Talk to any rhythm section player from a band, and they might start to use a number of adjectives to describe a performance. One word that often enters the musical vernacular is ‘groove’, but what is it, and how do you get some?

The truth is, in its most desirable form, groove is an incredibly complex business, and one that takes many years of instrumental practice and listening to past-masters.

As with so many aspects of commercial music, much of this extends outwardly from the drum kit, or if working in the realms production, your drum and percussion tracks.

It is the drums that you should be listening to when comp’ing instruments over the top; beginning with the bass, guitar, and keyboards, and extending to peripheral elements such as additional keyboards, a horn section, or even a vocal (and especially backing vocals!)

We can at least try to reduce groove to a lowest common denominator, and that’s ‘note displacement!’

The degree of displacement is informed by the style of music that you are playing. Music that is influenced by styles such as Latin or funk, use subtle and small degrees of displacement, but if you are playing a full on blues shuffle or a form of swung jazz, the displacement will be greater. But which notes do we displace?

This is fairly consistent. In music theory, we often talk about duplets, which is a pairing of small notes, such as a pair of quavers or semi-quavers (8th notes or 16th notes).

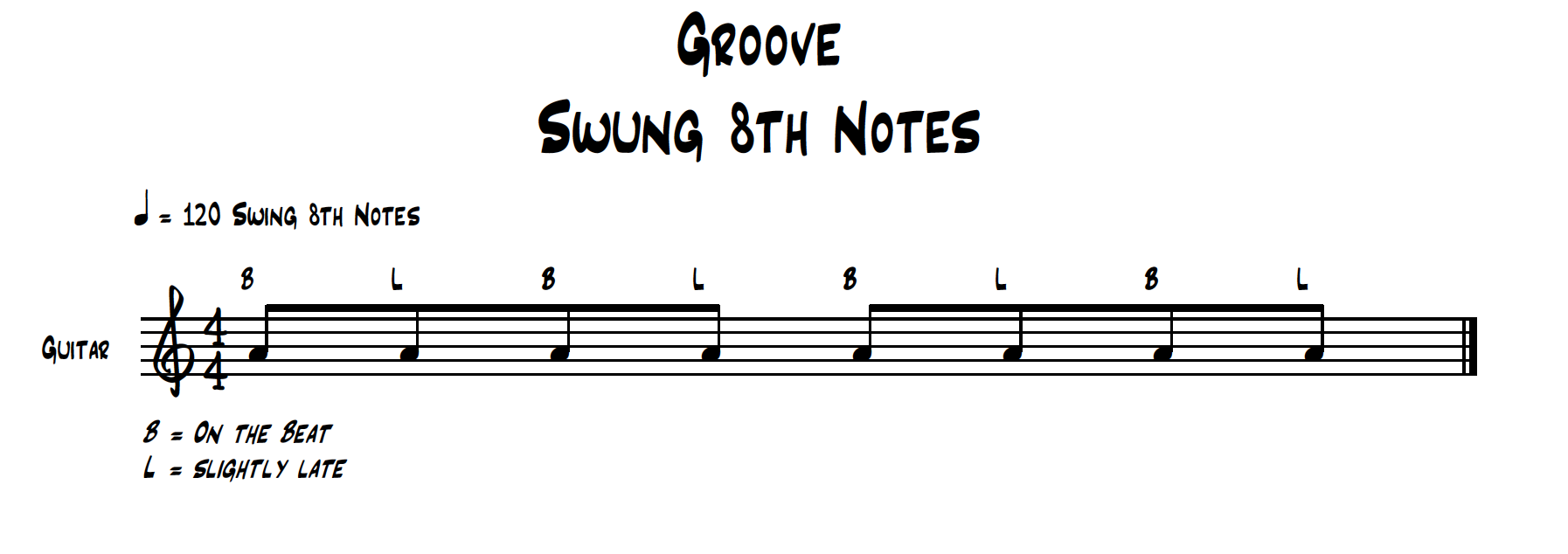

Regardless of which note value we are referring to, we leave the first note of each duplet on the beat, where it would normally be.

Then, we play the second beat, making the note subtly later, while ensuring that when we come around to the next duplet, we play the first note in the pairing, on time.

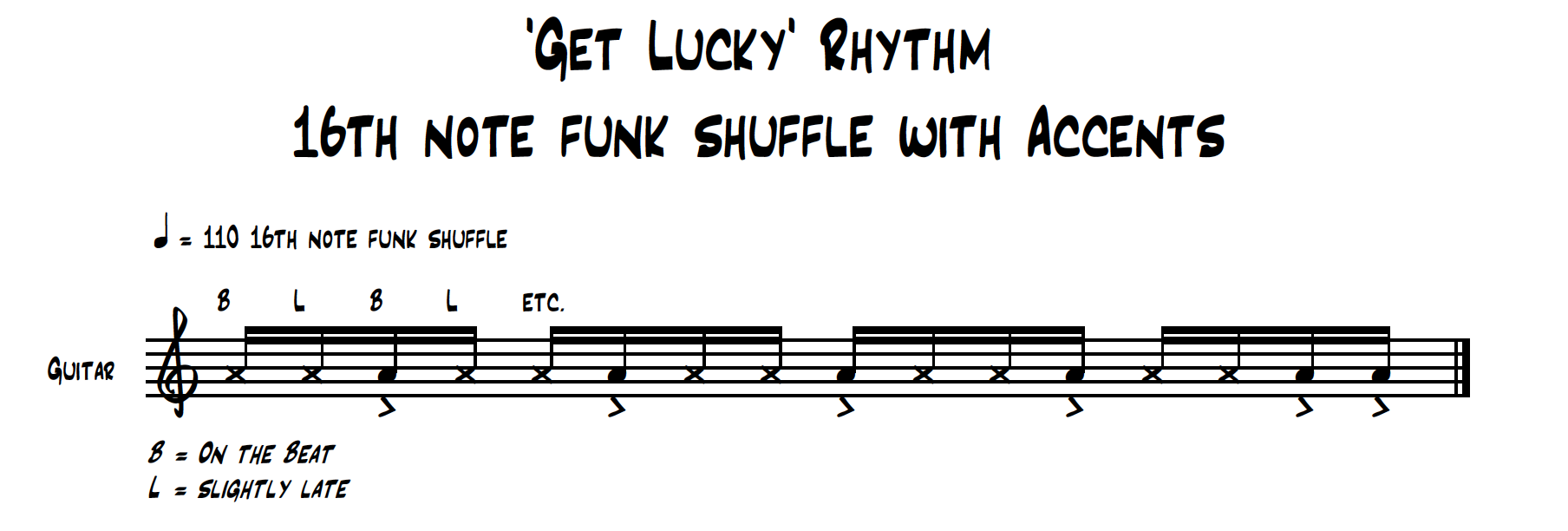

If we take a genre such as funk, you only have to listen to how to a master musician, such as guitarist Nile Rodgers, operates. His riff on Daft Punk's Get Lucky is a classic example of a funk riff, where the second of each 16th-note duplet is slightly delayed.

That's the displacement in action, but there is a little bit more to it than that! (There would be, wouldn’t there!)

You might also note that there is a complexity to the playing, where sometimes the chords are muted across the strings, whereas other times, there is a degree of accent.

Placing an accent on certain offbeat notes, such as the displaced note in a duplet, will also add to the groove and feel, although you may want to use this sparingly.

If you are an electronic musician, who works solely within a DAW, you may have noticed that within the quantise section of your software, there are levels of quantise that are described as 'swing', often with reference to either 8th notes or 16th notes.

If you try these, all your DAW is doing is delaying the second note of a pair of duplets, exactly as we have described here.

You can often apply a heavier degree of swing, which merely delays the second note even further. Take it too far, and it’ll be far too heavy, but keep it subtle, and it could make your track groove.

Groove is a very difficult thing to quantify, especially when dealing with a DAW, because it is subtle and complex and also organic and human.

But armed with a basic knowledge, you can at least set off in the right direction. Everybody needs a little bit of groove in their heart, right?