Producing hydrogen remains vital to Australia’s prosperity through the net-zero transition, according to a major strategy that lays a national pathway to becoming a global leader in the low-emissions technology.

The new National Hydrogen Strategy, released today by Federal Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen, aims to ensure Australia produces green hydrogen at a competitive cost. It’s also designed to guide investment and signal Australia’s bold ambitions to the world.

The document updates the first national hydrogen strategy, released in 2019 by then Chief Scientist Alan Finkel. I helped devise that strategy in my previous job as a federal public servant. I was also part of a panel convened to advise the government on the strategy released today (although it was up to the government whether the advice was accepted).

In my view, this new version of the hydrogen strategy improves on the old one, and responds to changing circumstances. But much remains unclear, including how the strategy interacts with existing policies, and whether taxpayer money will be used to fund hydrogen projects doomed to fail.

What is hydrogen?

Hydrogen is the smallest, lightest and most abundant element in the universe. It’s usually found as a gas, or bonded to other elements.

The element is used to make products such as fertilisers, explosives and plastics. In future, it may also be a zero-emissions replacement for fossil fuels in industries such as steel and chemicals manufacturing.

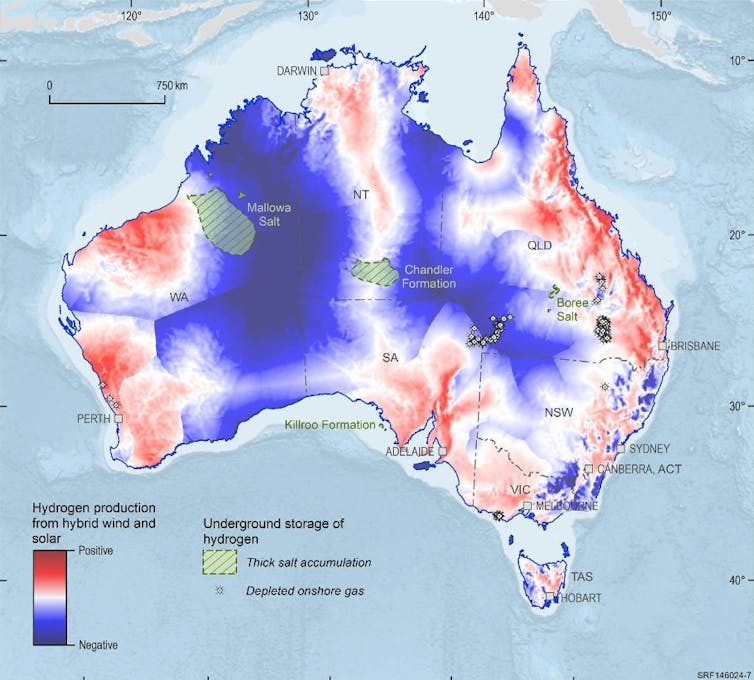

Hydrogen can also store electricity – so may one day be used to shore up domestic electricity supplies, or be transported in liquid form to countries less able to produce renewable energy.

Australia currently makes very low volumes of hydrogen using natural gas, which produces greenhouse gas emissions.

We are well-placed to produce “green” or zero-emissions hydrogen, through a process powered by renewable energy which releases hydrogen from water.

But creating a large green hydrogen industry won’t be easy. Today’s strategy – led by the federal government in collaboration with the states and territories – seeks to find a path through.

Aiming for a new target

The cost of producing green hydrogen is currently higher than what most buyers are willing to pay. The new strategy seeks to overcome this by scaling up production.

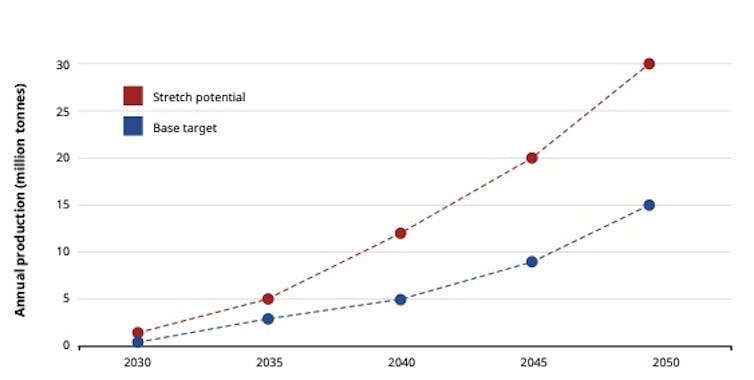

It sets production targets: 500,000 tonnes of green hydrogen a year by 2030, and 15 million tonnes a year by 2050.

The strategy also sets more ambitious “stretch targets” of 1.5 million tonnes by 2030 and 30 million tonnes by 2050. Achieving this will require finding new customers for the hydrogen we produce.

The new strategy dispenses with a previous target set by the Coalition government in 2020, to produce hydrogen for less than $2 a kilogram.

As I’ve written before, that target did not account for the high costs of moving and storing hydrogen, and switching to new technology that can use it.

Production and price targets can both be effective, if they are realistic. But whether those targets are achieved comes down to governments’ policy choices.

Time to prioritise

The strategy identifies three industries – iron, alumina and ammonia – where hydrogen could best be used to build new export industries. It also identifies three areas where hydrogen shows promise in cutting emissions: aviation and shipping, electricity storage and freight trucks.

These priorities show governments are coming to grips with hydrogen’s limitations, in a technical and economic sense. For example, in passenger vehicles, hydrogen has lost out to electric cars. And using hydrogen to replace natural gas in homes is far more expensive than simply going electric.

What’s not clear is how the new priorities will guide government decisions. For example, will priority sectors get first dibs on funding or infrastructure assistance? And will governments stop funding hydrogen projects once it becomes clear they are not competitive?

Without guidance on these and other questions, investors may find it hard to decide where to put their money.

A nuanced view of exports

The 2019 strategy was squarely focused on exporting liquid hydrogen to prospective buyers in Japan and South Korea.

Now, the likely big buyers are in Europe. In fact, Bowen today announced Australia and Germany are working towards a A$660 million deal, funded equally by the two nations, to guarantee European buyers for Australia’s green hydrogen.

Importantly, however, hydrogen is very difficult and expensive to transport. As my colleagues and I have written, Australia should instead focus on using hydrogen to produce green iron from iron ore.

The new strategy treads a fine line on the question of exports. It identifies priority sectors and aims to develop those new industries in Australia. But it doesn’t rule out liquid hydrogen exports.

Getting communities on board

The 2019 strategy emphasised the need for community acceptance of hydrogen technologies – particularly in relation to safety. Overseas experience showed communities feared the risk of explosions and fires from this volatile gas.

Safety remains a meaningful concern in the strategy. But the new version also emphasises community benefits, such as jobs and more diverse regional economies.

In particular, the document seeks to ensure proper consultation with First Nations people and to manage impacts on water.

Cart before the horse?

This strategy interacts with two measures the Albanese government announced in recent months: the $2 billion Hydrogen Headstart grants program, and a tax credit for hydrogen producers.

The credits are only available for ten years, and there’s nothing in their design to ensure they help the priority sectors. It would be a shame if they were taken up by producers pursuing hydrogen technology that will never work.

More broadly, it’s not clear whether these measures were calibrated to achieve the strategy’s production and export targets. It’s also unclear whether governments would pull the plug on support for technologies that turn out to be less promising than first thought.

Where to next

The hydrogen strategy will be reviewed again in 2029. Its success can be measured by watching for the following developments:

large hydrogen projects attracting finance and starting construction

hydrogen suppliers signing multi-year contracts with users, possibly including exports

the building of hydrogen storage facilities, and wind and solar farms to supply electricity for hydrogen production

commitments and timelines from domestic heavy industry to replace fossil fuels with hydrogen.

If these signs don’t emerge in the next decade, Australia may need to adjust its hydrogen strategy, and global ambitions, accordingly.

Alison Reeve does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article. She led the development of the first National Hydrogen Strategy in 2019, and was a member of the stakeholder advisory group for revised 2024 National Hydrogen Strategy. Since 2008, Grattan Institute has been supported in its work by government, corporations, and philanthropic gifts. A full list of supporters is published at www.grattan.edu.au.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.