Most online images are just a right-click away from being in someone’s personal collection. They’re free, pretty much. So it’s tough for charities to fundraise with them. That is, until 2017 when non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, came along. Unlike regular pieces of digital media, NFTs can’t be so easily copied. And for as long as they have existed, there have been conservation charities using them for fundraising.

A cartoon drawing of a cat-turtle named Honu raised US$25,000 (£18,485) for ocean conservation charities in 2018. Rewilder is a non-profit organisation using NFT auctions to raise funds to buy land for reforestation. The charity claims to have raised US$241,700.

There have been various cartoon apes sold for US$850,000, with the money going to orangutan conservation charities. The most expensive NFT to date, a picture of some small grey balls, sold to multiple buyers for US$92 million in December 2021.

With many UK charities in dire straits, it’s no surprise some want a piece of the crypto action too.

Recently, WWF UK joined the NFT circus with its Tokens for Nature collection. But before the fundraiser had even started, the project sparked a backlash from environmentalists online who worried about its carbon footprint. Within just a few days, the sale was terminated.

The NFAs (or Non-Fungible Animals) project aimed to raise lots of money and awareness about endangered animals. The number of rare animal images available for sale corresponded to the estimated number left in the wild. There were 290 Giant ibis NFAs, for example. An ibis jpeg would have raised about US$400 through a single sale .

‘Eco-friendly’ NFTs?

According to one estimate, NFTs generate more carbon emissions than Singapore as a result of their energy consumption.

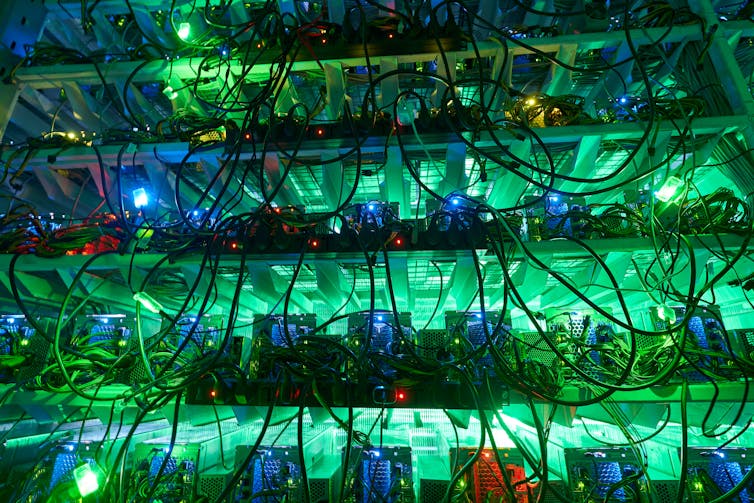

Most NFT creators use a technology called Ethereum, which is a blockchain system similar to Bitcoin that involves an energy-intensive computer function called mining. Specialist mining computers take turns validating transactions while guessing the combination of a long string of automatically generated digits. The computer that correctly guesses the combination first wins a reward paid in a cryptocurrency called ether.

Unlike regular NFTs though, WWF claimed that its NFAs were “eco-friendly”. In its sustainability statement, the charity suggested the sale of all 8,000 or so NFAs would have a similar carbon footprint to a pint of milk, or a half-dozen eggs. The reason for this negligible impact they claimed was a clever blockchain application called Polygon, which would have allowed WWF’s project fewer direct interactions with the Ethereum blockchain. WWF wouldn’t then need to take as much responsibility for its share of Ethereum’s monstrous carbon footprint.

So why the Twitter tantrums?

WWF’s assumption was a tricky one. That’s because Polygon depends on Ethereum contracts to carry out essential services, such as moving assets between Ethereum and Polygon and creating checkpoints between the two. According to Alex de Vries of the cryptocurrency monitoring website, Digiconomist, the footprint of WWF’s project was actually around 2,100 times more (12,600 eggs) than the estimate provided by the charity.

There are also second-order effects to consider. Ethereum’s carbon emissions are not related directly to the number of transactions occurring on the network. PoW mining is what gives Ethereum its dirty reputation. By pumping up the hype around NFT markets, the collection could drive up the price of Ethereum. This would encourage more PoW mining, increasing the network’s overall carbon footprint.

Initial buyers of NFAs would purchase them from WWF’s dedicated website. But buyers can relist their artwork on the popular NFT marketplace, OpenSea. OpenSea is currently the number one gas guzzler on the Ethereum network, responsible for nearly 20% of actions on the blockchain.

Blockchain backlash

WWF is not the first charity to reevaluate its position on crypto-giving. In 2021, Greenpeace stopped accepting bitcoin donations after seven years. Friends of the Earth soon followed. The WWF furore forced the wildlife charity, International Animal Rescue to park its NFT fundraising plans indefinitely. Internet nonprofits Mozilla and Wikipedia have also reconsidered their crypto-giving strategies on climate change grounds.

There are multiple NFT-friendly blockchains that don’t cause carbon headaches. Even so, research shows it’s difficult for charities to fundraise using NFTs without getting their hands dirty.

Charities should be mindful of growing public disapproval of blockchain projects. Some argue the technology is driven by predatory marketing tactics. Others claim blockchain is a platform for Ponzi schemes, grift, and multi-level-marketing arrangements. According to OpenSea, 80% of the NFTs minted through its site are spam, scams, or otherwise fraudulent.

Research also shows cryptocurrencies can restrict the work of conservation charities. In 2018, WWF partnered with blockchain developers, AidChain. To improve transparency in the donor tracking process, AidChain encouraged WWF to pay their service providers in a cryptocurrency called AidCoin. Using an Ethereum smart contract, donors could then track and manage how funds were spent.

Platforms like this can allow non-expert crypto donors to encode concrete conditions to their donations. Break the conditions – lose the funds. Great for the donor. Lousy for the charity’s conservation experts.

Before reacting to crypto-giving hype, conservation charities such as WWF need to do their homework. Animal jpegs and cryptocurrencies may seem a harmless way to fundraise. But mindlessly jumping on the blockchain bandwagon could tie their hands while longstanding donors take their support elsewhere.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Peter Howson currently receives funding from The British Academy.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.