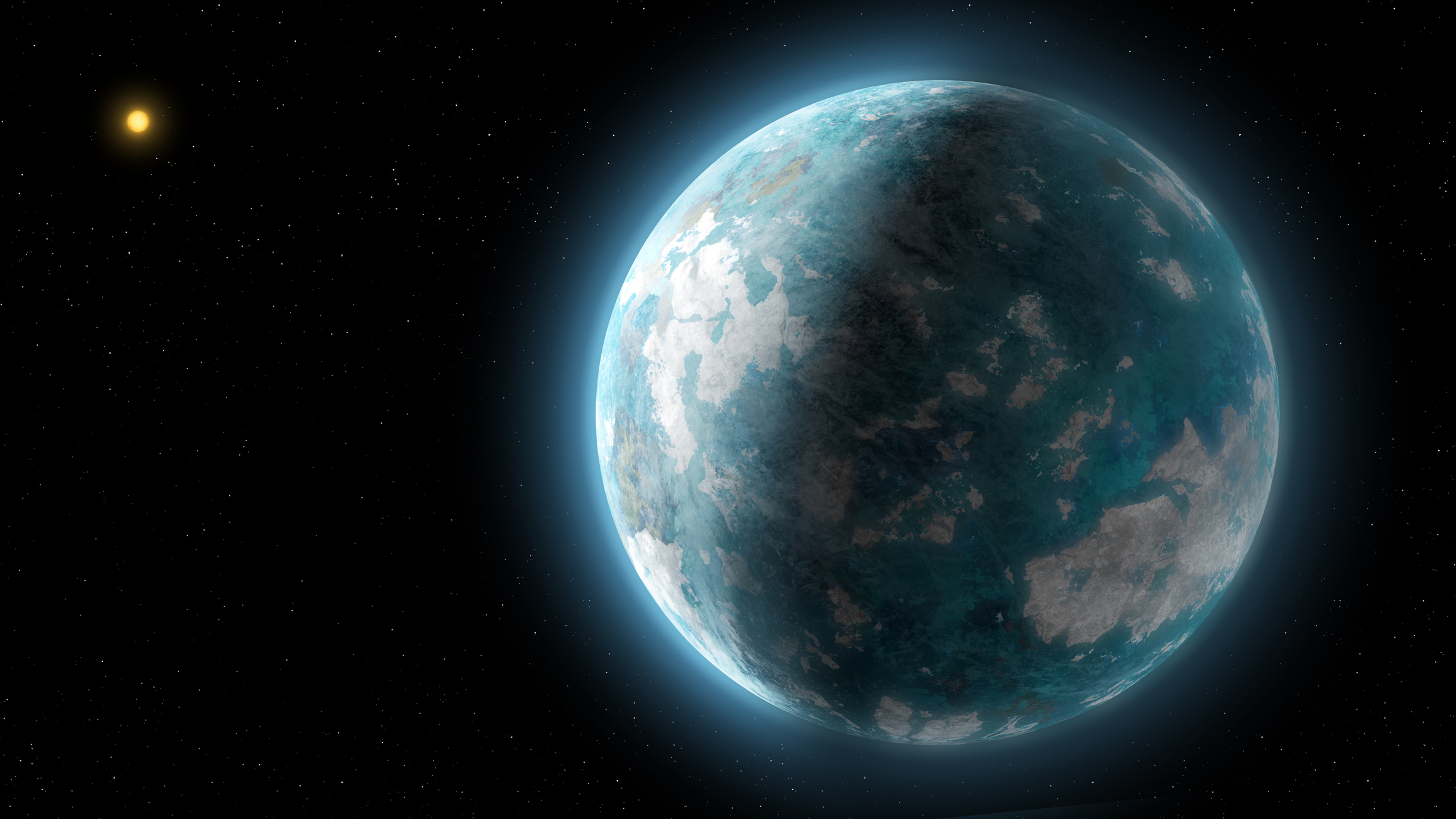

A super-Earth planet that dips in and out of its star's habitable zone has been discovered just 19.7 light-years away.

The planet, known as HD 20794d, gets farther out from its star than Mars is from the sun and, on the other end of its orbit, as close as Venus. Each orbit the planet begins out beyond the habitable zone, where it is too cold for liquid water, before passing right through the habitable zone to its inner edge where temperatures rise for a short period, before the planet moves back out again.

The planet provides a brilliant target for the next generation of telescopes to probe its atmosphere, and for scientists to test the extreme limits of planetary habitability. "Its luminosity and proximity make it an ideal candidate for future telescopes whose mission will be to observe the atmospheres of exoplanets directly," said Xavier Dumusque of the University of Geneva in a statement. Dumusque is a member of the team that discovered and characterized the new planet.

HD 20794d has a mass 6.6 times greater than Earth and was found by astronomers using the ESPRESSO and HARPS spectrographs on the European Southern Observatory's telescopes in Chile. These instruments measure what's termed 'radial velocity' — the amount by which a star wobbles around the center of mass that it shares with its planets. In general, the larger the wobble, the greater the mass of the planet. It's the wobbling star that has betrayed the existence of HD 20794d — astronomers have not directly observed HD 20794d, nor taken a picture of it or even seen it in transit yet.

The star in question, HD 20794 — also known as 82 Eridani — is a yellow G6-type star that's slightly dimmer and less massive than our own sun. It's also relatively bright in our night sky, shining at magnitude 4.3, which is bright enough to be seen with the unaided eye in the constellation of Eridanus, the River. In contrast, many of the stars hosting exoplanets are too faint to be seen with the naked eye, which marks out HD 20794 as something special.

Because of how close the HD 20794 system is to us, it has been well observed over the past 20 years and has a somewhat mixed history when it comes to exoplanets. HD 20794d orbits its star with two other super-Earth planets, designated b and c, which orbit their star every 18.3 and 89.6 days, respectively. These were discovered in 2011 by a team of Geneva astronomers including Dumusque. At the same time, the team found evidence for a third planet, with an orbital period of 40 days, but this was later shown to be false. Only now has the real third planet become apparent in the data.

"We analyzed the data for years, carefully eliminating sources of contamination," said Michael Cretignier of the University of Oxford. Cretignier was previously at Geneva, where he developed an algorithm called YARARA to carefully search the data and pick out an exoplanet's faint radial velocity signal from the background noise. YARARA proved vital in the effort to confirm HD 20974d as being real.

What's most remarkable about this new planet, however, is its orbit. While Johannes Kepler taught us that no planetary orbit is perfectly circular, most adhere to an orbit that is pretty close to being a circle. Some worlds, however, have more elongated orbits. The degree of elongation, known as eccentricity, is measured on a scale of 0 (for a perfect circle) to 1 (a hyperbola). Earth's orbital eccentricity is 0.017; Mars' is 0.055, and Mercury's is 0.206.

HD 20794d's orbit is more elongated than any planet in our solar system, with an eccentricity of 0.4. Its 647-day-long orbit is 40 days shorter than Mars, giving you an idea of where it is located in its planetary system. However, the large eccentricity means its orbit ranges from as far as 2 astronomical units (300 million km/186 million miles — i.e. twice the Earth–sun distance) from its star to as close as 0.75 AU (112 million km/69.7 million miles).

In the context of our solar system, Mars — on the outer edge of our habitable zone — orbits our sun at an average distance of 1.5 astronomical units (228 million km/141 million miles), while Venus, on the inner edge of the habitable zone, orbits at 0.72 astronomical units (108 million km/67 million miles) from our sun.

The climate on such a world must be beyond bizarre. Winters would be long and hard, and life might struggle to survive on a planet that spends most of its time frozen. Then spring would come, melting the ice, followed by a brief but intense summer when oceans might even begin to evaporate, only to precipitate back out as rain in autumn and snow in winter. Whether life could survive on such an extreme world is unknown.

On Earth, our seasons are driven by our planet's 23.4-degree tilt; for instance, northern summer occurs when our planet's northern hemisphere is tilted towards the sun. No matter the tilt of HD 20794d, its seasons are instead determined by how far it has progressed along its eccentric orbit. It is a remarkable planet.

The origins of such a large degree of eccentricity lie in the HD 20794d's distant past, Dumusque tells Space.com. "The eccentricity of planets are a remnant of planet–planet interactions during the early days of a planetary system," he says. Although the other two planets, b and c, do not have eccentric orbits, something may have perturbed the orbit of HD 20794d not long after it formed.

"For example, there could have been another giant planet in the early phase of formation," said Dumusque. "The giant planet could have influenced the orbit of planet d, and then that giant planet was ejected outside of the system."

The discovery of this exciting new world is detailed in Astronomy & Astrophysics.