WHO hasn't heard of the once popular wartime musical South Pacific? Well, probably most of today's generation, and I can't blame them.

The colourful 1958 American romantic film was derived from the Rodgers and Hammerstein stage play, which in turn came from the pen of author James A. Michener's 1947 short-story collection Tales of the South Pacific.

His Pulitzer Prize-winning first book was loosely based on yarns he'd gathered during his war service in the South Pacific in World War II. Key figures included the irrepressible scrounger Luther Billis, Bloody Mary and the French planter turned reluctant coastwatcher, Emile de Becque.

But the musical was highly sanitised, as the raw truth was unpalatable in the 1950s to audiences who were, by then, sick of war and horror.

And one of Michener's true-life tales also never made it to the screen. This yarn involved the futile rescue attempt of a lost coastwatcher who was feared to have been caught, suffering a grim, lonely death.

However, a little earlier, the musical did give a big break to former coffin polisher turned bodybuilder Sean Connery in Glasgow, Scotland. He had a small role in the adapted musical before becoming the original cinematic James Bond.

But it wasn't until 1960 that Hollywood revisited the dramatic potential of real-life WWII coastwatchers in the comedy-drama The Wackiest Ship In The Army, starring Jack Lemmon. At least the film acknowledged the real danger and drama faced by Aussie coastwatchers, who were dropped on remote Pacific islands to spy from jungle hilltops on the well-entrenched Japanese enemy. The film also had an Aussie actor, screen icon Chips Rafferty, in a supporting role. But, since then, Hollywood hasn't come knocking. That's probably because few Americans were actual coastwatchers in the war.

But what a staggering untapped story source there is in the life histories of these incredibly brave and resourceful men who, although hidden, became and eyes and ears of the Pacific. They were, in fact, the early warning system for the Allies, reporting every move of the Japanese invaders back to Aussie military intelligence in Townsville.

These "special reporting officers" comprised everyone from settlers, to patrol officers, to harbour masters, local police, postmen, European planters and missionaries.

The Pacific network of coastwatchers stretched over half a million miles of ocean. They reported hundreds of aircraft sightings, identified ships of secret enemy convoys, and relayed information on Japanese troop movements. They announced otherwise unobtainable weather information, spirited away hundreds of civilians and soldiers, and knew their enemy's moves in advance.

Established by the Royal Australian Navy after WWI, the coastwatchers by 1928 were a loose organisation until WWII began in the Pacific in 1942.

Their commander, Eric Feldt, always saw his network as passive observers rather than an active military force, or even a guerrilla army. Over time, however, his network evolved into a native-augmented guerrilla force under the direction of Australian commandoes of the special forces.

Facing the Japanese directly in battle, they were eventually credited with killing almost 5500 enemy soldiers with 74 captured.

The price paid by the "watchers", however, was high. About 56 European and 20 natives died in action, in often barbaric circumstances at the hands of the enemy, often by beheading.

One of the most amazing survival stories of these people hidden in the jungle concerned a former native policeman, Jacob Vouza. The faithful scout was caught by Japanese soldiers and tied to a tree where his face was repeatedly slammed by rifle butts.

Seven separate times he was then stabbed with bayonets and had his throat slashed by an officer's sword. The bleeding Vouza pretended to be dead and later wriggled out of his ropes before crawling and stumbling into the dark jungle to escape.

After the story of Vouza's ordeal reached the ranks of the US marines, the coastwatchers gained a somewhat mythical status.

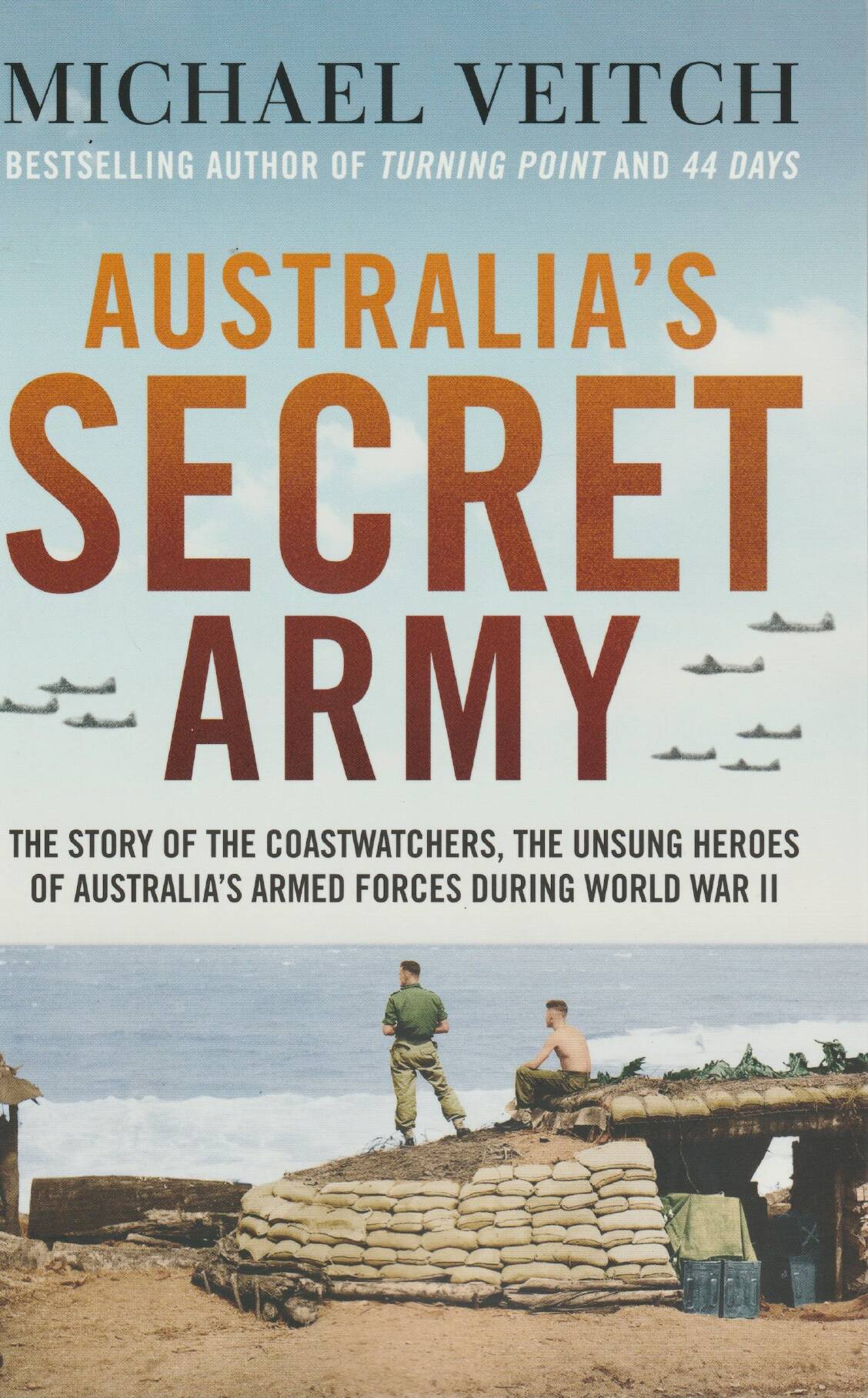

The latest book to immortalise the coastwatchers, and the hidden role of their native friends, is Australia's Secret Army by Michael Veitch. And he does a superb job.

I had initial misgivings about the 340-page book, because the blurb describes the men as "unsung heroes" of Australia's army forces during World War II on the nation's northern border from New Guinea to the Solomon Islands and elsewhere. Maybe by now, the crucial role of the coastwatchers in WWII has been overlooked, but there have been at least 10 books on the subject. These are probably mostly out of print, so Veitch's book is a very timely reminder of the coastwatchers' invaluable contribution.

Other issues I had were the lack of photographs, only one map being included, and being slow to start. But minor quibbles aside, Veitch's book is a lively, entertaining and informative read. Some stories just never get old.

One of the most remarkable episodes of the WWII coastwatchers was their success in managing to haul around cumbersome communication dinosaurs - the AWA Teleradio 3B transmitter/receivers. These were gargantuan, with two of its wet cell batteries each being as large as car batteries. Coastwatchers seeking to relocate positions to avoid capture also needed between 12 to 16 native bearers to transport this equipment. The charging engine was also noisy, often having to be partially buried in pits to muffle the sound.

The most well-known Aussie coastwatcher was 'Reg' Evans, who alerted rescuers to future US president John F. Kennedy, who was in the Solomons after his patrol torpedo boat (or PT 109) was cut in half by a Japanese destroyer one night in August 1943.

Surprisingly, Veitch reveals that the daring PT-boat crews were not highly respected by the US naval establishment who labelled them "the hooligan navy" and limited the promotion paths of its maverick officers. A common joke among veterans was that the author of the famous PT book They Were Expendable ought to have penned a sequel entitled They Were Useless.

The final word on the role of the Aussie coastwatchers should go to the US Navy commander of the South Pacific, Admiral Bull Halsey, who said: "The coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal and Guadalcanal saved the Pacific."

Australia's Secret Army by Michael Veitch - published by Hachette Australia, $32.99.

WHAT DO YOU THINK? We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on the Newcastle Herald website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. Sign up for a subscription here.