A 6-year-old Neanderthal child had Down syndrome, a new analysis of an oddly shaped ear bone found in a cave in Spain suggests.

The finding is the first known case of Down syndrome in Neanderthals, our closest human relatives that lived in Eurasia from about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago. The fact that the child, nicknamed Tina, lived into early childhood suggests that her Neanderthal group cared for her, providing evidence that Neanderthals engaged in altruistic behavior.

"This child would have required care for at least 6 years, likely necessitating other group members to assist the mother in childcare," the researchers wrote in a new study, published Wednesday (June 26) in the journal Science Advances.

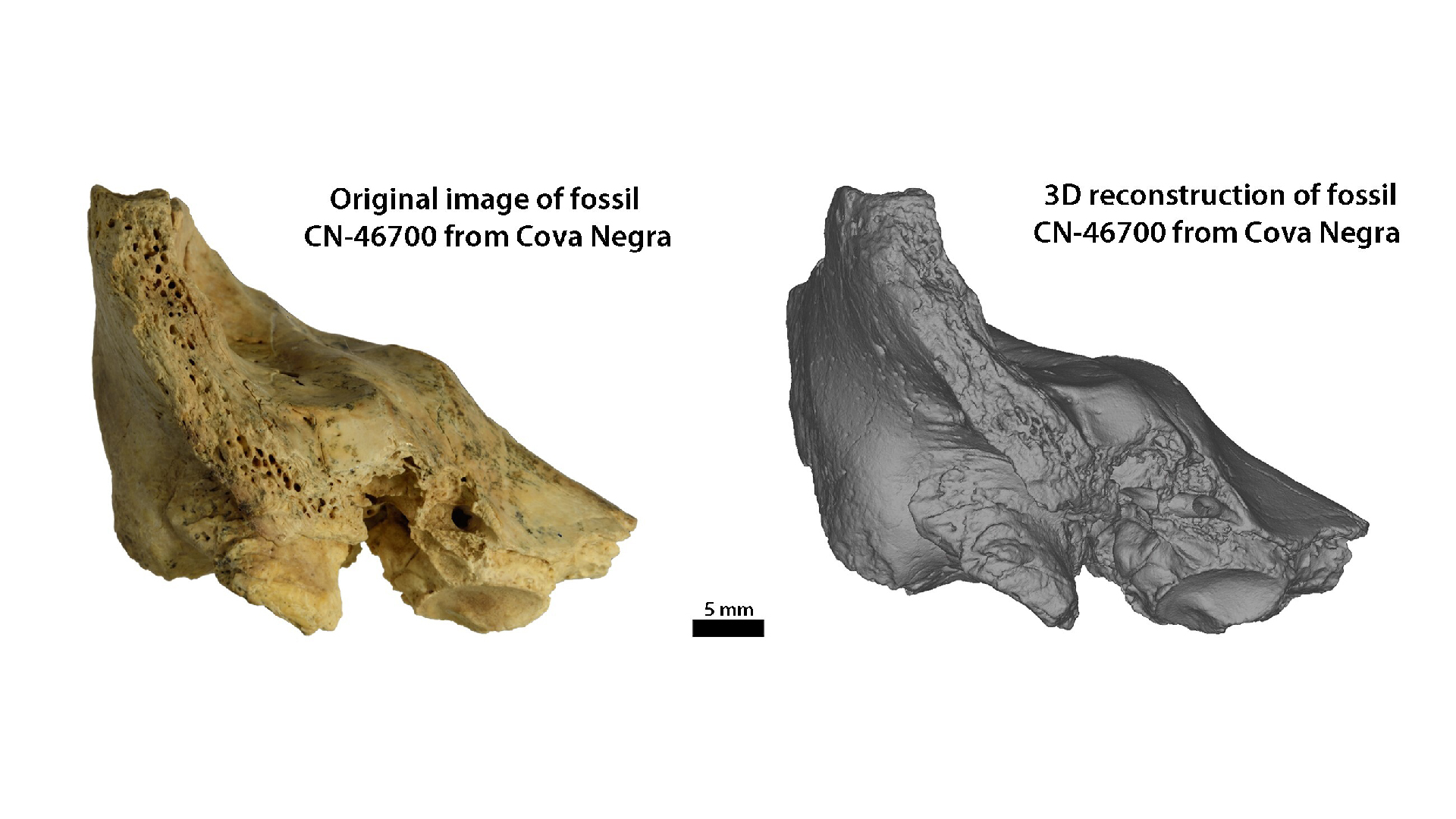

The ear bone was initially excavated in 1989 at Cova Negra (Spanish for "Black Cave") in Xàtiva, a town in the province of Valencia, in 1989. Other Neanderthal remains at the cave date to between 273,000 and 146,000 years ago. However, the bone — a fragment of a temporal bone — was mixed with animal remains and wasn't identified until recently, the researchers said.

Related: 'More Neanderthal than human': How your health may depend on DNA from our long-lost ancestors

The team used micro-CT (computed tomography) to scan the bone, which allowed them to create a digital 3D model of it.

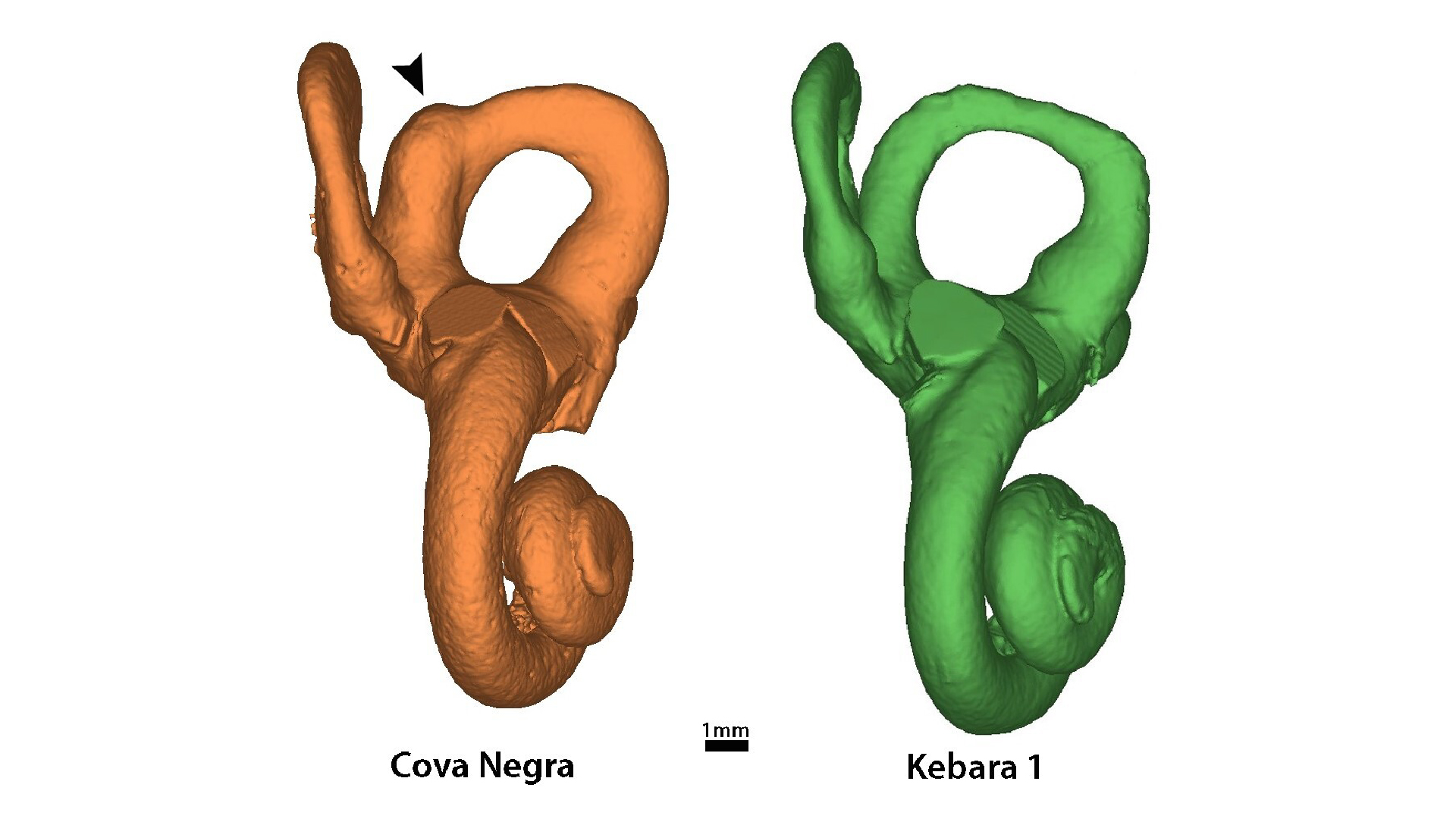

Tina's ear bone had an irregular shape that is consistent with Down syndrome, the team found. It also had other unusual aspects, including a smaller cochlea and abnormalities with the lateral semicircular canal (LSC), the shortest of the three ear canals, which, together, can cause hearing loss and severe vertigo, according to a statement.

However, because people with Down syndrome have an extra copy of chromosome 21, a genetic test would need to be done to say for sure whether Tina truly had the condition.

If she did, it's likely that Tina's condition required care from multiple individuals in her group, the team said.

It was already known that Neanderthals cared for ill members in their social groups. However, all of the known cared- for individuals have been adults, so it was unclear whether Neanderthals cared only for those who could help them in return or whether they did it out of altruism.

Given that a 6-year-old with a challenging genetic condition wouldn't have been able to help much in return, it's likely that the Neanderthals helping her were altruistic, the team said.

"What was not known until now was any case of an individual who had received help, even if they could not return the favor, which would prove the existence of true altruism among Neandertals," study lead author Mercedes Conde, professor at the University of Alcalá in Spain said in a statement. "That is precisely what the discovery of 'Tina' means."

The finding also has implications for modern humans.

"The presence of this complex social adaptation in both Neanderthals and our own species suggests a very ancient origin within the genus Homo," the researchers wrote in the study.