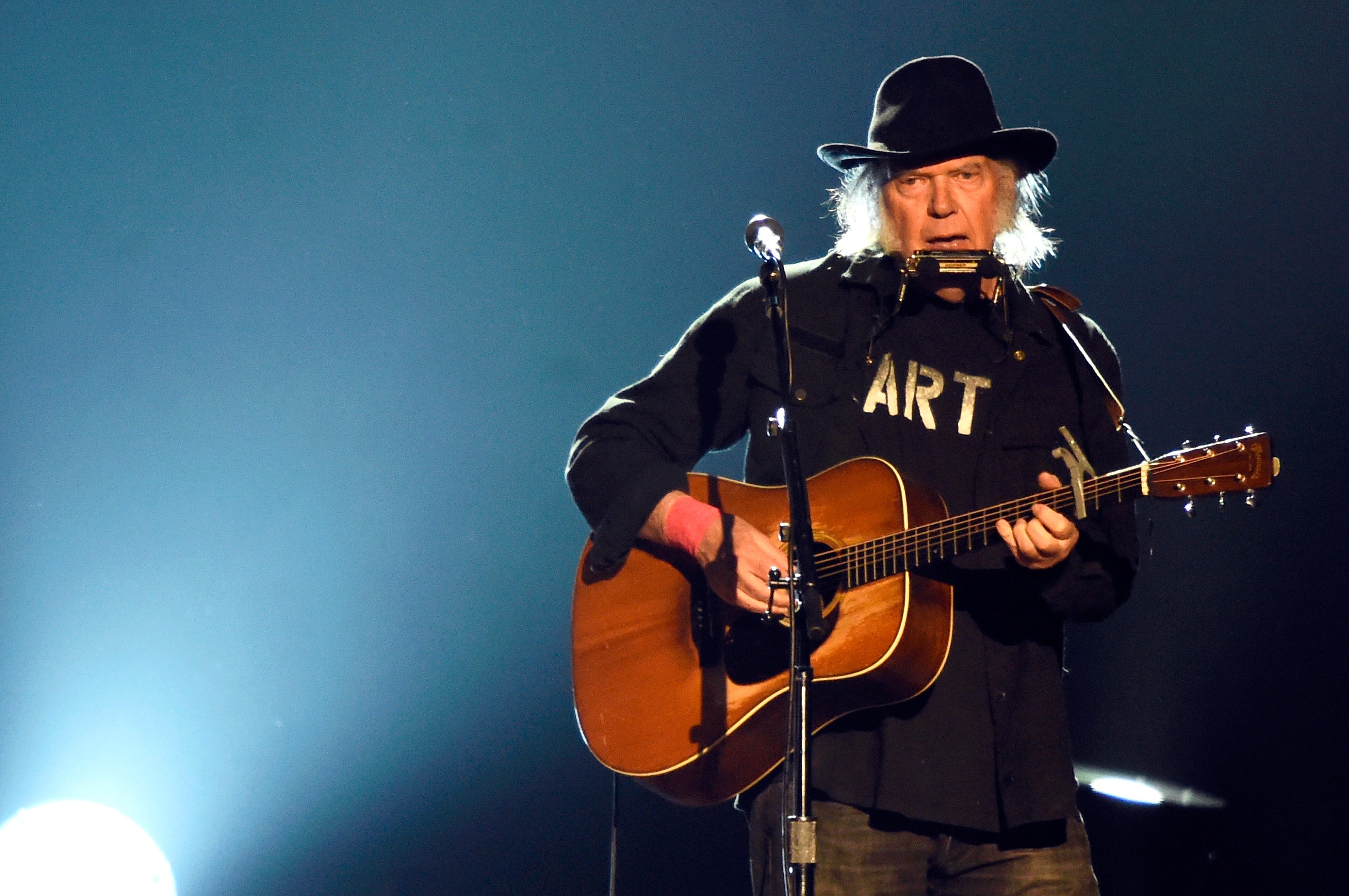

Days before Donald Trump began his second reign of error, a new track surfaced that captured the spirit of this ominous moment in history, its chorus warning: “Big change is coming/ Coming right home to you.” This urgent salvo isn’t the work of some young punk firebrand or righteous rap soothsayer, but of a man with over six decades in the game. For that is Neil Young there, stomping with purpose through the snow in the music video, his bulky figure, wild eyes and ice-white lambchops making him resemble a haphazardly shaven bear. “Could be bad and it could be great,” he adds, of that titular “Big Change” – though given the song’s visions of “big drums drumming/ heading up the wrong parade”, the news doesn’t sound promising.

Cometh the hour, cometh the Crazy Horseman. Neil Young has traced his own wayward, ragged and glorious path for more than 60 years. Disdainful of fame and, sometimes, of his dearest friends and bandmates, in blind allegiance to his beliefs in that moment (and that moment alone), he has split successful groups at their peak and jack-knifed in unexpected creative directions (and been sued for it). He withdrew his music from Spotify for two years to protest Joe Rogan “spreading fake information about vaccines”, and – on his aptly named webpage, the Times-Contrarian – briefly announced he was boycotting this year’s Glastonbury, which he is scheduled to headline, because the BBC’s involvement made the festival “a corporate turn-off”.

Somewhat baffling, that last one. But it confirms the mulish nature that has won him the admiration of generations of kindred iconoclasts, from Devo to Nirvana and Pearl Jam, for whom his integrity and relevance are inextinguishable. Indeed, so unpredictable is Young that “Big Change” could easily be heard as a Maga anthem, and certainly the visuals of a grizzled Young, flag in hand, stomping away, echo those of the rioters of Jan 6. After all, in the Eighties Young seemed to flirt for a time with support for Reagan, and his politics don’t easily align with any one side; he could perhaps be described as “chaotic liberal”, though his devotion to ecological issues, his intolerance of racism and the threats to sue Trump for using “Rockin’ in the Free World” at his rallies quickly scorch such a theory. But there’s an ambiguity there that is 100 per cent Neil.

Young comes from headstrong stock, his father a newspaperman, his mother a direct descendant of a fighter in the American Revolution. A Canadian native, in 1965 he joined The Mynah Birds, a Toronto garage band fronted by future superfreak Rick James. The band won a contract with Motown only to implode after James – then awol from the US navy – was picked up by the cops. Young purchased a hearse, relocated to Los Angeles and, in April 1966, while stuck in the hearse in traffic on the Sunset Strip, drew the attention of an old acquaintance from Canada, singer-guitarist Stephen Stills. Reaffirming their friendship that night, the duo promptly formed Buffalo Springfield. But the group would prove a combustible ride. Young quit after their first album, over a “belittling” booking on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show; The Byrds’ David Crosby stood in (and for a subsequent performance at 1967’s legendary Monterey Pop Festival). Young rejoined for that year’s Buffalo Springfield Again, before the band imploded once more, this time for good.

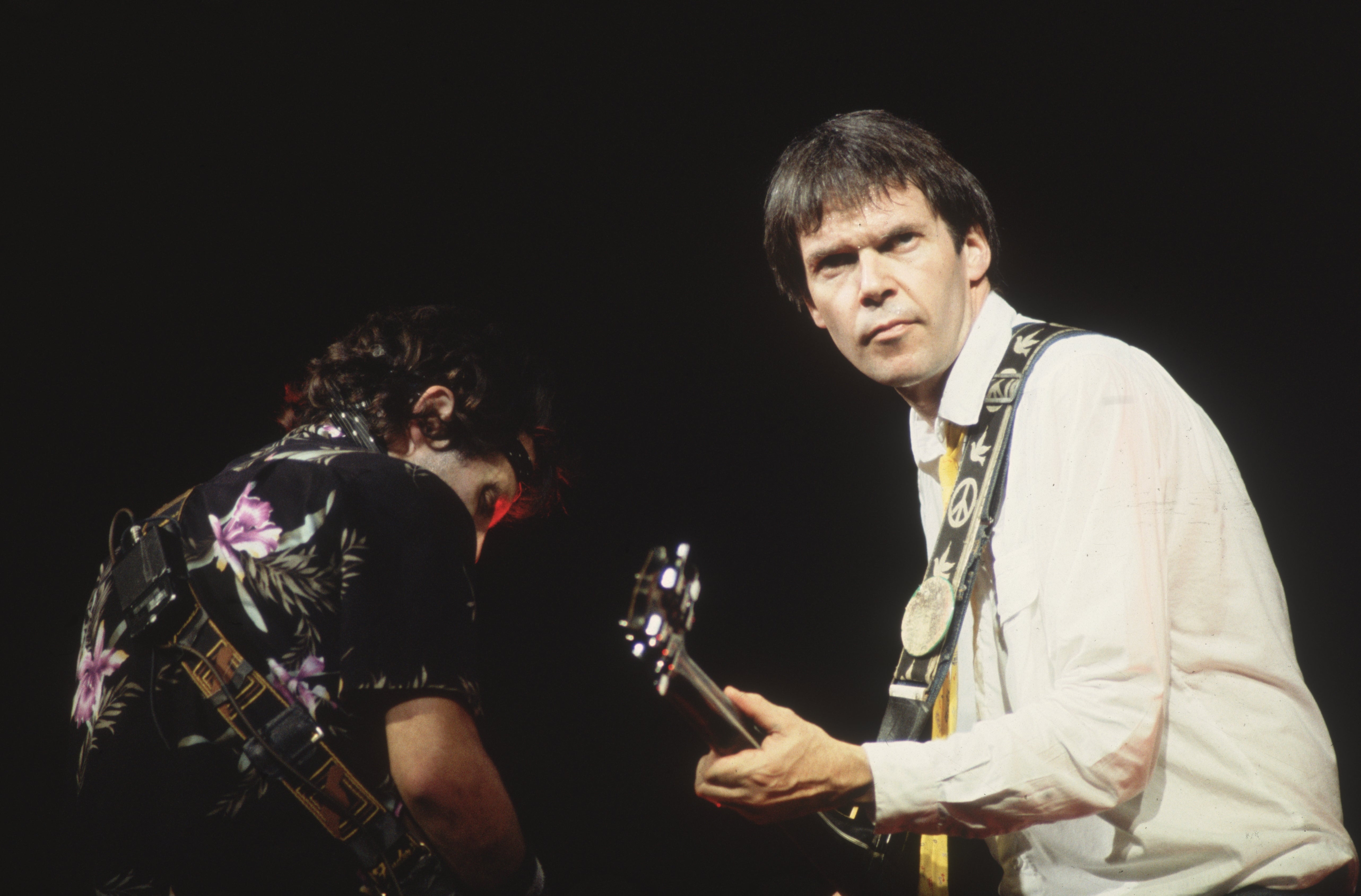

He wasn’t on the skids for long. By the dawn of the next decade, Young was rock royalty, having joined old sparring partner Stills, Crosby, and Brit Graham Nash, from post-Merseybeat group The Hollies, in their supergroup. Young lent their chart-pleasing harmonies a razor edge. He remained a maverick among the hippy enclave, obstinately refusing to be filmed during the band’s legendary Woodstock performance. His 1970 solo masterpiece, After the Gold Rush, and chart-topping 1972 follow-up Harvest made Young a solo star, his gauzy country-folk placing him at the vanguard of a wave of singer-songwriters.

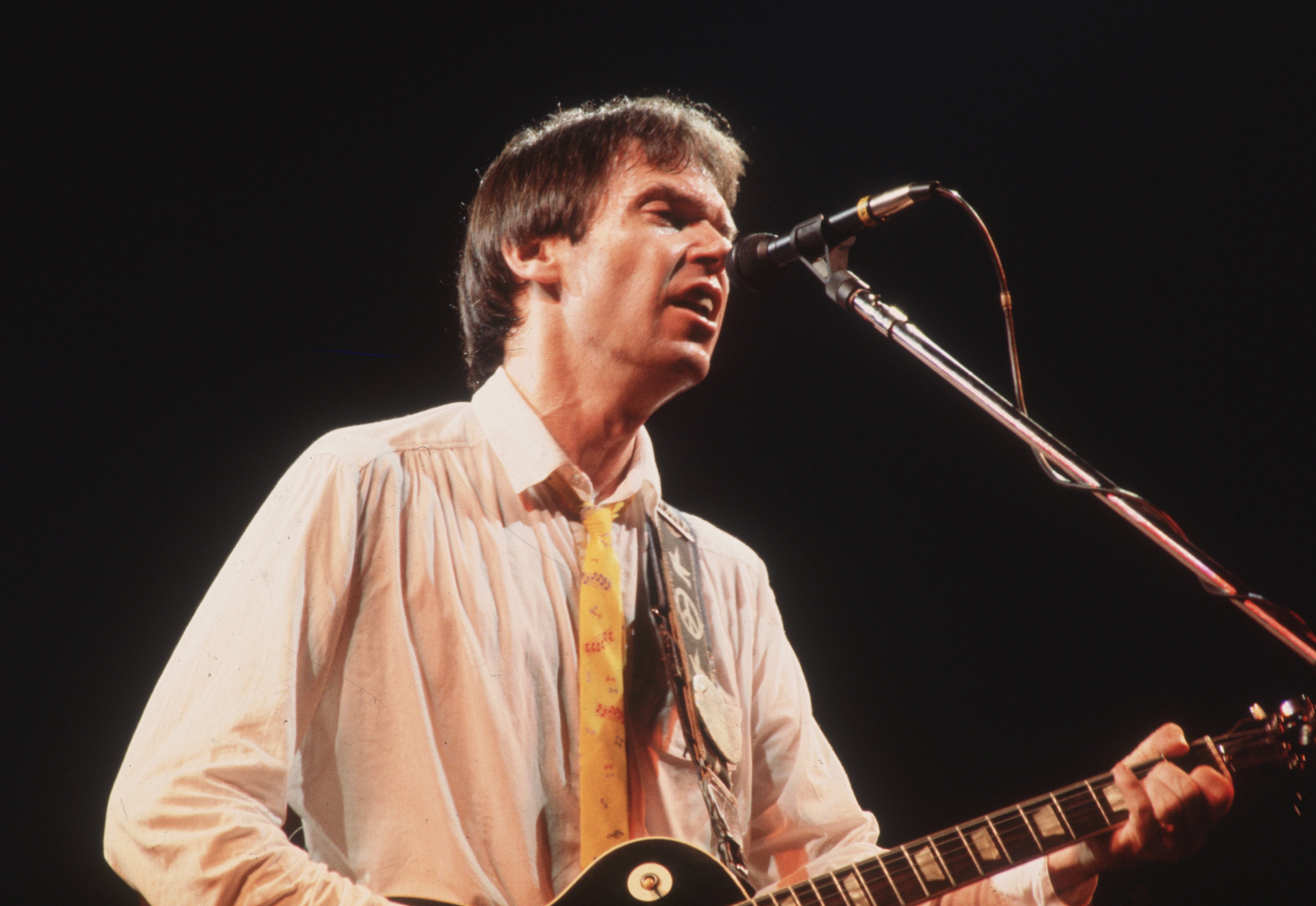

He could easily have coasted in this lane for years to come, delivering acoustic panacea to soothe those former hippies who spent the “Me Decade” – as writer Tom Wolfe dubbed the 1970s – surreptitiously devolving into yuppies. But Neil’s a weirdo, and an artist for whom music is more catharsis than career. The drug-related deaths of two close friends, Danny Whitten (guitarist with his regular backing band, Crazy Horse) and roadie Bruce Berry, sent Young into an emotional tailspin that yielded a sequence of challenging, grief-maddened, often fiercely anti-commercial albums navigating this loss. The key chapter in this so-called “ditch trilogy”, Tonight’s the Night, was recorded in 1973, but cold feet saw Young shelve it until 1975. However, this didn’t stop him performing the then unreleased album in full to baffled fans in 1973, promising throughout to play a song they already knew – and doing so by reprising the unheard record’s opening title track as set-closer. He never said he was a crowd-pleaser.

On the Beach, released in 1974, was a bummer that alienated his closest friends; Crosby in particular objected to the scourging “Revolution Blues”, which imagined its way into the mind of a Manson-esque murderer who hates Laurel Canyon stars “worse than lepers” and fantasises how he’ll “kill ’em in their cars” – Manson, after all, had shattered Canyon dwellers’ sense of security, so Young’s bleak tune would have fed into Crosby’s native paranoia. Young’s relationship with his CSNY bandmates was often fractious – he quit following a lucrative but cocaine-blighted 1974 tour, reconvened for an album with Stills, 1976’s Long May You Run, then quit that concert tour halfway via telegram, telling Stills: “Funny how some things that start spontaneously end that way. Eat a peach. Neil.”

Young was Seventies rock’s unstable element. He didn’t see himself as part of the entitled Hollywood rock set, whatever his wealth and habits. And when punk-rock arrived, unlike his contemporaries Young welcomed the movement as a corrective, not an irritant or threat. His 1979 album Rust Never Sleeps ended on a new anthem, “Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black)”, that namechecked Sex Pistol Johnny Rotten. The song had grown from a 1977 collaboration with punk-minded Ohio art-rockers Devo, and found Young ruminating on rock’n’roll’s youth-orientated built-in obsolescence, deciding “It’s better to burn out than to fade away”.

Young seemed committed to both destinies throughout the 1980s. He signed a new deal with Geffen Records, then lit off on a quixotic, baffling tear of records that often sounded little like Neil Young, including 1982’s Trans, an electronic rock record that saw Young sing through a vocoder, and 1983’s rockabilly set, Everybody’s Rockin’. Geffen ended up suing Young for making music “unrepresentative” of himself. This adversarial relationship with his corporate paymasters only further endeared Young to the nascent alternative-rock generation. In 1991, New York art-punks Sonic Youth opened for Young’s “Smell The Horse” tour, and while Young’s spoilsport crew spent the tour dialling down Sonic Youth’s caterwauling amplifiers, he was impressed by the band’s embrace of noise. Subsequently, he released Arc, a 35-minute, single-track symphony of noise compiling passages of inchoate feedback from the tour – proof this ornery veteran was listening to what was going on at that moment.

And the moment was listening to him. Later that year, the unexpected success of Nirvana’s Nevermind signalled an uprising of these underground groups, many so indebted to Neil’s sound and spirit that he was christened “the godfather of grunge”. Young’s latest album with Crazy Horse, Ragged Glory, was a loud, distorted guitar-rock record not a million miles from what Generation X was eating up. But this kinship would take on a dark resonance in 1994, after Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain quoted “Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black)” in his suicide note.

In his acceptance speech at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame the following January, Young thanked Cobain “for all of the inspiration”. Later, he spoke of recognising a kindred spirit in the late singer: “I could really hear his music,” he told Spin. “There’s not many absolutely real performers.” Young had tried to reach out to Cobain the week he died. “I might have been able to make things a little lighter for him, that’s all,” he said. “Just lighten it up a little bit.”

From experience, Young knew the only way through the grief was diving into the ditch. Released the summer after Cobain’s death, Sleeps with Angels was a brooding, troubled, brilliant record, its title track obliquely referencing the tragedy, its chorus howling “Too late! Too soon!” Further cementing his connections to grunge, Young recorded a whole album, 1995’s Mirrorball, with Seattle’s other main contender, Pearl Jam, and played guitar – brilliantly – on the group’s Merkin Ball EP, embarking on several world tours with them. It was a dream come true for these unabashed Neil stans. “He changed our band,” singer Eddie Vedder told me in 2009. “He taught us about dignity. When we first met he said, ‘Man, I envy you guys. You don't have any “baggage”.’ He meant that we’d only recorded one album. But all I wanted at the time was that ‘baggage’.”

In 2016, newsman Dan Rather questioned Young on the burn out/fade away dichotomy. “Hendrix, Cobain, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens all went at their peak, and that’s the way everybody remembers them,” Young replied. “And that’s what rock’n’roll’s all about: that edge, the peak, the thing. In rock’n’roll, exploding is not bad.” But Young did not explode, has not burned out nor faded away. He’s found a third way: raging until the dying of the light, integrity, relevance and ornery-ness intact.

Connecting to youthful kindred spirits like Cobain and Vedder revivified Young’s maverick energy. And in the years that followed, while his Boomer contemporaries have gone soft and fallen off, he’s remained engaged, recording concept albums about environmentalism (Greendale) and against the Iraq conflict (Living with War), reuniting Buffalo Springfield and starting a new group, Promise of the Real, with musicians over 40 years his junior, and firing the very first salvo against this dark new era in America. Every wilful new turn in his career is a reminder of Young’s stubborn, fearless, life-affirming spirit, something too precious to hold to some dumb live-fast-die-young precept. As he told Rather almost a decade ago, impish glimmer visible in his eye, rock’n’roll might want its stars to explode, but “there’s a lot more to life than rock’n’roll”. Long may he run.