On a gray morning in June, a group of students and teachers stood outside the Altgeld Branch of the Chicago Public Library clutching brightly colored maps.

They were there to learn from Cheryl Johnson, the executive director of People for Community Recovery, an environmental justice organization based out of the Altgeld Gardens public housing development on the city’s far South Side. The maps in their hands showcased the burden of pollution across Chicago’s neighborhoods.

The daughter of well-known environmental justice advocate Hazel Johnson, Cheryl Johnson told the huddle about her mother’s fight to protect Altgeld residents from environmental racism and pollution. Her message to the students was clear.

“What the government has done to our communities, and allowed this to happen, only you guys can change that. Only we can change that,” said Johnson.

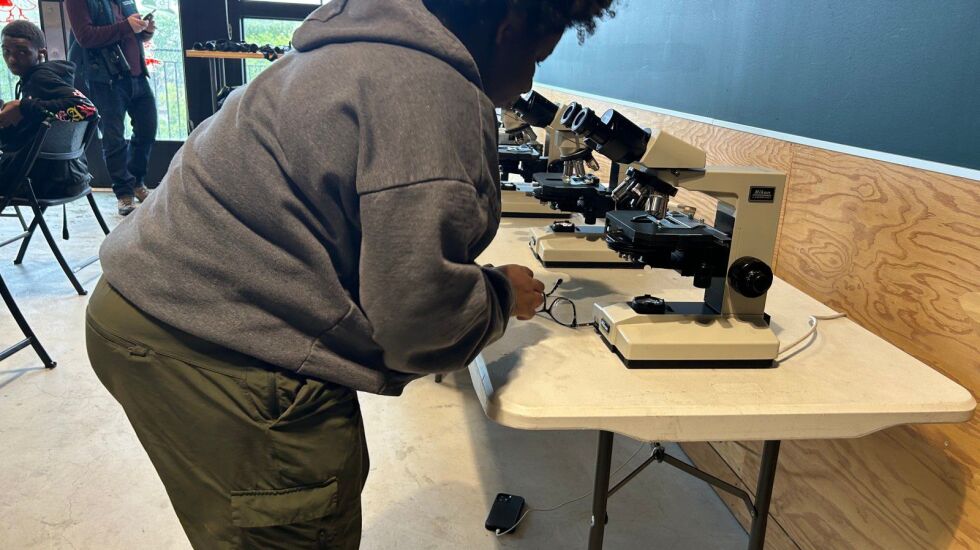

Altgeld Gardens was the first stop on a daylong tour – followed by visits to the Calumet Water Reclamation Plant and the Wild Mile, which is a floating island ecosystem on the North Branch of the Chicago River. The field day is part of a new, two-week long summer program called the Environmental Justice Freedom School, which is designed to provide Chicago Public Schools students with a hands-on environmental and climate justice education.

Chicago has a history of locating environmentally toxic sites in and near communities of color, a practice that federal investigations pointed to as recently as May.

Armed with their maps showcasing some key examples, educators say the course provides important tools to help students advocate for themselves and for their neighborhoods.

The program is sponsored and funded by the Chicago Teachers Union and the CTU Foundation – participating students and teachers receive a stipend. At the end of the two weeks, students and participating teachers shared culminating action plans that proposed a local climate solution for their own communities and schools.

Ayesha Qazi-Lampert, one of the organizers, said a big part of the program is building connections and engaging outside of the classroom.

“Through this experience, students are gaining those relationships and learning the complicated dynamics of being out in these spaces,” she said. “How do you advocate for these spaces, and protect these spaces and protect the communities they’re coming from?”

Learning about resources in their own backyards

Tyler Pruitt, a rising senior at Lindblom Math and Science Academy in West Englewood, said he wanted to learn “how to start the process of making a change, or rallying people to change something.” He said his interest in the environment started early, on a summer camp visit to a preserve.

“When I was out there, we stayed late and we saw stars. And I don’t really see stars like that,” Pruitt said, since light pollution from Chicago’s bright lights can blur the night sky. “They were talking about how a lot of the preserves are going away, and how I needed to protect it. Since then I’ve been wanting to protect [the area’s] forest preserves.”

This is the EJ Freedom School’s first year – but the inspiration for the program came from a long tradition of social justice training for students. Jackson Potter is another co-facilitator of the program and is vice president of the Chicago Teachers Union. He said the curriculum has a lot in common with a course he taught at the Chicago Freedom School, a youth organizing program. It centers “who’s impacted through a racial justice lens,” said Potter, and equips students to draw from their own personal stories to make change.

CTU has a climate justice project for educators — the Climate Justice Education Project. It shares resources and courses for teachers to bring accessible climate justice education into their classrooms. The EJ Freedom School is an extension of that concept, but focused on students. Qazi-Lampert said it provides a unique intergenerational space for those teachers and students to work together.

“These educators are designing what’s best for the schools, but also empowering and uplifting their student’s voices,” she said. “And then here, they get to work together… we’re having students and teachers from across the city learn from each other.”

Empowering students to take action

An important dimension to the EJ Freedom School is empowering students to take direct environmental action in their own schools – and much of this action centers around facilities. Issues like lead pipes and paint, peeling tile and old HVAC systems have surfaced in Chicago schools and have largely been under addressed. Their hope is that students can make their voices heard around these issues – especially in light of a 10-year facilities plan that is due from the district later this year.

In the first week of the program, students also spent a day learning about school buildings. They met with CPS facility managers, shared their concerns and asked questions about how the district plans to consider student voices around facilities. Students ended that day reading about lead exposure and practiced pitching their action plans to the Board of Education.

Tyler Pruitt, the Lindblom student, hopes to use what he’s learning to tackle the water system in his school. Pruitt said the school only has two or three water filters, and they don’t always work. Another student mentions his concerns around air pollution – how he often sees people driving trucks and cars by his campus, but nobody seems to be riding bikes.

As the bus pulled into CTU headquarters at the end of field day, students shared their excitement and curiosity about what they had learned. The conversation with Cheryl Johnson – focused on the decades-long struggle for justice undertaken by mother and daughter – resonated most with Angelo Baker, a student at Kenwood Academy.

“I’m really a firm believer in you can do anything you put your mind to, and they’re a testament to that,” Baker said. “With them never giving up on their dream, no matter how hard it got.”

Indira Khera is a metro reporter for WBEZ.