Roughly 48 hours after British athlete Keely Hodgkinson secured her first Olympic victory, in the women’s 800m final at Paris 2024, Nike was already celebrating in full bloom at its London flagship store, Nike Town, on buzzy Oxford Street. I witnessed it firsthand: a glass vitrine paraded a replica of Hodgkinson’s winning sneaker (signed by herself), complete with the time stamp of her gold-worthy race and an aerial shot of the finish line – let’s not forget the sprawling red and black LED screen column reminding us that ‘all-time greats don’t stop at gold’.

Are we even surprised? Of course not. Nike is both the master and student when it comes to its unrelenting encouragement to ‘Just do it’. Over the past 50 years, the sportswear giant’s evolutionary and revolutionary creative telescope rests in a simple truth: ‘to invite everybody – and every body – to experience sport for themselves’. For the grassroots startup turned global phenomenon (valued at just under 30 billion USD as of 2024), if you have a body, then you’re an athlete, and it’s via an unwavering commitment to design that the brand embraces the endless pursuit of athletic betterment in all its forms; no garment or sneaker comes out from pure instinct.

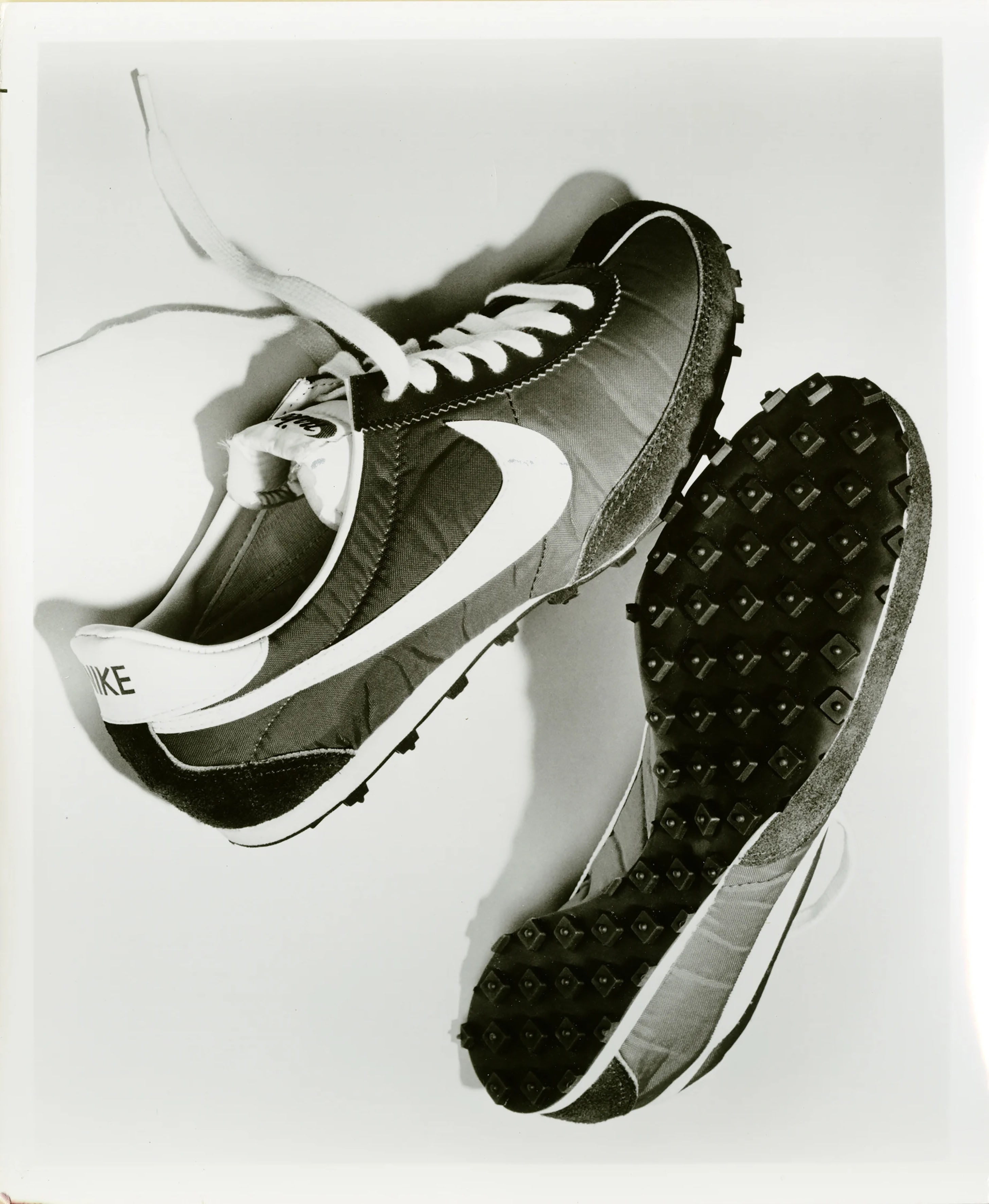

From the battered Air Force 1 kicks most teenagers wear to school to the Nike Zoom Victory 2 silhouette in which Hodgkinson won Olympic gold, every Nike product arises from years of ‘tinkering, adjusting, testing and refining’. As cited in the company’s 2023 design manifesto, No Finish Line: ‘Each successive product charts a new point on a never-ending journey forward.’ This was the ethos its co-founder and University of Oregon track coach Bill Bowerman pushed forward from the early days – he notably developed the label’s fabled Waffle sole using a kitchen iron at home.

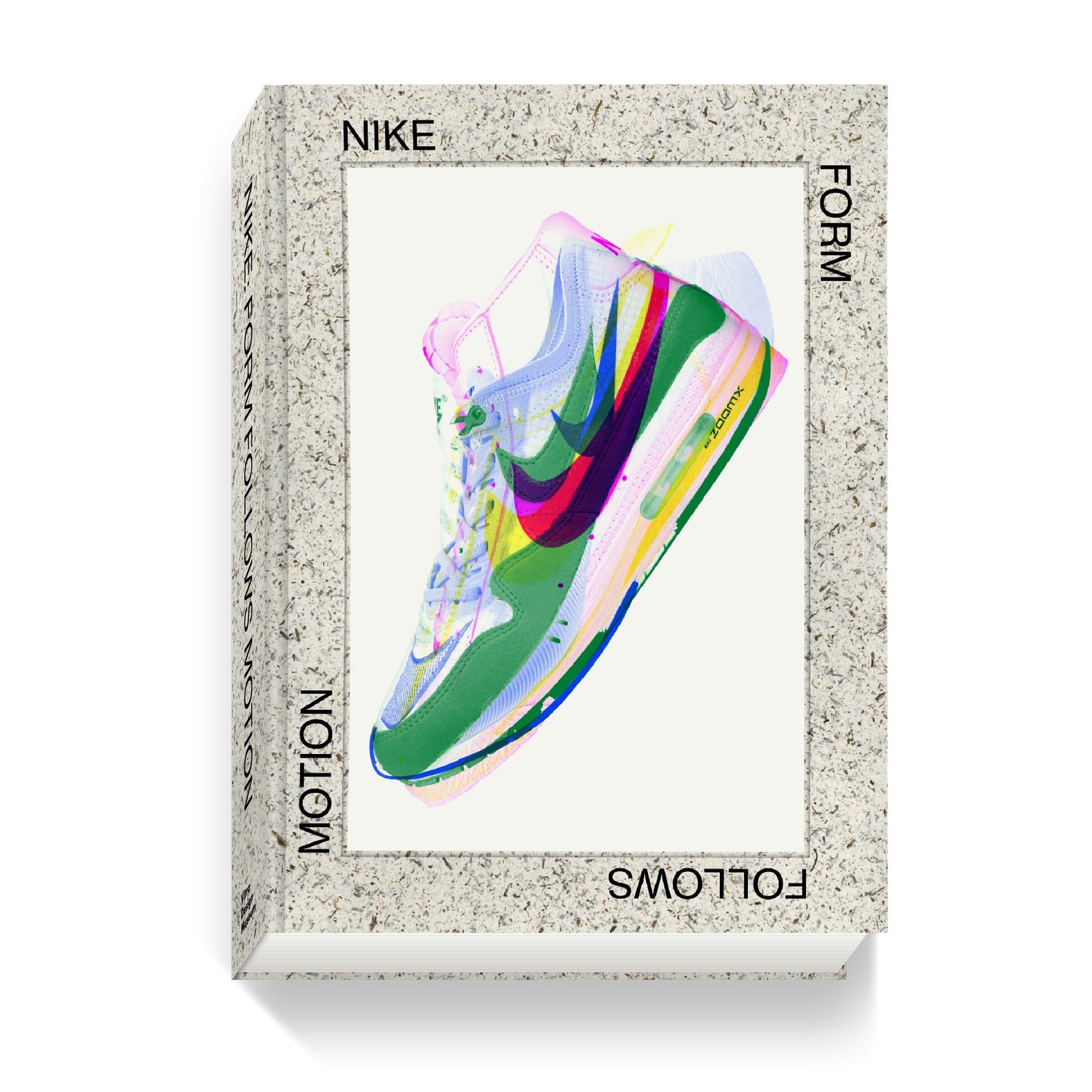

Tour ‘Nike: Form Follows Motion’ at the Vitra Design Museum

Across technology, performance, sports and pop culture, Nike’s presence is so ubiquitous that the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany, hosting the first major exhibition dedicated to the American behemoth may come as a surprise. Mateo Kries, director of the Vitra Design Museum, tells Wallpaper*: ‘It is a general phenomenon that design topics have taken very long to enter the museum world. During the past decade, there have been major exhibitions about some leading fashion houses, but to make an exhibition about a brand like Nike is yet another level. The brand’s design archive is an incredible treasure trove; we were lucky to come across it.’

‘Nike: Form Follows Motion’ traces five decades of the brand’s culture of design and innovation through the lens of athletes, designers, scientists and the wider community, with examples sourced from the Nike Design Archive (DNA), which consists of over 200,000 samples. As Kries emphasises: ‘There is not such a big difference between Nasa engineer Frank Rudy, who developed the original Air technology for more than a decade, and an athlete wearing Nike: both are pursuing a dream with great energy and determination.’ Of course, the question of what makes Nike Nike doesn’t have a straightforward answer, which is why the exhibition follows four chronological sections. The first, ‘Track’, delves into the brand archive’s earliest holdings: from hands-on marketing campaigns to early-day stories.

'There is not such a big difference between Nasa engineer Frank Rudy, who developed the original Air technology for more than a decade, and an athlete wearing Nike: both are pursuing a dream with great energy and determination.'

Mateo Kries, director of the Vitra Design Museum

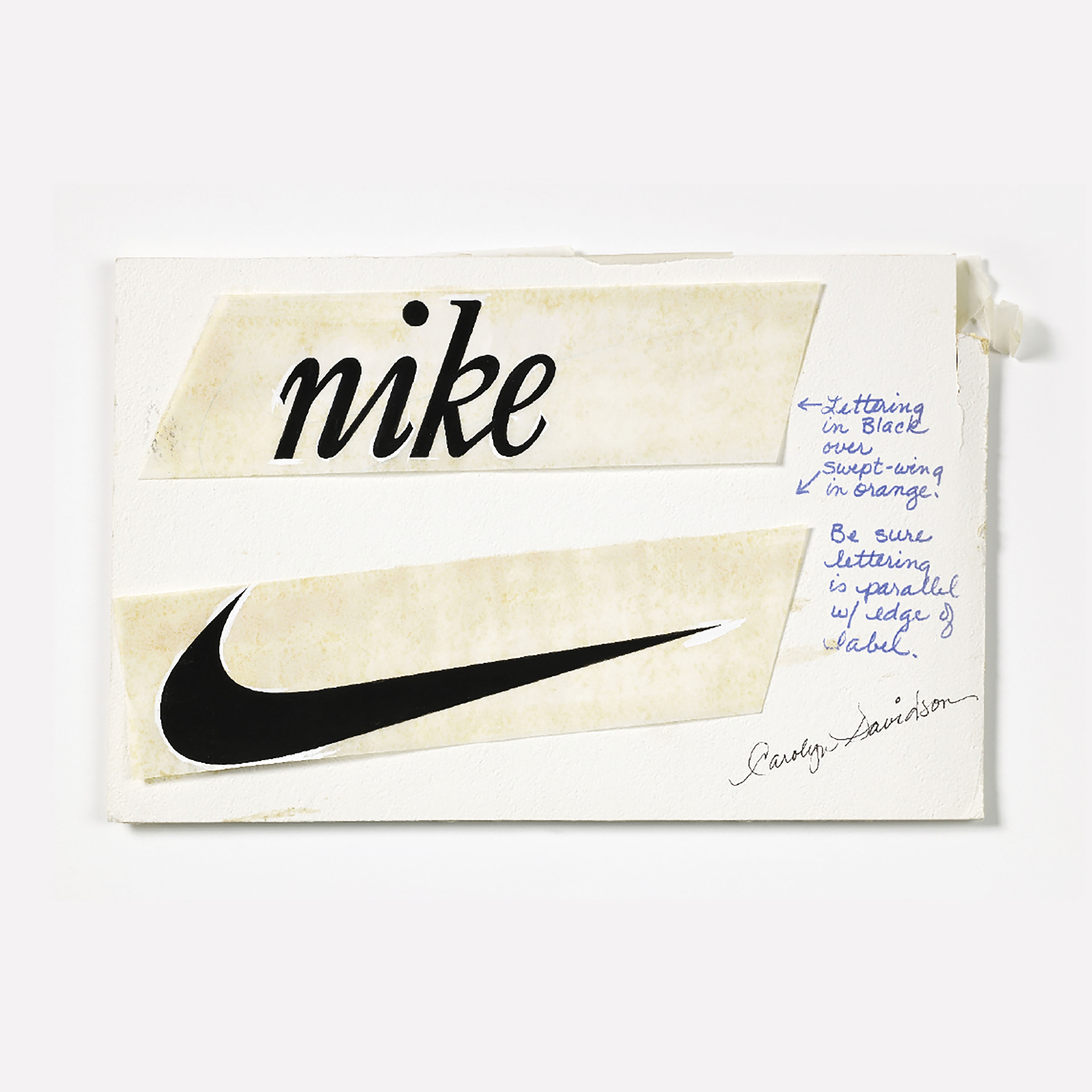

It was 1972 when American graphic designer Carolyn Davidson developed the Swoosh for Nike’s co-founders Phil Knight and Bowerman – today, one of the most recognisable logos in the world. Kries smiles at the idea that the logo itself could be the topic of a whole new exhibition: ‘It is one of the first logos that is purely abstract, which means not derived from any word or any figurative image (like an apple).’ A paragon of design perfection, the two overlaid curves with an elegant tip showing upwards elegantly express the idea of speed and movement. ‘It is also remarkable that the logo has remained unchanged over several decades, which is rare in our world of accelerated trends and images.’

‘It is one of the first logos that is purely abstract, which means not derived from any word or any figurative image (like an apple).’

Mateo Kries, director of the Vitra Design Museum

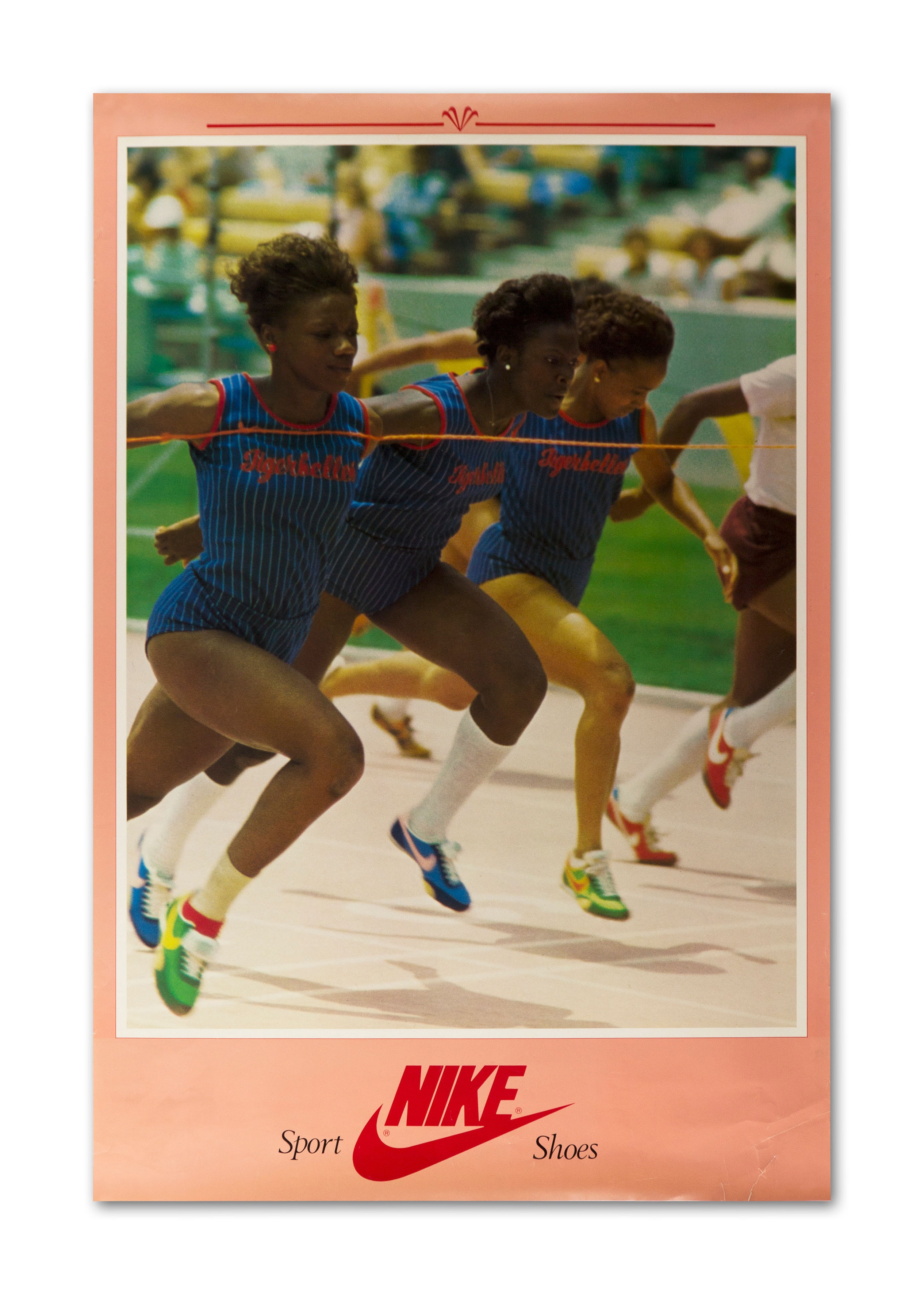

Glenn Adamson, curator of the exhibition and curator-at-large at the Vitra Design Museum, recounts a story from Nike’s early days: the Tennessee State Tigerbelles, a record-breaking relay team from a historically Black university that Nike endorsed in the 1970s: ‘The four runners – Deborah Jones, Brenda Morehead, Chandra Cheeseborough and Ernestine Davis – set a world record in the indoor 880 relay in 1978; this was an emblematic moment in the Civil Rights era and a precursor to the better-known relationships that Nike would develop with Black athletes in the 1980s and later.’

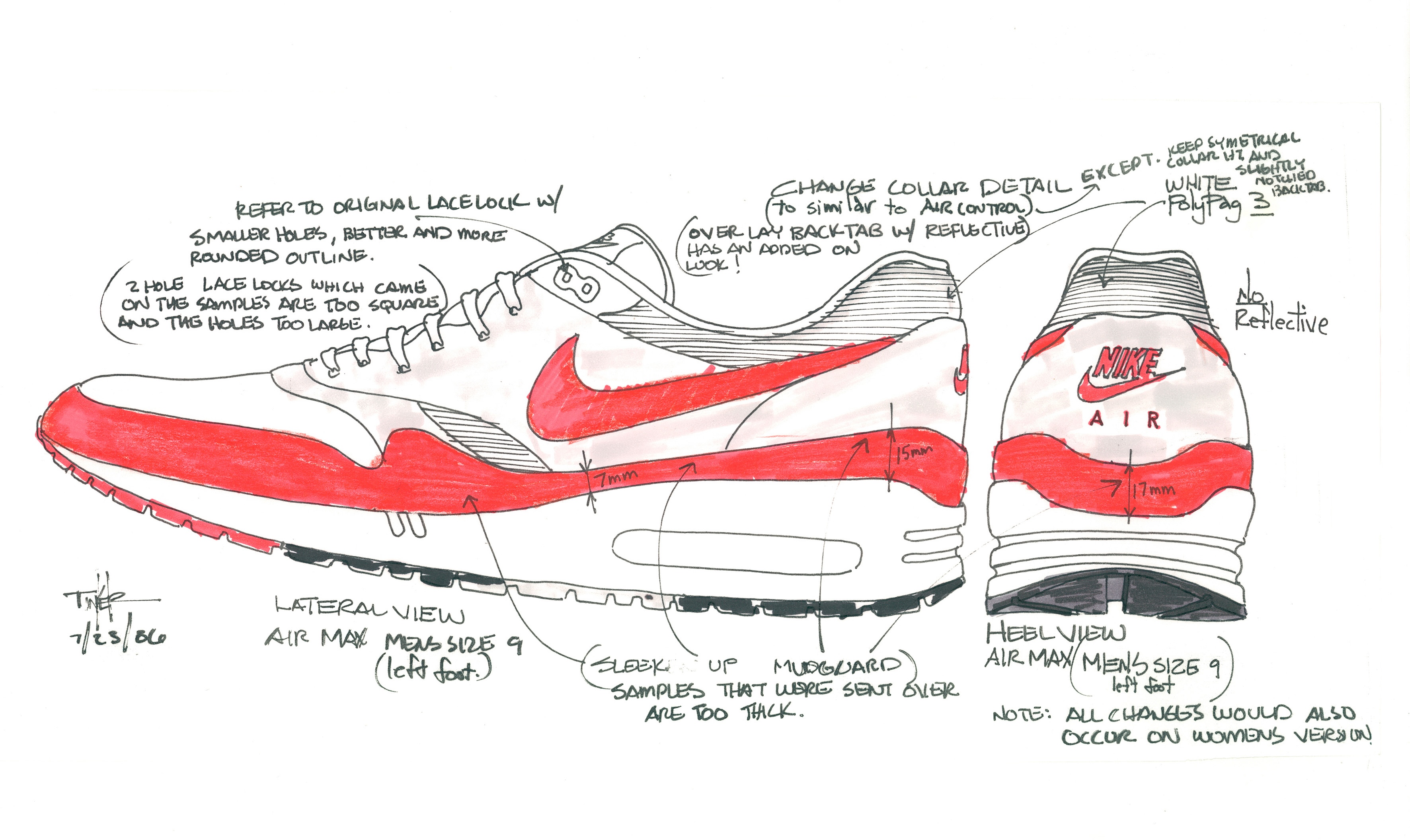

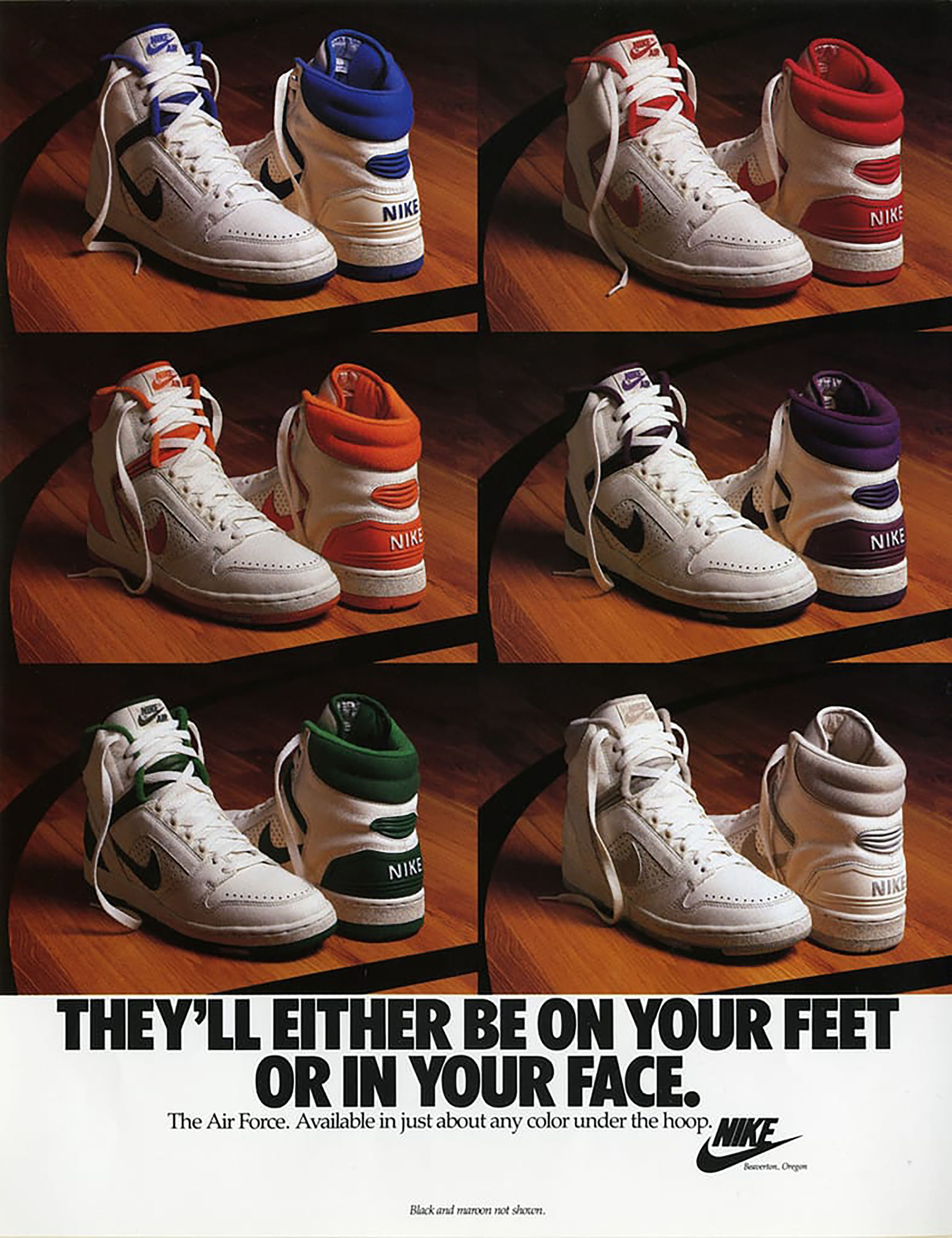

From its beginnings in the track-and-field scene, the company evolved into a national and, eventually, global powerhouse. The exhibition’s second chapter, ‘Air’, highlights the transformative 1980s when Nike truly took flight, propelled by strategic sponsorships of athletes across various sports. A pivotal moment came in 1984 with the launch of the first Air Jordan shoe, created for rookie Michael Jordan during his time with the Chicago Bulls, marking Nike’s entry into the basketball arena. This success paved the way for expansion into other categories like tennis, global football and skateboarding. The legendary Air Max 1 – for which in-house designer Tinker Hatfield got inspiration from Paris’ Centre Pompidou – also emerged during this era, ushering in a new chapter in the company’s design legacy.

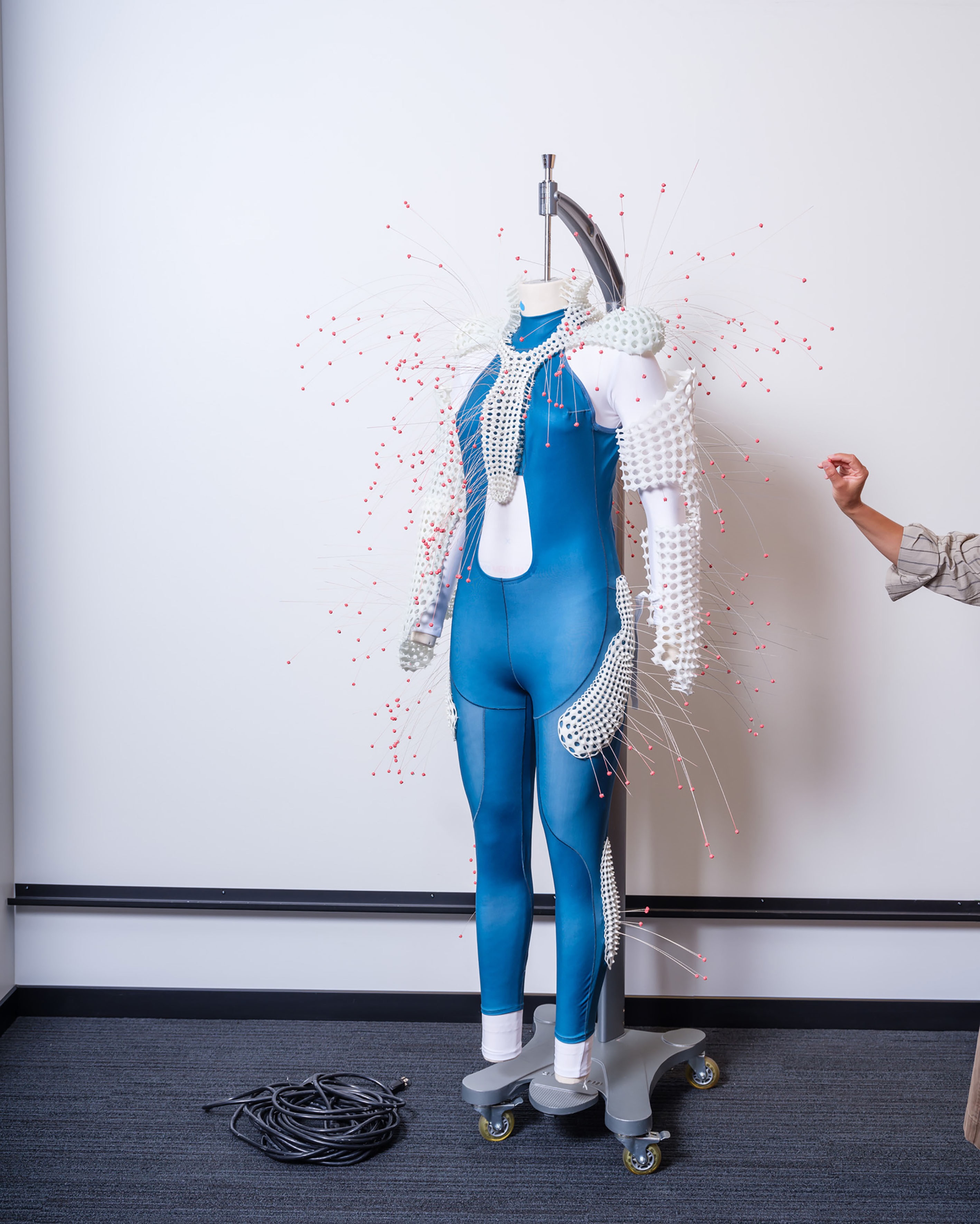

The third space, ‘Sensation’, delves into the research and development that shapes Nike’s design culture, highlighting the Nike Sport Research Lab in Beaverton, Oregon. Founded in 1980, this facility is among the largest and most advanced in the world for studying human movement, with many of its findings directly influencing the products we see on shelves. Adamson explains, ‘There, it’s not just about the feel of the materials or structure –though that’s certainly important – but also how a shoe or garment responds to athletes of varying body types, skill levels and needs.’ The exhibition looks at examples, such as the Alphafly series, engineered to break the two-hour marathon barrier, a feat ultimately achieved by Eliud Kipchoge, or the process behind shoes tailored for elite athletes like LeBron James, exemplifying a highly detailed ergonomic approach to design development.

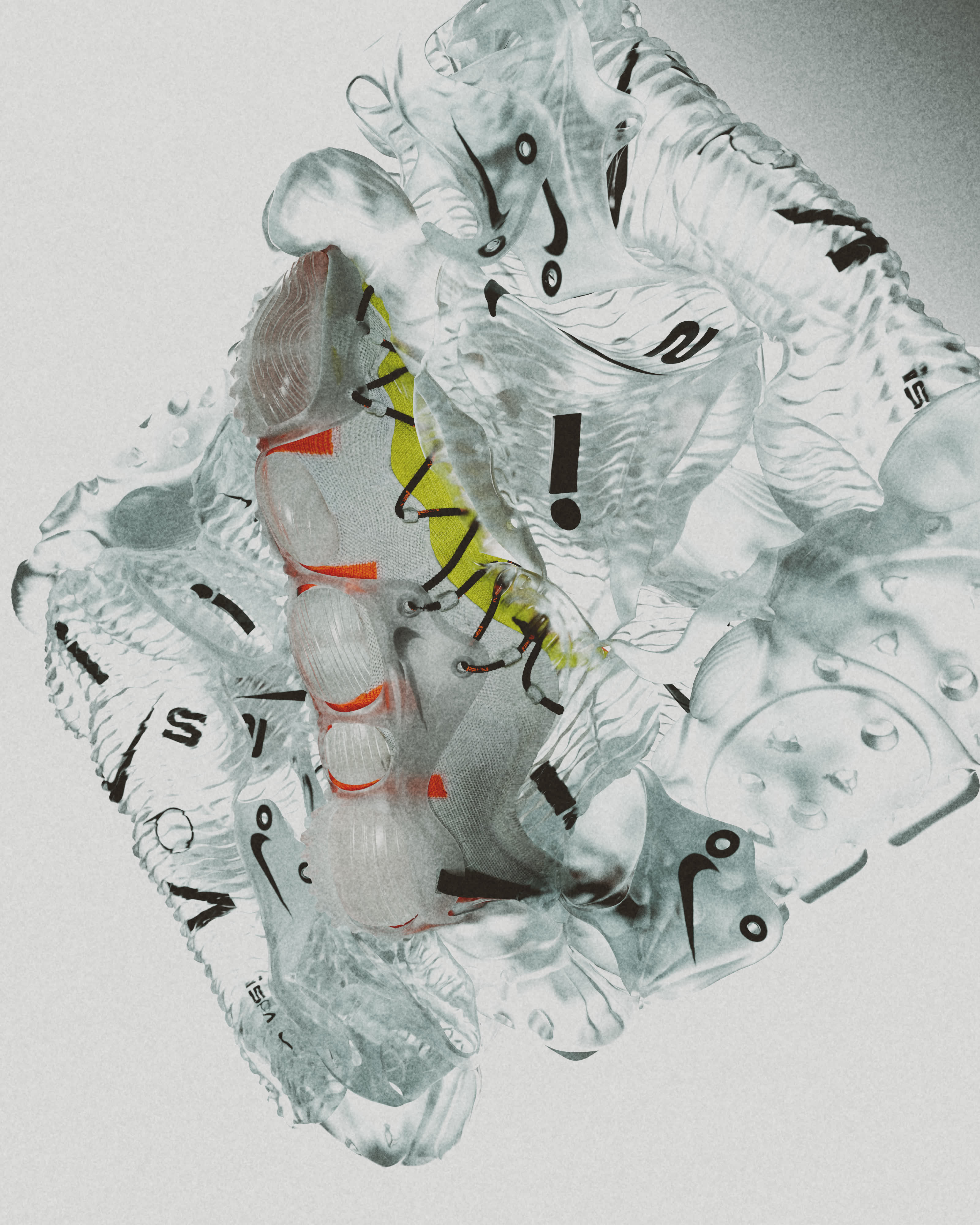

Nike’s design for sustainability is also touched upon, an integral component of the Swoosh’s creative process since the early 2000s. A topic often scrutinised, Kries notes the ambition for the exhibition was to give clear examples of green initiatives and inventions at Nike: ‘We present facts and examples to demonstrate the serious research and work behind Nike. Ultimately, it’s up to the audience to decide.’ This approach allows visitors to explore the brand’s composite material, Grind, made from the soles of old sneakers, and discover Flyknit technology, a digital knitting method that significantly reduces waste during production – most notably seen in the ISPA Link Axis silhouette.

The final chapter, ‘Relation’, acts as a fitting coda that encapsulates the essence of the Nike universe: exploring collaborations with a diverse array of external designers (think Marc Newson, Comme des Garçons and Virgil Abloh), athletes, musicians and other community-based initiatives that reflect the brand’s influential role in both popular and counter cultures. Reflecting on pivotal moments, Adamson recalls when American soccer player Brandi Chastain unveiled a Nike-developed sports bra during her 1999 championship celebration: ‘This was an encouragement for many women to request sports equipment adapted to their specific needs.’

For the sneakerheads eager to explore footwear rarities up close, Adamson promises two sections sure to captivate, including a prototype of the aforementioned Bowerman’s Waffle trainer. ‘These objects rarely leave the Nike campus, if ever, so having them in the exhibition is such an exciting opportunity.’ It’s the final room that heralds some never-before-seen highlights, such as a special never-released edition Air Force 1 designed to accompany American rapper Nelly’s 2002 album ‘Nellyville’; a 2018 Air Span created as a tribute to British blogger Gary Warnett (with only 40 pairs made); and shoes made back in 1982 for Elton John and Donna Summer.

‘Nike: Form Follows Motion’ will be on display at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany until 4 May 2025, and it’s set to travel to other international museums in the future. For more information, visit design-museum.de