It’s not often New Zealanders admit Australia is onto a good thing. Our long-running trans-Tasman rivalry usually revolves around accusing Australians of stealing national cultural icons like Phar Lap, Pavlova or Crowded House.

But I have to admit that when it comes to championing palaeontology (the study of fossils and what they can teach us about our biological heritage), the Australians have a good thing going.

Taking an idea that originated in America, many Australian states in recent decades have started adopting fossil emblems (alongside animal, floral, marine and mineral ones) that epitomise the natural history of each region.

In turn, these emblems can help promote fossil tourism, educational outreach and awareness of the need for fossil protection strategies.

Western Australia chose the 380 million-year-old Devonian fish Mcnamaraspis kaprios, while New South Wales picked a similarly aged fish, Mandageria fairfaxi. South Australia adopted the 550 million-year-old Spriggina floundersi from the dawn of complex life – the first animal in the fossil record whose left and right sides mirrored each other, like ours do today.

The Australian Capital Territory picked the 545 million-year-old brachiopod Atrypa duntroonensis, while a public vote in Victoria chose the 125 million-year-old giant amphibian Koolasuchus cleelandi. Queensland is currently holding a public vote to pick an emblem from 12 candidates that include dinosaurs, giant marine reptiles, an amphibian, a crocodile, a monotreme, a plant and a sea lily.

Aotearoa’s rich fossil record

Aotearoa New Zealand also has a rich fossil record that palaeontologists have used to unlock the evolution of our taonga (treasured) species and their unique whakapapa (lineage), in some cases stretching back tens to hundreds of millions of years.

In spite of this, there’s a distinct shortfall in palaeontological expertise and funding, which is affecting our ability to study and protect the local fossil record.

Read more: How did ancient moa survive the ice age – and what can they teach us about modern climate change?

Nonetheless, New Zealand’s fossils have captured the public imagination, such as the recently discovered 16-19 million-year-old giant Catriona’s shelduck (Miotadorna catrionae) from St Bathans. Fossils can also inspire future generations through interactive museum displays, outreach and volunteering on fossil digs.

Educational resources can be developed around our unique fossils to teach young New Zealanders how plants and animals evolved in response to the country’s dynamic geological and climatic history.

Fossil tourism

Emblems can also help teach us about the plight and importance of fossils. Newly exposed sites are not being excavated by experts, while other sites are eroding before our eyes. The potential information those sites hold is lost.

While fossil collection by amateurs provides some information, data retention is often substandard, and amateur collection can destroy small sensitive sites. Numerous moa bones, often illegally collected, still come up for sale despite the best efforts to stop this practice.

In a post-pandemic world, promoting sustainable tourism is more important than ever. Many regions are uniquely suited to fossil tourism, such as Waitomo and the West Coast. North Otago is already home to the Waitaki Whitestone Geopark, which promotes the geological and fossil history of the region.

Fossil tourism could also be developed at Foulden Maar, a 23 million-year-old lake deposit near Middlemarch in Central Otago, which the public fought to project from mining. It could house a museum and research facilities, and offer opportunities for people to collect fossils for themselves (as happens at Kronosaurus Korner in Queensland) or volunteer on digs (as they can at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs).

Time to choose

So, what should New Zealanders choose for their fossil emblem? Should we pick something flashy like the pouakai/Haast’s eagle (Aquila moorei) whose ancestor, the smallest eagle in the world, arrived in Aotearoa only about 2.5 million years ago and rapidly evolved into the world’s largest?

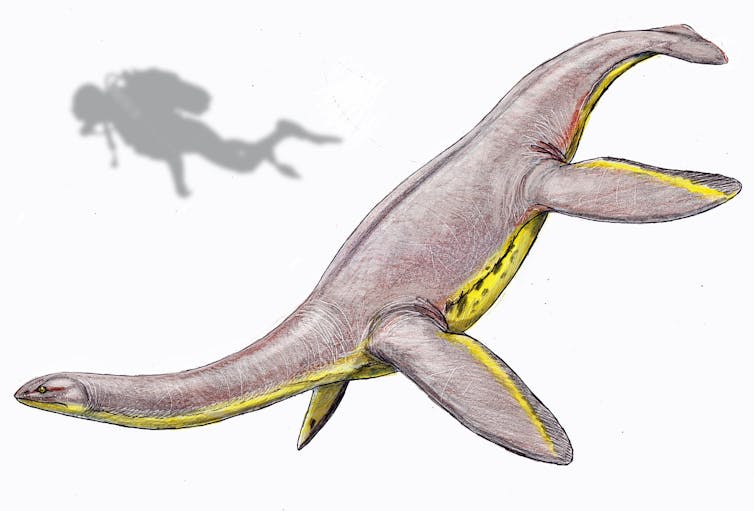

What about the 75 million-year-old plesiosaur Kaiwhekea katiki or the shark-toothed dolphin that capture my children’s attention?

We could agree that size does matter and choose the 55-60 million-year-old giant Bice penguin (Kumimanu biceae) or moa nunui/South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus). At the other end of the scale, how about the smallest fossils like 505 million-year-old trilobites, some of our oldest fossils?

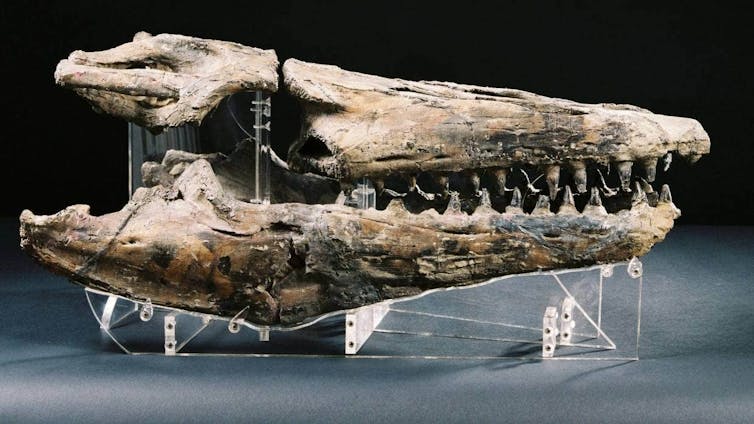

Should we consider historical value, like the first theropod dinosaur or one of the mosasaurs (such as Prognathodon overtoni) that pioneering fossil hunter Joan Wiffen discovered? Or should scientific value prevail, like the living pūpū whakarongotaua/flax snail (Placostylus ambagiosus), whose abundant fossil shells are teaching us a lot about the impacts of climate change and human settlement?

Read more: Proposal to mine fossil-rich site in New Zealand sparks campaign to protect it

I’m forming a committee of palaeontologists from across New Zealand to decide on a shortlist to put to a public vote. We would welcome input about what fossils to consider, whether we should have a single emblem representing New Zealand, or regional emblems, and even a yearly competition like the sometimes controversial Bird of the Year.

So get your iwi, whanau, school and local museum involved, lobby your local politicians and let us know what you think at nzfossilemblem@otago.ac.nz

Nic Rawlence receives funding from the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.