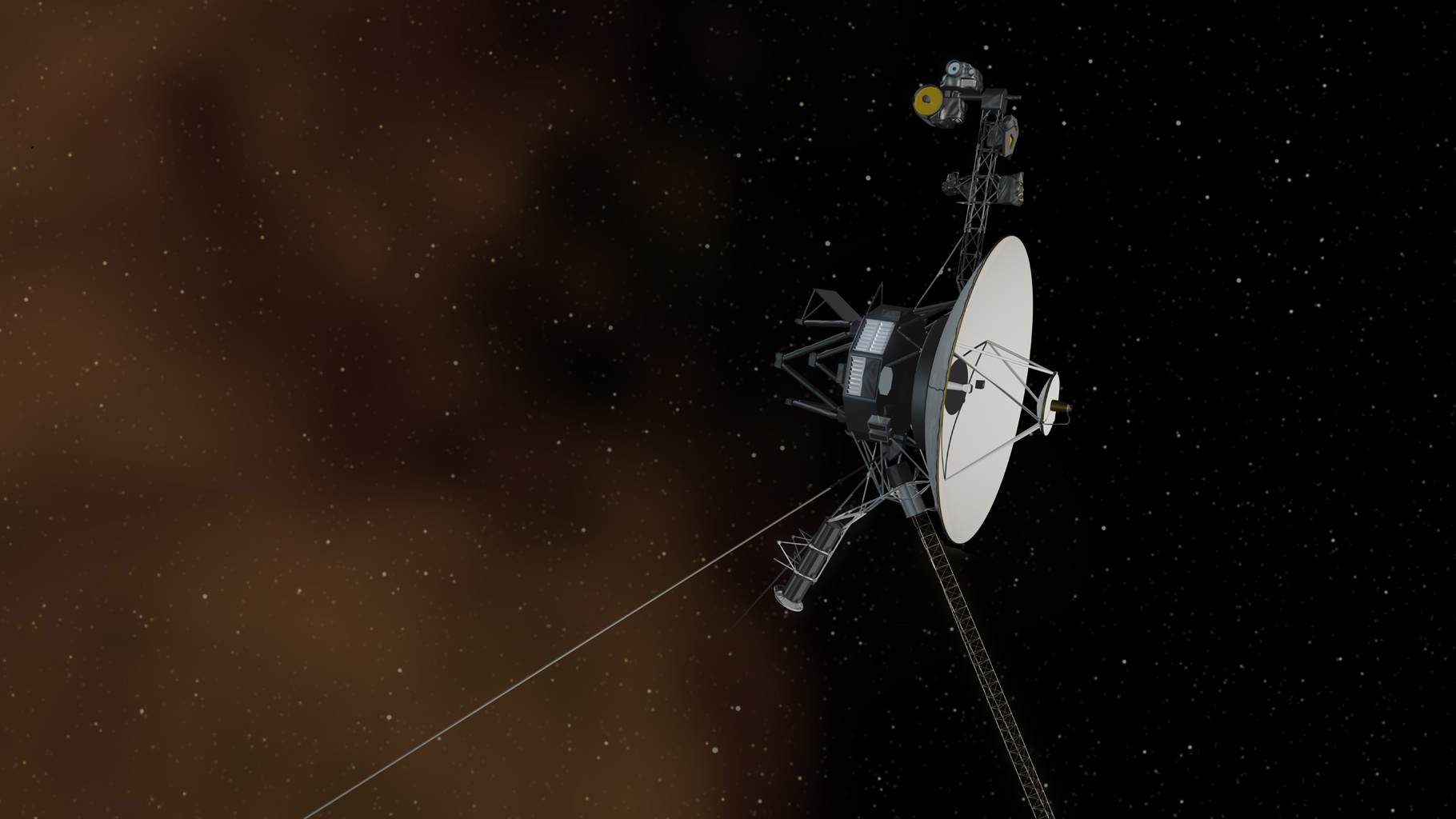

Voyager 2 can keep sending science back from interstellar space a little longer.

NASA's long-running Voyager 2 mission will postpone an instrument shutdown three years to 2026 thanks to a technical feat by engineers. The change will allow the mission, which launched in 1977, to gather valuable science in deep space.

"We are definitely interested in keeping as many science instruments operating as long as possible," Linda Spilker, Voyager's project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in southern California, said of the decision in a statement Wednesday (April 26.)

Voyager 2 and its twin, Voyager 1, will thus continue to gather valuable data deeper in space than any probes have before them. Ongoing investigations, NASA says, include examining the sun's magnetic field, the energy of the solar wind emanating from our sun and radio emissions in interstellar space.

Related: After 45 years, the 5-billion-year legacy of the Voyager 2 interstellar probe is just beginning

The Voyagers are both powered by nuclear energy, as the sun's rays are too weak for solar power so far out in deep space. The radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTG) they use decay over time, meaning the plutonium produces a little less power every year.

Engineers have already shut down heaters, alongside other non-essential systems, to prioritize science for the robust spacecraft. But power is now so low that tough decisions had to come this year for Voyager 2's five science instruments. (Voyager 1 has only four running, due to a glitch with one instrument early in its lifespan, so it has enough power for all of them until 2024.)

Solving Voyager 2's power problems came down to removing a protection normally available to stop electricity surges from damaging the spacecraft's instruments. That protection is called a voltage regulator. This regulator triggers a backup circuit that takes an extra bit of power from the RTG as surge protection in case of problems.

"Instead of reserving that power, the mission will now be using it to keep the science instruments operating," NASA officials wrote in the statement. This decision will loosen voltage regulation on the spacecraft, but both the Voyagers have experienced "relatively stable" levels of power, "minimizing the need for a safety net."

Related: Voyager turns 45: What the iconic mission taught us and what's next

Engineers will monitor the success of this strategy on Voyager 2. If everything works, Voyager 1 will use the same technique as it begins to run short on power next year, NASA officials said. Everything has been working well on Voyager 2 for a few weeks with the new procedure, they noted.

"Variable voltages pose a risk to the instruments, but we've determined that it's a small risk, and the alternative offers a big reward of being able to keep the science instruments turned on longer," Suzanne Dodd, Voyager's project manager at JPL, said in the same statement.

Both Voyagers were only expected to last four years in space and to collect solar system science at Jupiter and Saturn. A mission extension in 1981 allowed Voyager 2 to eventually fly past Uranus and Neptune, making it the only spacecraft yet to do so. Voyager 1 was high above the plane of the solar system after Saturn's flyby, but the spacecraft gathered valuable solar data from its trajectory because of the extension.

Another mission extension in 1990 aimed to bring the Voyagers to interstellar space. Voyager 1 crossed into that region in 2012, while the slower-moving Voyager 2 achieved the milestone in 2018.

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.