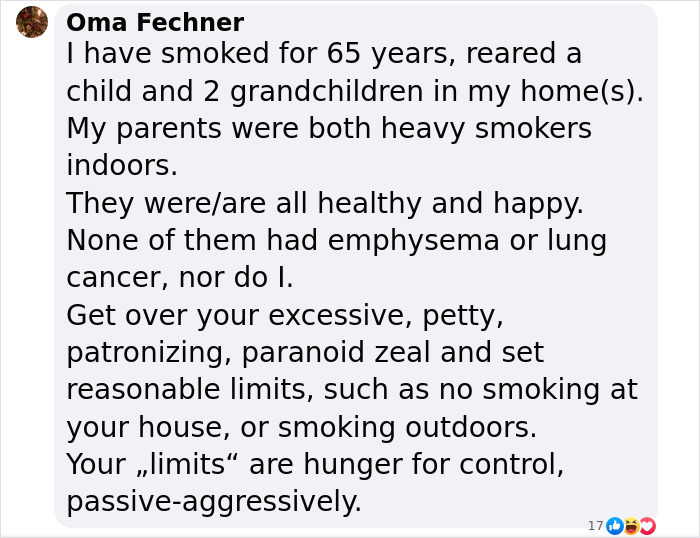

Slate magazine has an advice column and podcast called “Care and Feeding,” which addresses readers’ questions about kids, parents, and family life.

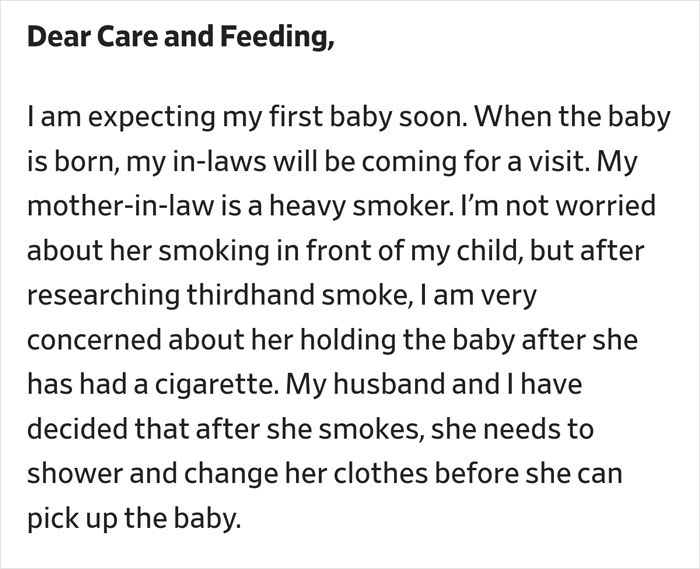

One time, they received a letter from a woman expecting her first baby. She shared her excitement about the upcoming arrival but expressed concern about navigating a delicate situation with her mother-in-law.

After learning about the dangers of third-hand smoke, she and her husband wanted to protect their baby but were worried about how to communicate these boundaries without causing hurt feelings.

Smoking is more than a personal habit—it can affect the people around you

Image credits: Yaroslav Shuraev / Pexels (not the actual photo)

So this woman asked an advice column about setting boundaries for her baby’s safety

Image credits: SLATE

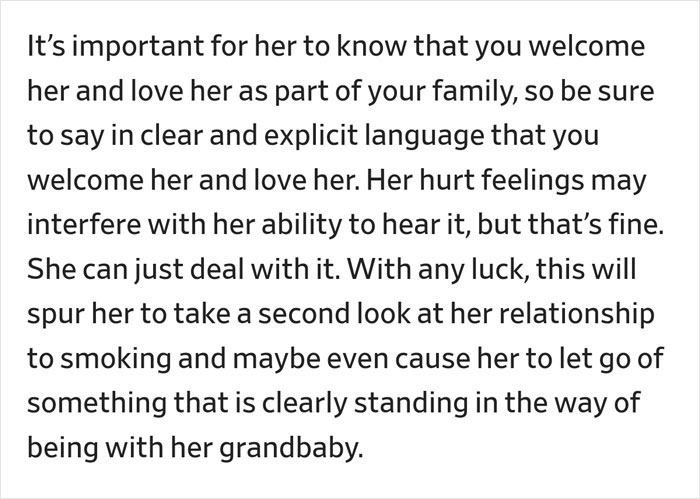

The reply she received validated her concerns, but also gave practical advice

Image credits: Sarah Chai / Pexels (not the actual photo)

There’s some truth to the mom’s worries

According to Jon O. Ebbert, M.D., whose research at Mayo Clinic focuses on disease prevention, early cancer detection and digital health care, thirdhand smoke is made up of the pollutants that settle as tobacco is smoked.

“The chemicals in thirdhand smoke include nicotine as well as cancer-causing substances such as formaldehyde, naphthalene and others,” he said.

“Thirdhand smoke builds up on surfaces over time. It can become embedded in most soft surfaces such as clothing, furniture, drapes, bedding, and carpets. It also settles as dust-like particles on hard surfaces like walls, floors, and in vehicles. Thirdhand smoke can remain for many months, even after smoking has stopped.

Ebbert highlighted that thirdhand smoke poses a potential health hazard to nonsmokers — especially children. “Substances in thirdhand smoke are known to be hazardous to health. People are exposed to the chemicals in thirdhand smoke when they touch contaminated surfaces or breathe in the gases that thirdhand smoke may release,” he added.

Part of the reason why infants and young children are at greater risk for exposure to thirdhand smoke than adults is because how they interact with the environment: the littles are eager to crawl around and put the things that are around them in their mouths.

Furthermore, Ebbert said thirdhand smoke cannot be eliminated by airing out rooms, opening windows, using fans or air conditioners, or confining smoking to only certain areas of a home. Traditional household cleaning usually cannot effectively remove it.

Jasmine Reese, M.D., an adolescent medicine specialist and the director of the Adolescent and Young Adult Specialty Clinic at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, said there is no safe amount of firsthand, secondhand, or thirdhand smoke to breathe in.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that we prevent exposure of any tobacco smoke to all children,” she noted. “Preventing exposure means not allowing anyone to smoke in your home or your car. Also, ask caretakers such as family members or babysitters to be mindful and respectful of your rules of not smoking or vaping around your children. Oftentimes, people feel that smoking is safe if they change their clothing or smoke outside. The best and only way to completely prevent inhaling thirdhand smoke is to quit or to not start smoking at all.”

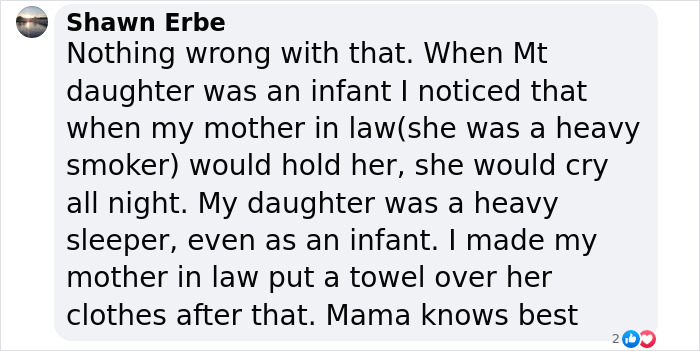

Some people believe the mom’s concerns are legitimate

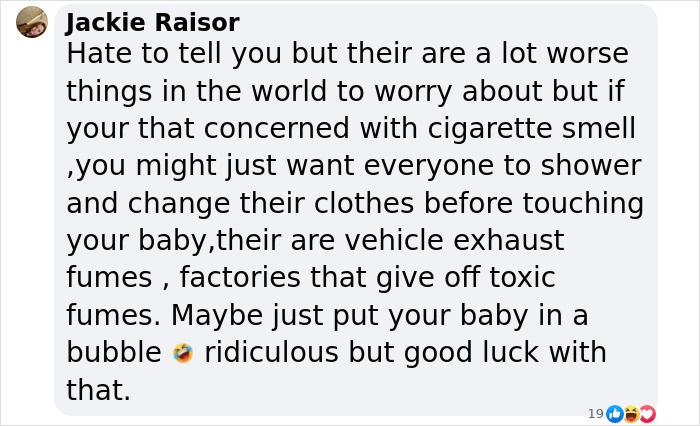

But others think she’s reaching too far