Exiled Nicaraguan economist Javier Álvarez received terrible news this week: his wife, daughter and son-in-law, jailed three weeks ago by the government of President Daniel Ortega, had been formally charged with serious crimes back in Nicaragua.

Jeannine Horvilleur, 63, Ana Carolina Álvarez Horvilleur, 43, both of Nicaraguan and French nationality, as well as Ana Carolina’s husband, Félix Roiz, were not only detained to apply pressure on Álvarez who had fled to Costa Rica, but they were now facing serious prison time.

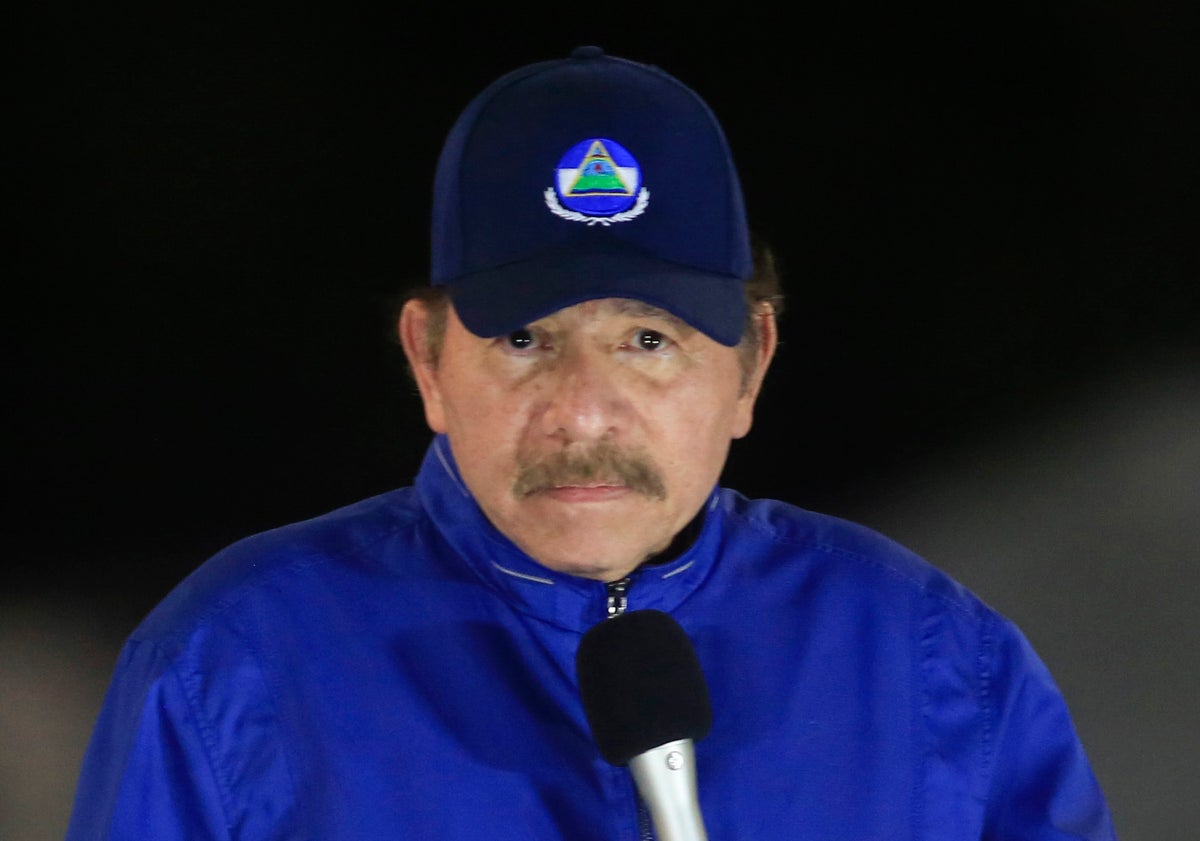

Ortega’s government has stepped up its persecution of political opponents. Apparently no longer satisfied by driving them into exile, it is now pursuing their relatives criminally.

Human rights organizations have accused the government of making relatives “hostages.” Tens of thousands of Nicaraguans have fled the country in the crackdown that followed massive street protests in April 2018. Dozens of others have been arrested and given lengthy prison sentences.

“When I found out Sunday that in the judicial system there was already a charge, I suffered one of the hardest blows,” said Álvarez, who opposes the government, but does not hold a leadership position in the opposition. “The world fell in on me.”

Last month, he had learned of their arrests shortly after he arrived in Costa Rica.

“That moment was extremely cruel, I in free country and free, and my family detained,” he said. He had hoped they would be interrogated and freed since none was involved in politics. His daughter and son-in-law manage a small business.

Two days after their arrest, the 67-year-old Álvarez received a message from the police, confirmed they were being held at the infamous El Chipote prison “and that they would not get out until I turned myself in.”

According to the nongovernmental Nicaragua Center for Human Rights, the case revealed “a new pattern of extortion kidnapping” by the government to leverage the capture or surrender of exiled opposition members. “They took them like hostages,” the organization said.

Similar to the case of Álvarez’s family, Freddy Martín Porras, brother of Dulce María Porras, a leader of UNAMOS, was arrested. Dulce María Porras, 71, has been living in exile in Costa Rica since authorities sought her in 2018.

“They are kidnapping our relatives because they can’t capture us,” Porras said. “This is a criminal act, typical of drug cartels.” She said her brother had participated in protests against the government, but for some time now had not been active politically and worked selling medicines.

Still, Freddy Martín Porras was also charged with spreading fake news and conspiring to damage national integrity.

Gabriel López Del Carmen was arrested Sept. 14 at his mother’s home. He and his mother were accused of conspiracy and an order was issued for her arrest.

“I had to protect myself outside the country because of the regime’s persecution, and when they didn’t find me in my house the police captured my son,” Andrea Margarita Del Carmen wrote on social media. “They know perfectly well that he has no tie to political activities.”

Lawyer Gonzalo Carrión with the human rights collective “Nicaragua Never Again,” based in Costa Rica, said the arrests of relatives are a “pattern of arbitrary and unconstitutional actions.”

On Tuesday, the government confirmed that the charges of spreading fake news and conspiring to damage the country’s integrity were also brought last month against four priests, two seminarians and a cameraman who had been staying with Rolando Álvarez, bishop of Matagalpa.

In Costa Rica, Javier Álvarez said he is living with “almost unmanageable anguish.”

“They are looking to increase the terror that they have imposed on citizens,” he said. “Now they transfer the supposed ‘blame’ or ‘crime’ to the intimate sphere, to the most precious which is the family ... to cause the greatest pain possible” on the opposition, he said.

Álvarez admits that his first thought was to turn himself in, but that friends and lawyers told him there was no guarantee his relatives would be released. He has filed reports with the French government, humanitarian organizations, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the United Nations Human Rights Office.

“They have left me without family,” he said.