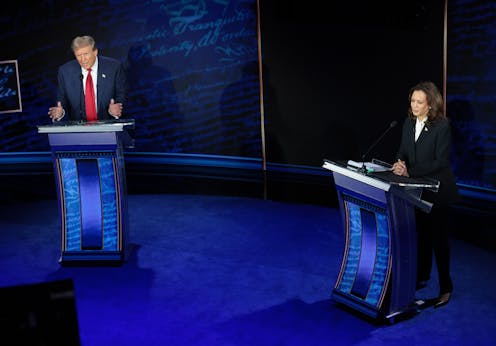

When Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump said during the presidential debate on Sept. 10, 2024, that Haitian immigrants are eating pets, food historians like me were not surprised at the slur. Trump’s lie followed a long American history of peddling ugly rumors about immigrants stealing and eating pets.

Dietary rules that unite and define American cuisine can so easily be perverted to use disgust to divide Americans. In the U.S., cow is food and dog is friend. Chicken is food. Cat is companion. The sharp lines between the animals Americans eat, love, protect and exterminate help write the dietary rules that define American norms.

What we eat, what we don’t and with whom we break bread are just some of the food rules that unite and define Americans. Think of how turkey – or tofurkey – unites Americans behind the Thanksgiving ritual. Bottled water. Ice. Ballpark hot dogs. Airplane pretzels. Movie theater popcorn.

Food can also establish group identity apart from the mainstream. Think of the many factions of vegan, vegetarian, paleo, grain-free and carnivore dieters who use food to express a political position. Also, of course, religious dietary proscriptions have worried scholars for centuries so that Jews, Muslims and Christians may never share a meal.

There is no evidence that Haitians are stealing and eating pet cats and dogs. There is evidence, however, that racists have long twisted dietary rules to divide people and dehumanize immigrants. Trump told a lie to draw a line between Americans and others who allegedly eat the animals Americans love.

The legend of delicious pets

The myth of eating pets traces back to old legends in Europe, Australia and the United States that “immigrants are stealing our cats and dogs for their dinner tables or to serve in ethnic restaurants,” writes the folklorist Jan Harold Brunvand.

Two of the most common food-based legends center on “Oriental restaurants serving dog (or cat) meat, and legends about Asian immigrants in the United States capturing and cooking people’s pets,” Brunvard writes.

By 1883, the legend was so well-established that the Chinese-American journalist Wong Chin Foo offered US$500 to anybody in New York for proof that Chinese people were eating cats or rats. No proof was found, but that didn’t stop the racist jokes or urban legends.

None of the many examples deserve retelling. But scholars, for example, have cited “sick jokes” such as a “new Vietnamese cookbook is titled 100 Ways to Wok Your Dog.”

Or as comedian Tessie Chua joked about her multiracial Chinese, Filipino and Irish identity in 1993 when she said, “That means I eat dog, but only if I can wash it down with Guinness Stout!”

In 1971, mainstream news outlets, including Reuters, reported an “outrageously silly urban legend” of a pet poodle named Rosa served at a Hong Kong restaurant, complete with chili sauce and bamboo shoots.

In 1980, Stockton, California, was seized by racist rumors of Vietnamese families stealing expensive purebred dogs for dinner.

As recently as 2005, the TV show “Curb Your Enthusiasm” showed wedding guests vomiting after being misinformed that they had eaten a German shepherd named Oscar, prepared by a Korean-American florist. “Oscar is bulgogi!,” Larry David cries.

Scholars calls these tropes a “nativist backlash” and “vehicle for anti-immigrant and especially anti-Asian sentiments in the U.S.”

A long history of food-based slurs

More precise, maybe, than the adage that “we are what we eat” is that we are what we won’t eat. Shunning our neighbor for their vile food – stinky, strange, unpalatable – is also decidedly an American tradition.

“Garlic eater” was at one time recognizable in the U.S. as an ethnic slur for Italian Americans in the early 20th century. The names “spaghetti bender” and “grape stomper” were also used, but “garlic eater” stuck because, as one scholar argued, “garlic served as an ‘olfactory signifier’” – a distinguishing odor – “for the alien who consumed it.”

So when far-right radical Laura Loomer tweeted in September 2024 that the White House “will smell like curry” if Kamala Harris becomes president, she was also using food to stoke racist fears.

Americans aren’t alone in doing this. Some Persians call Punjabis “dal khor,” meaning dal-eater, and some Romanians call Italians “macaronar,” meaning macaroni-eater. Both are slurs. Iranians have been known to call Arabs “malakh-khor,” or locust-eater, and Southern Italians sometimes call Northern Italians “polentoni,” or polenta-eater.

To an outsider, being called a lentil- or polenta-eater seems more like praise for a healthy diet than a racial epithet, but such are the vagaries of racism: People hate who they hate and justify it however possible.

Other examples of how food can distinguish communities abound. In the Amazon, the Parakanã people appreciate tapir meat but abhor monkey. The Arara people, their neighbors, feel the opposite. Both groups are disgusted by one another. Curry, garlic, tapir, polenta, lentils – it doesn’t matter what the nail is, but how the hammer hits.

Rumors with real-life consequences

Urban legends about food and racist rumors can have serious consequences. Earlier in 2024, a false rumor that a Laotian and Thai restaurant in Fresno, California, cooked pit bulls led to such vile harassment that the owner, David Rasavong, moved the restaurant to a new location.

After Trump repeated the myth during the debate that immigrants eat pets, Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, quickly became the target of bomb threats, forcing city buildings and schools to close. Members of the Haitian community have said they fear for their safety.

But there’s a more hopeful side to the issue of food being used as a way to divide or unite people, too. The Latin origins for the words company and companionship mean the people we share our bread with.

Garlic is now as central to American cuisine as apple pie. Nowadays, Americans are so much the better for the sushi, garlic and curry – and the diversity behind the deliciousness – that flavor American cuisine.

Adrienne Bitar does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.