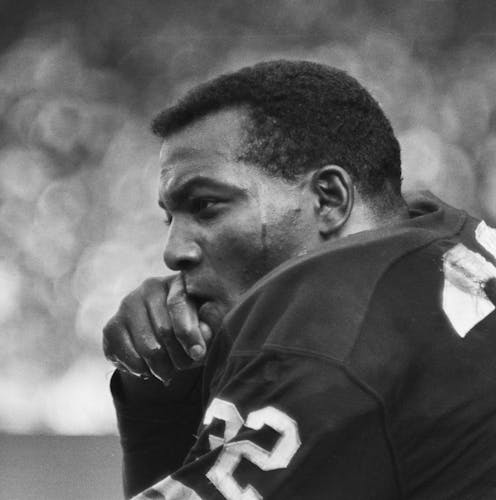

Throughout his celebrated life, Jim Brown was both praised for his community activism and vilified for his abuse of women.

But no one questions his incredible ability on the professional football field or his subsequent career in Hollywood during the racially tumultuous 1960s as one of the movie industry’s few Black male stars.

Considered by some sports analysts as the best football player in the history of the game, Brown became a Hall of Fame running back for the Cleveland Browns and used his celebrity status to fight for equal rights at a time when America’s racial divide was erupting throughout the Deep South.

From his fight against racial discrimination in the 1950s to his development of programs to end gang violence in the 1980s, Brown set an early standard for being more than just a gifted athlete.

As a scholar of African American Studies, it’s my belief that Brown’s death on May 19, 2023, at the age of 87 renews questions about the role that modern-day athletes could and should have on ongoing political and social debates.

Brown’s first public act of activism

Unlike later Black superstars such as O.J. Simpson, Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods, Brown was unafraid of potential financial losses and stood up for himself and, by extension, every Black man.

That boldness became clear when Brown walked away from football in 1966 to pursue another career as an actor in Hollywood, a decision prompted in part by the actions of Browns owner Art Modell.

Incensed that Brown was in England filming the movie “Dirty Dozen” instead of practicing with the team, Modell threatened to issue Brown daily fines of $100 until he returned.

Brown’s response was unequivocal.

In a letter to Modell, Brown wrote: “You must realize that both of us are men and that my manhood is just as important to me as yours is to you.”

His retirement in July 1966 from football was shocking.

As a young man who wanted to play professional football myself, I couldn’t understand why Brown walked away from the sport, voluntarily, at the age of 30 years old and at the peak of his career.

Little did I know at the time that his sudden retirement was a form of activism to be himself.

Brown said as much in his letter to Modell.

“This decision is final,” Brown wrote, “and is made only because of the future that I desire for myself, my family and, if not to sound corny, my race.”

I learned about Brown’s activism after I began to study sports as a scholar and came to realize how unique Brown was at the time and in comparison to other modern-day superstars who rarely jeopardize their livelihoods to protest racial inequality.

The Cleveland Summit

In June 1967, a year after his retirement, Brown organized what has come to be known as the Cleveland Summit, and it centered around Muhammad Ali and his refusal on religious grounds to join the U.S. military and fight in the Vietnam War.

For his refusal, Ali was stripped of his boxing titles and faced a fine of $10,000 and a five-year prison sentence. But he still rejected the government’s offer to restrict his military activity to only boosting the morale of U.S. troops by boxing in sparring matches on military bases and not serve combat duty.

To show Ali support and convince him to accept the government’s offer, Brown gathered a meeting of the greatest Black athletes of the day and several politicians, including Bill Russell, Lew Alcindor – later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar – Bobby Mitchell, Willie Davis and then-Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes.

“I felt with Ali taking the position he was taking, and with him losing the crown, and with the government coming at him with everything they had, that we as a body of prominent athletes could get the truth and stand behind Ali and give him the necessary support,” Brown told the (Cleveland) Plain Dealer in 2012.

In my view, not before, and certainly not since then, has there ever been a more significant gathering of athletes. Though the group failed to convince Ali to go against his religious beliefs, the meeting sent a powerful message that Black men were united and unafraid to support a Black man deemed an outcast by the U.S. government. Ali was later sent to prison.

“Everybody had taken a great risk at losing everything by meeting with him,” Brown told The Associated Press in 2016. “But what was so real was that we met for about five hours and Ali was asked every question that you could ask a person.”

Based on Ali’s genuine sincerity about his religious beliefs, Brown said the men became “a group of one” and decided “to back him all the way.”

A flawed presence

As a sports and entertainment attorney in Los Angeles, I often saw Brown at galas, some held at his home. Several years ago, I spent a day with him at Amer-I-can, the organization that he founded in the 1980s that is focused on gang members and formerly incarcerated men and women.

In both of those settings, Brown had universal respect, and to say he had presence does not do him justice.

Part of that respect was due to Brown’s public admission that he had flaws.

In his 1989 book “Out of Bounds,” he wrote regarding one domestic abuse case he was involved in: “The toughest thing I did to her was slap her. I have also slapped other women. … I don’t think any man should slap a woman.”

Clearly, some of Brown’s flaws were inexcusable. But for me, Brown offered a rare glimpse of a proud Black man who was willing to give up everything in order to stay true to his own principles.

The last time I saw Brown was during the 2023 Super Bowl festivities in Phoenix. Despite his frailty, crowded rooms still parted to make space for him.

No one invaded Jim Brown’s space without permission.

Kenneth L. Shropshire does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.