In 1997, Tony Blair’s election “pledge card” included a promise to cut NHS waiting lists, then totalling 1.16 million. Keir Starmer’s “first steps for change” include a similar pledge to cut waiting times, but his task is on a different scale, with 7.5 million people currently awaiting treatment. How did things get so bad?

Blair’s government eventually got waiting lists down with a combination of hard cash for hospitals and harder threats for their managers. After 13 years of Labour government and a global financial crisis, David Cameron’s Conservatives took over in 2010, but needed support from the Liberal Democrats to form a governing coalition that spent the next five years trimming the fat – and a big chunk of flesh and bone – from public services, including the NHS.

Between 2010 and 2024, the Conservative party remained in power but rarely seemed to be in control – constrained by a combination of coalition partners, party malcontents and international crises (some, such as Brexit, of its own making). Still, it has been the Conservative party’s five prime ministers and seven health secretaries who have had the greatest influence over the NHS over the past 14 years.

The first health secretary, Andrew Lansley, embarked on a bold set of structural reforms that he hoped would improve choice and competition but which simply confused everyone, making it difficult to see who was in charge of what. Subsequent health secretaries learned the lesson and settled for tinkering with the existing system while trying to keep the lid on spending.

There was an increasing focus on prevention, integrated care, local accountability and community-based care approaches. Mental health services were finally given “parity of esteem” (treated equally) with physical health services – at least on paper. And there was an attempt to expand digital health services and online consultations.

The government also did some distinctly un-Conservative things, including introducing a sugar tax to stem the rising tide of obesity and diabetes.

Conservative frugality was upturned by the COVID pandemic. Billions were lavished on a vaccination programme, which worked very effectively, and a personal protective equipment procurement programme, which did not. After the pandemic, the NHS faced a mountainous backlog of cases which it has to tackle with a knackered workforce under reimposed financial discipline.

Following this tumultuous period, a new health secretary will need to pick up the pieces of a largely still cherished, but battered, NHS. Here, we highlight some of the challenges they will face.

Challenge 1: spending

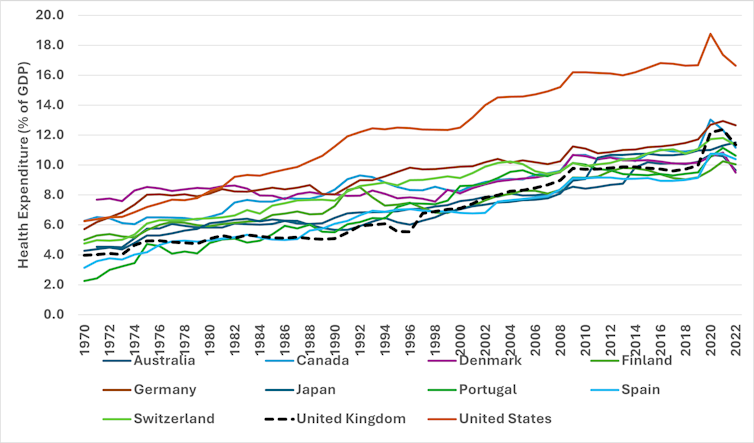

In 2002, Sir Derek Wanless recommended that the NHS budget should be increased from 4.2% to 5.1% a year to maintain its viability. The last Labour government exceeded this, increasing annual spending by an average of 5.5%, but growth was restricted to 1.1% between 2010 and 2015 and 2.8% up to 2023.

During the pandemic, the NHS received the biggest spending increase in its history, but this was emergency funding and was not sustained. Repeating the “prudence” of the incoming government in 1997, Labour has committed to constrained public service spending in the early stages of government, but to deliver the NHS workforce plan (a plan to increase the number of healthcare professionals) and improve the service in general, substantially higher spending may be needed.

Health spending as a percentage of GDP across the OECD, UK highlighted

Challenge 2: the NHS workforce

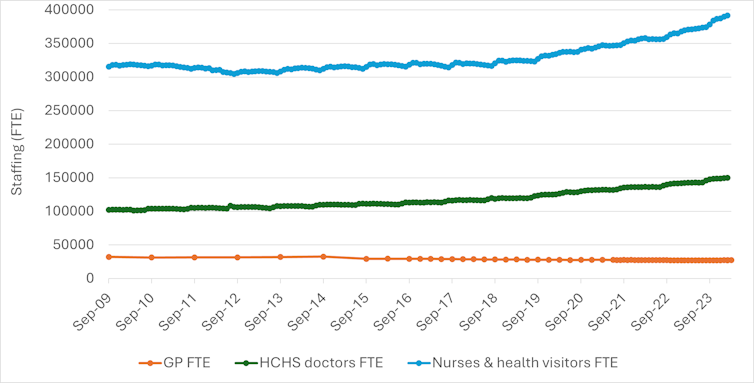

Healthcare is labour intensive, with limited potential for increasing productivity through technology. Hospital staff numbers have grown since 2010, but this appears not to have kept pace with demand, and full-time equivalent GP numbers have fallen.

Full-time equivalent medical and nursing staff, England

The government has offset the cost of increasing staff numbers by paying them less, with salaries falling by up to 10% in real terms, leading some of the worst affected to take repeated industrial action.

Challenge 3: waiting times

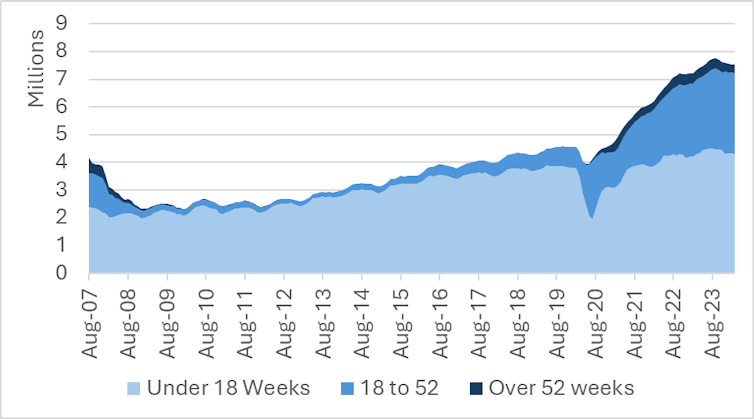

For the first few years under the Conservatives, Labour’s tight waiting time targets continued to be hit, but the headline target (92% of patients waiting no longer than 18 weeks) has not now been met since 2015.

Median waiting times are now almost three times higher than in 2010, and more than 300,000 people have waited more than a year for treatment. Emergency admissions have also been rising as the population has grown and aged.

Increasing numbers of older adults are being admitted to hospitals, and getting them out again is increasingly difficult, largely due to a lack of capacity in social care.

Consultant-led referral to treatment waiting times, England

Challenge 4: patient satisfaction

Public satisfaction with the NHS has been surveyed annually since the 1980s, and 2010 marked a high point, with 70% of respondents very or quite satisfied. Since then, and particularly since 2019, this figure has plummeted to 24%.

Satisfaction with GP services – traditionally very high – also dropped sharply between 2021 and 2022, and has not recovered.

Challenge 5: life and death

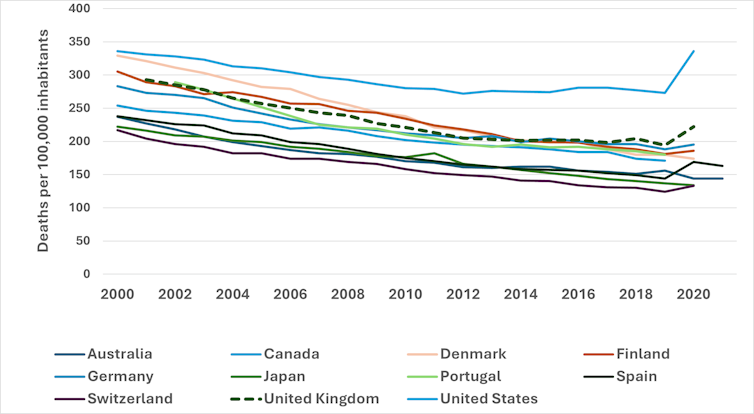

Deaths that are avoidable with timely and effective healthcare fell throughout the NHS’s history until around 2013, after which they hardly changed until COVID forced them back up.

Before COVID, rates of avoidable deaths in the UK were higher than in most comparable countries, with only the US having consistently worse figures.

International comparison of mortality rates from avoidable causes (UK and selected OECD countries)

Challenge 6: everything else

On top of all this, Labour must also address shortfalls and shortcomings in social care, mental health (particularly for children), maternity care, dentistry, health inequality, multiple long-term conditions, recruitment and retention, digital health, pharmaceutical costs and the rest of a depressingly long list.

Wes Streeting, the new Labour health secretary faces, a situation notably worse than that faced by Frank Dobson in 1997. A decade of austerity has left the NHS clinging on by its fingertips every winter and lacking the capacity to deal effectively with the shock of a pandemic and its aftermath.

The NHS continues to provide healthcare on a grand scale, but many staff and patients are suffering. Restoring the NHS may take as great an effort as creating it in the first place.

Tim Doran receives funding from the NIHR policy research programme to conduct responsive analysis for the Department of Health and Social Care, grant number NIHR 200702.

Karen Bloor receives funding from the NIHR policy research programme to conduct responsive analysis for the Department of Health and Social Care, grant number NIHR 200702.

Veronica Dale receives funding from the NIHR policy research programme to conduct responsive analysis for the Department of Health and Social Care, grant number NIHR 200702.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.