A new levy on shipping emissions is on the cusp of being approved at talks in London this week. If implemented, it would be the world’s first-ever global carbon tax.

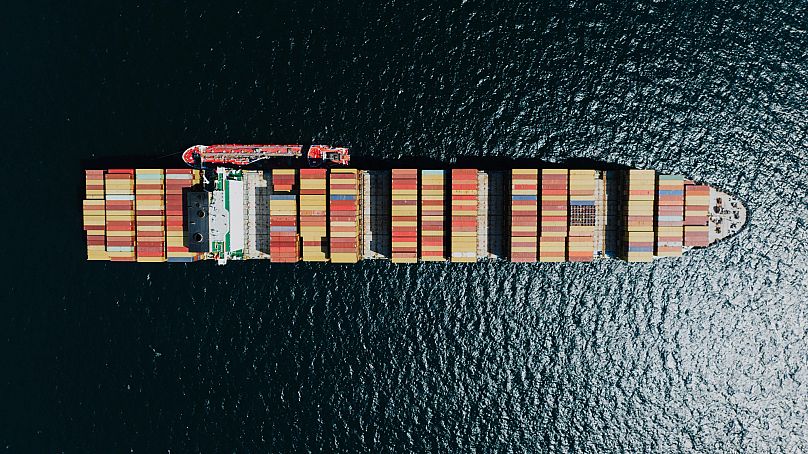

Responsible for a growing share of global CO2 emissions, shipping has been one of the hardest sectors to decarbonise.

The international nature of the industry has made it difficult to align with national climate goals, so a global carbon pricing model is widely seen as the most effective mechanism for regulation.

If adopted, a robust pricing mechanism that covers the global shipping industry would be considered one of the most important climate agreements of the decade.

What’s being proposed for the global shipping carbon tax?

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO), the regulator for international shipping, has convened a week-long meeting of its Marine Environment Protection Committee in London.

In 2023, the IMO set a target to reach net-zero emissions “by or around” 2050, in line with the Paris Agreement and targets set by other industries. The group is expected to approve regulations on maritime CO2 emissions, which were proposed in 2023.

Led by Pacific Island nations, more than 60 countries support a standard price per tonne of emissions, which they believe offers a fair path to achieving net zero.

The shipping industry is broadly supportive. The International Chamber of Shipping, which represents over 80 per cent of the world’s merchant fleet, says that a pricing mechanism for maritime emissions is “the most effective way to incentivise a rapid energy transition in shipping.”

However, countries including China, Brazil, South Africa and Saudi Arabia, are pushing for a credit trading model. Under this approach, ships that emit less than their allowance would earn credits, which could then be sold to more polluting vessels.

Critics argue that this could allow wealthier ship owners to simply buy compliance, rather than making meaningful cuts to emissions.

Ambassador Albon Ishoda, Marshall Islands’ special envoy for maritime decarbonisation, said IMO’s climate targets are “meaningless” without the levy.

Funds generated by the tax will be used to help developing countries transition to greener shipping or to fund mitigation measures in the most vulnerable countries. It will also be used to reward the production and uptake of alternative fuels.

The pricing structure has not yet been agreed upon but is expected to fall in the range of around $60 to $300 per tonne (€54 - €271).

America threatens to retaliate if a carbon tax is applied

As talks progress in London, the US has jumped in with a threat of ‘reciprocal measures’ if any carbon pricing mechanism is introduced.

A letter, circulated to many embassies of the countries in attendance at the IMO conference and seen by POLITICO, outlined the US position on a global carbon tax for shipping.

It stated that the US will not accept any international environmental agreement that adds ‘unfair’ burden to America.

“Should such a blatantly unfair measure go forward, our government will consider reciprocal measures so as to offset any fees charged to US ships and compensate the American people for any other economic harm from any adopted GHG emissions measures,” the letter stated.

The US is notably absent from the IMO meeting this week, a marked shift from the Biden administration’s previous involvement in international climate talks.

Why is a carbon tax on shipping needed?

International trade runs on shipping, with more than 80 per cent of the world’s goods carried by sea.

But the industry is incredibly carbon-intensive, contributing around 3 per cent to global CO2 emissions. Data from Statista shows that between 2012 and 2023, CO₂ emissions from international shipping increased by roughly 15 per cent to 706 Mt per year.

If the shipping industry were a country, it would be the seventh-largest emitter of CO2 in the world.

According to a report from the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA), shipping accounts for 14.2 percent of the CO2 emissions from transport in the EU, less than the road sector but approximately equal to aviation.

Unlike road and aviation emissions, limitations on shipping have been difficult to implement due to its cross-border nature and lack of clear jurisdiction.

Emissions from shipping are also projected to increase sharply in the coming decades unless significant changes are made.

What can we expect from the shipping carbon tax meeting?

With high-stakes negotiations in London this week, there is cautious optimism that a global carbon levy on shipping can be agreed upon.

However, implementation of the tax is not a foregone conclusion. Against the backdrop of sweeping US tariffs, a global trade war on the horizon and vehement reluctance from some members, achieving consensus is not going to be easy.

If the committee can agree and finalise the text for the regulations, the next step will be formal adoption. This is expected in October, and if it goes through, the rules would come into effect in 2027.