Nichelle Nichols, an actor whose role as the communications chief Uhura in the original Star Trek franchise in the 1960s helped break ground on TV by showing a Black woman in a position of authority and who shared with co-star William Shatner one of the first interracial kisses on American prime-time television, has died aged 89.

Nichols, a statuesque dancer and nightclub chanteuse, had a few acting credits when she was cast in Star Trek. She said she viewed the TV series as a “nice steppingstone” to Broadway stardom, hardly anticipating that a low-tech science-fiction show would become a cultural touchstone and bring her enduring recognition.

Star Trek was barrier-breaking in many ways. While other network programmes of the era offered domestic witches and talking horses, Star Trek delivered allegorical tales about violence, prejudice and war – the roiling social issues of the era – in the guise of a 23rd-century intergalactic adventure. The show featured Black and Asian cast members in supporting but nonetheless visible, non-stereotypical roles.

Nichols worked with series creator Gene Roddenberry, her onetime lover, to imbue Uhura with authority – a striking departure for a Black TV actress when Star Trek debuted on NBC in 1966. Actor Whoopi Goldberg often said that when she saw Star Trek as an adolescent, she screamed to her family, “Come quick, come quick. There's a Black lady on television and she ain’t no maid!”

On the bridge of the starship Enterprise, in a red minidress that permitted her to flaunt her dancer’s legs, Nichols stood out among the otherwise all-male officers. Uhura was presented matter-of-factly, exemplifying a hopeful future when Blacks would enjoy full equality.

The show received middling reviews and ratings and was cancelled after three seasons, but it became a TV mainstay in syndication. An animated Star Trek aired in the early 1970s, with Nichols voicing Uhura. Communities of fans known as “Trekkies” or “Trekkers” soon burst forth at large-scale conventions where they dressed in character.

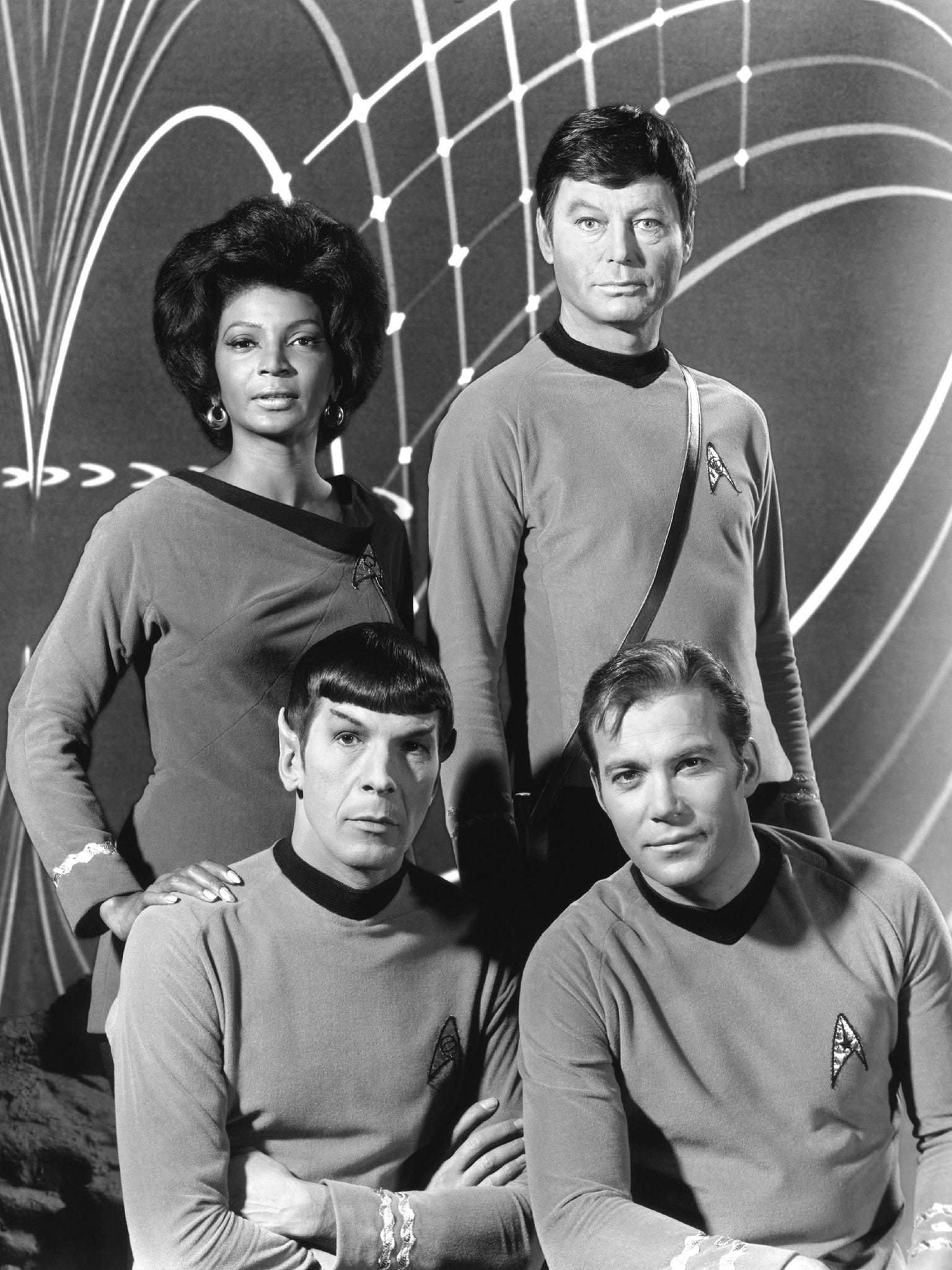

Nichols reprised Uhura, promoted from lieutenant to commander, in six feature films between 1979 and 1991 that helped make Star Trek a juggernaut. She was joined by much of the original cast, which included Shatner as the heroic captain, James T Kirk, Leonard Nimoy as the half-human, half-Vulcan science officer Spock, DeForest Kelley as the acerbic Dr McCoy, George Takei as the Enterprise’s helmsman Sulu, James Doohan as the chief engineer Scotty, and Walter Koenig as the navigator Chekov.

Nichols said Roddenberry allowed her to name Uhura, which she said was a feminised version of a Swahili word for “freedom”. She envisioned her character as a renowned linguist who, from a blinking console on the bridge, presides over a hidden communications staff in the spaceship’s bowels.

But by the end of the first season, she said, her role had been reduced to little more than a “glorified telephone operator in space”, remembered for her oft-quoted line to the captain, “Hailing frequencies open, sir.”

In her 1994 memoir, Beyond Uhura, she said that, during filming, her lines and those of other supporting actors were routinely cut. She blamed Shatner, whom she called an “insensitive hurtful egotist” who used his star billing to hog the spotlight. She also said studio personnel tried to undermine her contract negotiating power by hiding her ample fan mail.

Years later, Nichols claimed in interviews that she had threatened to quit during the first season but reconsidered after meeting civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr at an NAACP fundraiser. She said he introduced himself as a fan and grew visibly horrified when she explained her desire to abandon her role, one of the few non-servile parts for Blacks on television.

“Because of Martin,” she told Entertainment Tonight, “I looked at work differently. There was something more than just a job.”

Her most prominent Star Trek moment came in a 1968 episode, “Plato’s Stepchildren,” about a group of “superior” beings who use mind control to make the visiting Enterprise crew submit to their will. They force Kirk and Uhura, platonic colleagues, to kiss.

In later decades, Nichols and Shatner touted the smooch as a landmark event that was highly controversial within the network. It garnered almost no public attention at the time, perhaps because of the show’s tepid ratings but also because Hollywood films had already broken such taboos. A year before the Star Trek episode, NBC had aired Nancy Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jr giving each other a peck on the lips during a TV special.

Star Trek went off the air in 1969, but Nichols’s continued association with Uhura at Trekkie conventions led to a Nasa contract in 1977 to help recruit women and minorities to the nascent Space Shuttle astronaut corps.

Nasa historians said its recruiting drive – the first since 1969 – had many prongs, and Nichols’s specific impact as a roving ambassador was modest. But the astronaut class of 1978 had six women, three Black men and one Asian-American man among the 35 chosen.

Grace Dell Nichols, the daughter of a chemist and a homemaker, was born in Illinois on 28 December 1932, and grew up in Chicago.

After studying classical ballet and Afro-Cuban dance, she made her professional debut at 14 at the College Inn, a high society Chicago supper club. Her performance, in a tribute to the pioneering Black dancer Katherine Dunham, reputedly impressed bandleader Duke Ellington, who was in the audience. A few years later, newly re-christened Nichelle, she briefly appeared in his travelling show as a dancer and singer.

At 18, she married Foster Johnson, a tap dancer 15 years her senior. They had a son before divorcing. As a single mother, Nichols continued working the grind of the nightclub circuit.

In the late 1950s, she moved to Los Angeles and entered a cultural milieu that included Pearl Bailey, Sidney Poitier and Sammy Davis Jr, with whom she had what she described as a “short, stormy, exciting” affair. She landed an uncredited role in director Otto Preminger’s film version of Porgy and Bess (1959) and assisted her then-boyfriend, actor and director Frank Silvera, in his theatrical stagings.

In 1963, she won a guest role on The Lieutenant, an NBC military drama created by Roddenberry. She began an affair with Roddenberry, who was married, but broke things off when she discovered he was also seriously involved with actress Majel Barrett. “I could not be the other woman to the other woman,” she wrote in Beyond Uhura. (Roddenberry later married Barrett, who played a nurse on Star Trek.)

Nichols’s second marriage, to songwriter and arranger Duke Mondy, ended in divorce. Besides her son, Kyle Johnson, an actor who starred in writer-director Gordon Parks’s 1969 film The Learning Tree, a complete list of survivors was not immediately available.

After her role on Star Trek, Nichols played a hard-boiled madame opposite Isaac Hayes in the 1974 blacksploitation film Truck Turner. For many years, she performed a one-woman show honouring Black entertainers such as Lena Horne, Eartha Kitt and Leontyne Price. She also was credited as co-author of two science-fiction novels featuring a heroine named Saturna.

Nichols did not appear in director JJ Abrams’s Star Trek film reboot that included actress Zoe Saldana as Uhura. But she gamely continued to promote the franchise and spoke with candour about her part in a role that eclipsed all her others.

“If you’ve got to be typecast,” Nichols told the UPI news service, “at least it’s someone with dignity.”

Nichelle Nichols, actor, born 28 December 1932, died 30 July 2022

© The Washington Post