Adam Higginbotham was touring with his first book when got the idea from a frequent question.

The New York Times bestselling author of "Midnight in Chernobyl," Higginbotham had spent years researching the April 26, 1986 explosion, which caused the worst nuclear disaster in history.

"People often asked me whether I remembered where I was when I heard the news about Chernobyl," said Higginbotham in an interview with collectSPACE.com. "And I always had to admit I didn't, but what I did remember very clearly was where I was when I heard about Challenger, which happened almost exactly three months before."

"So when I started looking for something to write for my second book, Challenger was already on my mind," he said.

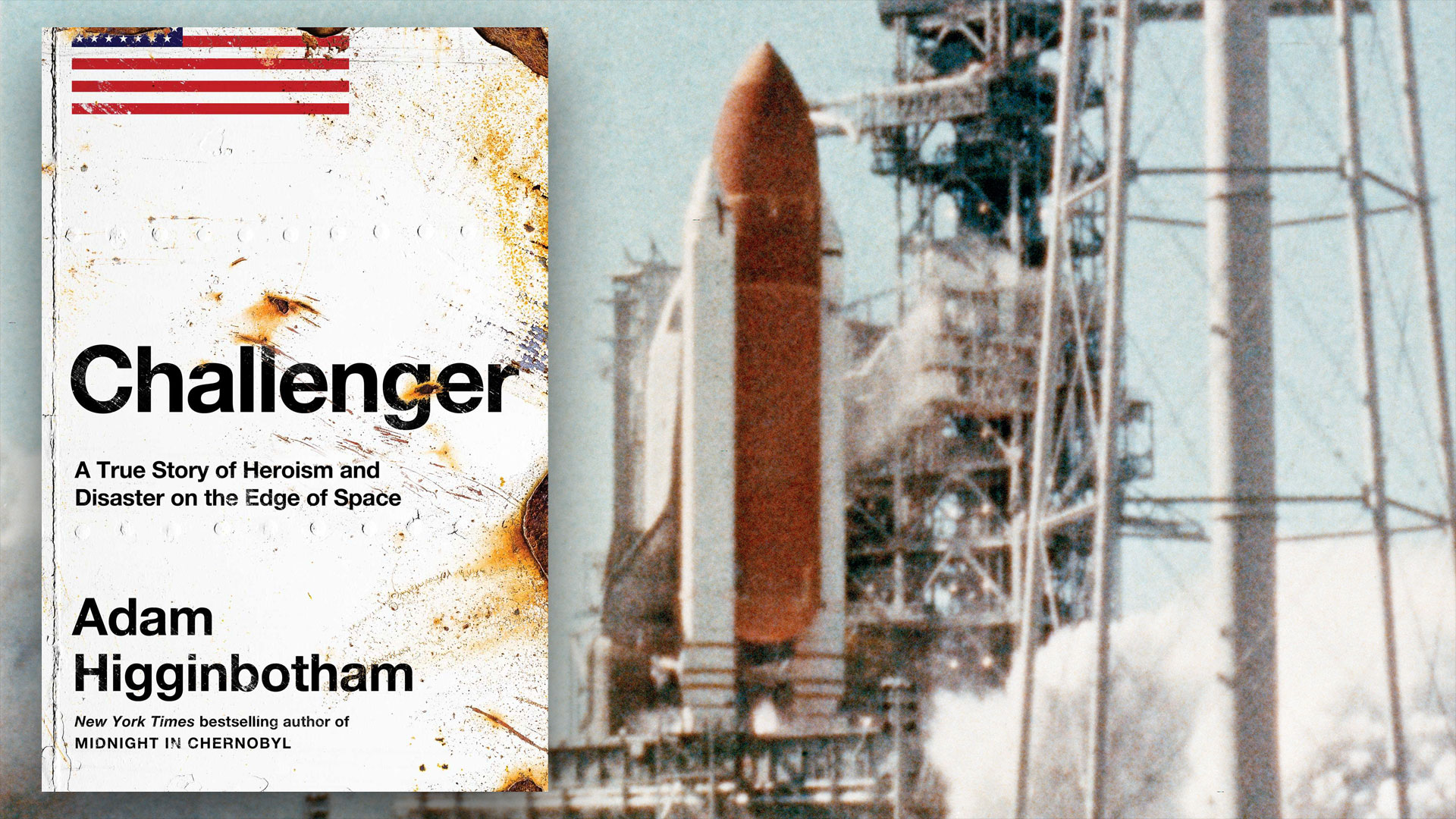

"Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of Space" hit store shelves on Tuesday (May 14).

Related: Space shuttle Challenger and the disaster that changed NASA forever

collectSPACE spoke with Higginbotham about "Challenger," how he went about researching the Jan. 28, 1986 tragedy and why he thinks the loss of the STS-51L crew resonated among so many to become not just a national, but international milestone event. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

collectSPACE (cS): Since you mention remembering, where were you when you first learned of the space shuttle Challenger disaster?

Adam Higginbotham: Because of the time difference — I was at school in England — I completed my school day and went out with my friends that evening. So I didn't learn about it until late that night, about probably nine or 10 o'clock, when I got home. My mother told me about it, and I just couldn't comprehend what she was telling me. I was so astonished by the news.

cS: Were you already interested spaceflight?

Higginbotham: I was fascinated by the space program when I was a kid. The shuttle program was really my part of the space program, because I was 12 when STS-1 was launched. I remember very excitedly watching it on TV in 1981.

I later reported off and on in magazine pieces about the space program, or about space travel, I should say, over the years.

cS: So you were inspired to write about the Challenger tragedy. There have been other books written on the topic. What did you think you could add to the subject that was not already covered?

Higginbotham: When I began to look at the available material and look at the sort of work that had been published about it up to that date, I realized that nobody had really attempted a serious narrative nonfiction account of everything that happened since immediately after the disaster, when the first couple of books were written in 1987 by journalists who had been there at the time.

Then I began to discover the amount of information that had come out in the years since then. Not only the number of people whose accounts might be more frank as the intervening years passed, but also I became aware of how many eyewitnesses were beginning to die. So there was an opportunity to tell this story before it disappeared into history and before those people who could talk about what they had seen themselves, and witnessed and experienced themselves, were no longer with us.

I also wanted to approach the story in a slightly different way, because I realized that the two accidents — the Challenger disaster and the Columbia accident in 2003 — had both overshadowed the public's conception of the shuttle program to the extent that people really were only aware of the disasters. That made, in retrospect, all of the achievements of the shuttle program seem to some extent to be in the shadow of failure.

So I wanted to write an account of of Challenger that told it in its full context. Not only the remarkable piece of engineering that the shuttle, itself, was — and it was far ahead of its time, a lot of its technology was — but also the kind of amazing achievements it made. There were front page news stories in the 1980s, in the years leading up to the Challenger accident, that people now, a whole generation of readers, might not be aware of.

And I also wanted to tell the stories of of the entire crew, because there were seven astronauts on board Challenger and yet so many accounts of what happened to them focused almost to the exclusion of everyone else on the story of ["teacher in space"] Christa McAuliffe.

cS: What was the reaction by the astronauts' family members when you approached them for interviews? Were they receptive of you writing a book now?

Higginbotham: They were extremely receptive.

I took my time before approaching them because I wanted to make sure that I fully understood the story and I understood their part and the way that they might feel about it before I approached them. I tried to make clear exactly the sort of book that I had in mind and what I wanted to tell. As I said, I wanted to put the story not only into its technological context, but also human context. And I think that when they understood what I had in mind, they were more receptive than they might otherwise have been.

Several of the family members had also read "Midnight in Chernobyl," and I think that went a long way to showing them the narrative that I had in mind.

Related: Remembering Challenger: NASA's 1st shuttle tragedy in photos

cS: You mentioned losing eyewitnesses to death. Beyond the astronauts' families, who were some of your primary sources for the book?

Higginbotham: Two of them died before the book came out. George Abbey [director of flight crew operations] recently died and Robert Frosch, who was the administrator of NASA who really did most to make the shuttle program come to fruition under President Carter's administration, were two of the first people who I spoke to. Bob Frosch died within within weeks of me talking to him.

cS: To the extent that you needed to assistance of people at NASA today, how supportive was the space agency?

Higginbotham: They could not have been more helpful. I was almost immediately put in touch with Brian Odom, NASA's chief historian, and one of the first things he said to me was that he had read "Midnight in Chernobyl" and thought that I was a good person to be writing this book. He liked the approach that I had taken with that book and really enjoyed reading it, so he said he would do anything he could to help me.

Brian was good to his word. He spent months organizing a research trip on my behalf where I was able to go to all of the principal locations at NASA facilities that were central to the story. And all of the public affairs officers I dealt with during that research trip were extremely helpful, and that really made the book possible.

cS: How so? Why was it important to visit those locations now, more than 35 years later?

Higginbotham: It made it possible to describe very precisely what the view from the roof of the Launch Control Center is like; what the light is like at 11:30 in the morning in January. It made it possible to describe what the view from the Johnson Space Center director's window is, what the meeting room on the ninth floor of Building 1 is like... it's all of those things.

It was those details in the book that wouldn't be possible to describe accurately without actually going into a lot of those places so that I could understand not only just topography, but the lighting and in some cases the smell, because that odor of old cigarette smoke and floor polish that lingered in the hallways of the astronaut office for more than 50 years is still there.

cS: "Challenger" has the potential of reaching a lot of different audiences, ranging from the space-interested public to those who know little about the subject and those who remember the tragedy versus those who were not yet born when it happened. Who did you write the book for?

Higginbotham: I write the sort of books that I enjoy reading. So it's a history book that is written with the pace and level of human detail of a novel. It is as factually accurate as it was possible to make, but it's written for a general reader principally.

I would hope that it has the level of technical accuracy that would satisfy someone who knows a great deal about the subject, but at the same time be sufficiently comprehensive to contain information that someone who has read books about the subject before and knows it well will still not necessarily be aware of. Partly because I've gathered information from a pretty wide variety of sources. I've conducted a lot of original interviews with eyewitnesses and people who worked on the program at the time. So through that I've gathered a lot of information and I have also unearthed quite a bit of archival material that those people may not be aware of and wouldn't have come across before.

One thing that I tried to make sure in both of my books is that they had the absolute minimum amount of technical detail necessary to understand the narrative and carry the story forward without their being too technical to get into the weeds. For me, that's the real difference between this type of book and a technical book that might be written purely for one specific part of the audience.

cS: On the subject of technical details, now that you've reviewed the tragedy and its causes in detail, do you agree with the findings of the Rogers Commission that investigated the loss of Challenger and its crew? Some other recent books have suggested that the commission's focus on NASA's management practices were not the root cause, but rather it was the budget constraints facing the program from its start and the design of what they argue was an inherently flawed vehicle.

Higginbotham: I don't think that those two things you just described are mutually exclusive. The Rogers Commission's report traces the limitations of the design of the shuttle back to its budget constraints. That's the original sin of the shuttle, and it was more than clearly laid out in the final findings of the commission.

I think that what is true is that the way in which the findings of the Rogers Commission were presented to the public by the media at the time were skewed in a very specific direction. I think their findings were extremely comprehensive, but they weren't necessarily reported that comprehensively at the time, or if they were, the way that people remember it was only the malfeasance on the part of a handful of senior NASA managers and obviously, the situation was more complex than that.

I hope I've shown all of these things in the book, because I was at pains to do so.

Related: NASA's fatal Challenger launch still echoes through the agency today

cS: Lastly, looking back, how did writing "Challenger" change your perspective of human spaceflight, if in fact it did?

Higginbotham: I'm not really sure it changed it at all.

One of the reasons why I wanted to write the book in the first place is because it's very difficult for people who weren't around in 1986 to understand exactly how shattering the Challenger disaster was, because nothing like that had ever happened before. It's hard for people to understand how shocking and, more specifically, how hard to believe, how hard to comprehend what was happening as it was happening.

And I think that it is really true to say that there was a world before the Challenger accident and the world after the Challenger accident, in the same way that there was a pre-9/11 world and post-9/11 world, because it was so unexpected. People had come to accept to a great extent that NASA was capable of almost anything and an accident like this simply wouldn't happen. For a few seconds after it happened right in front of them and for even longer than that, people found it almost impossible to conceive that it actually had been the shuttle that had been destroyed right in front of their eyes.

I think that once you've seen that happen and once you understand that that's possible, then the way you think of human spaceflight is different. And so seeing as I was 17 when it happened, I watched the footage on TV, and that's what changed my conception of human spaceflight. The things that have happened since, including the Columbia accident in 2003, have not significantly changed the way that I think about it. I understood that day exactly how dangerous and risky it was and how brave anyone who agrees to climb on top of a rocket must be, and I don't think working on this book really changed that.

"Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of Space" written by Adam Higginbotham and published by Simon & Schuster is available in book stores now.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2024 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.