Mars spiders have arrived on Earth. But fear not, arachnophobes — these "spiders" aren't actual arachnids, but spider-like geological formations on the Martian surface. And NASA has just recreated them in a lab.

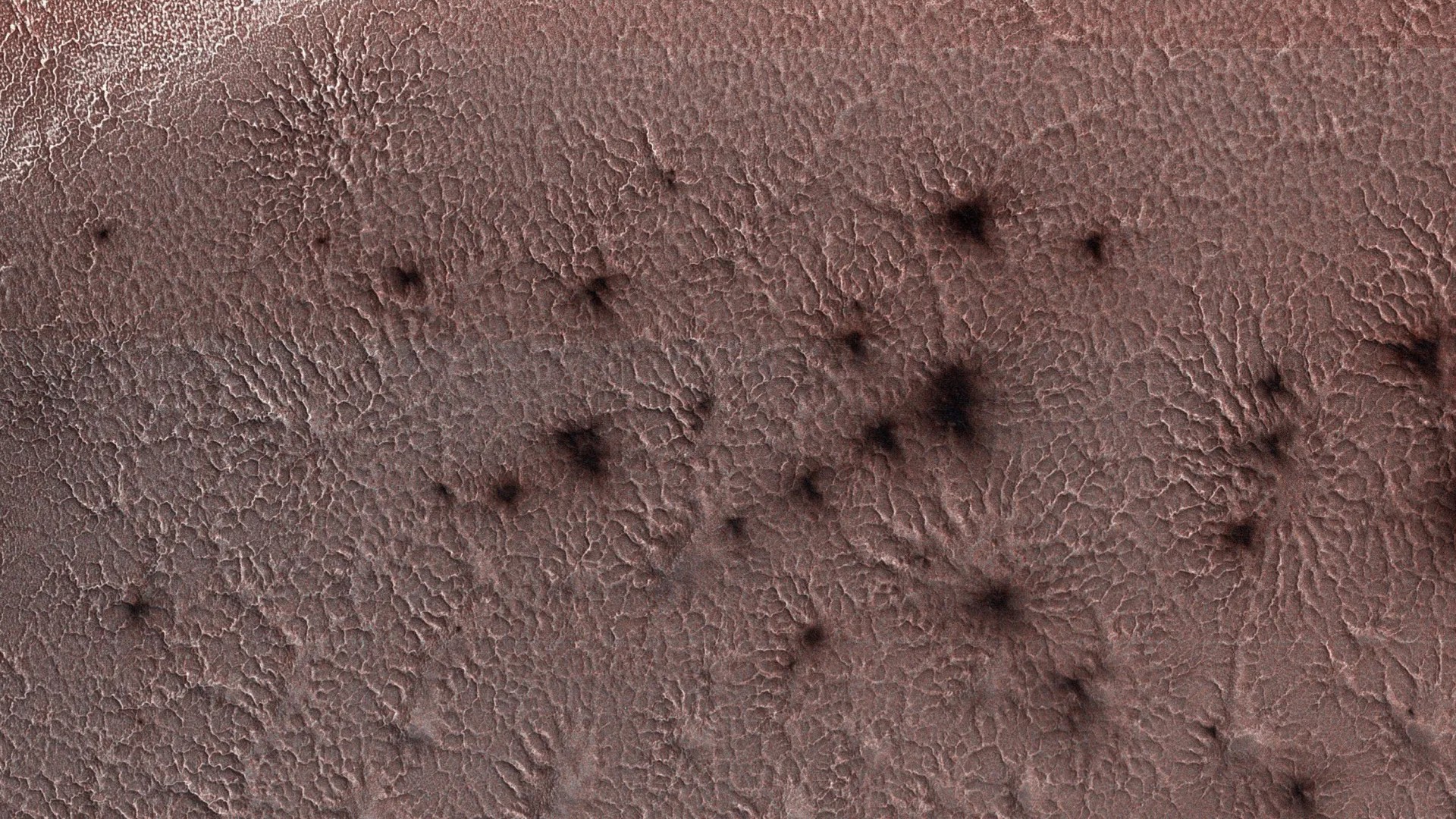

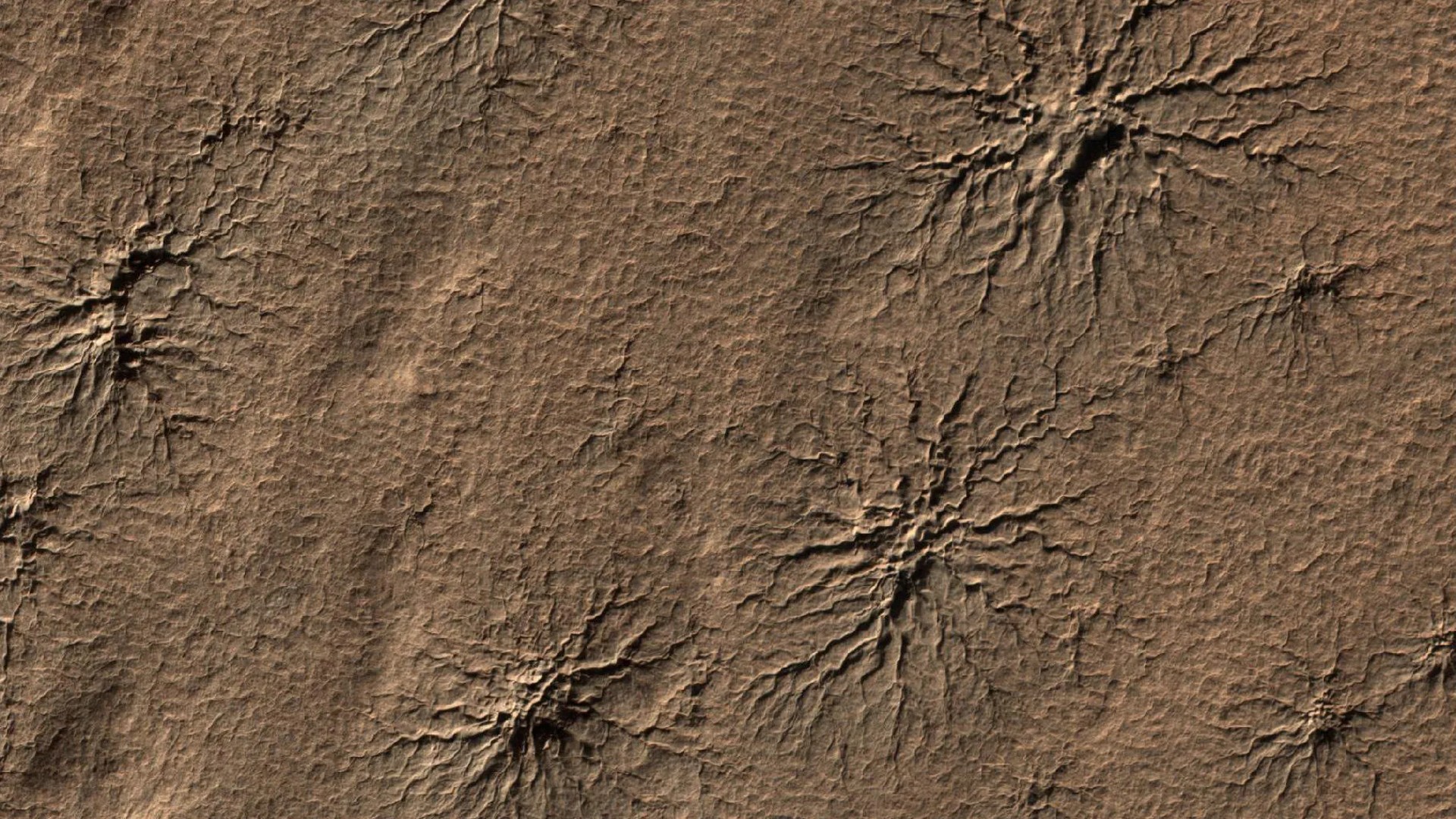

Scientists first discovered these spider-like features, or araneiform terrain, on Mars in 2003 while studying images from orbiters. They're much, much larger than spiders, though; they can stretch more than half a mile (1 kilometer) end-to-end, and they can have hundreds of "legs."

As it goes with many things on Mars, scientists had no idea how araneiform terrain formed, but a leading theory suggested it might have something to do with carbon dioxide ice. And that theory has recently been proven by researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), who have spent five years attempting to recreate araneiform terrain.

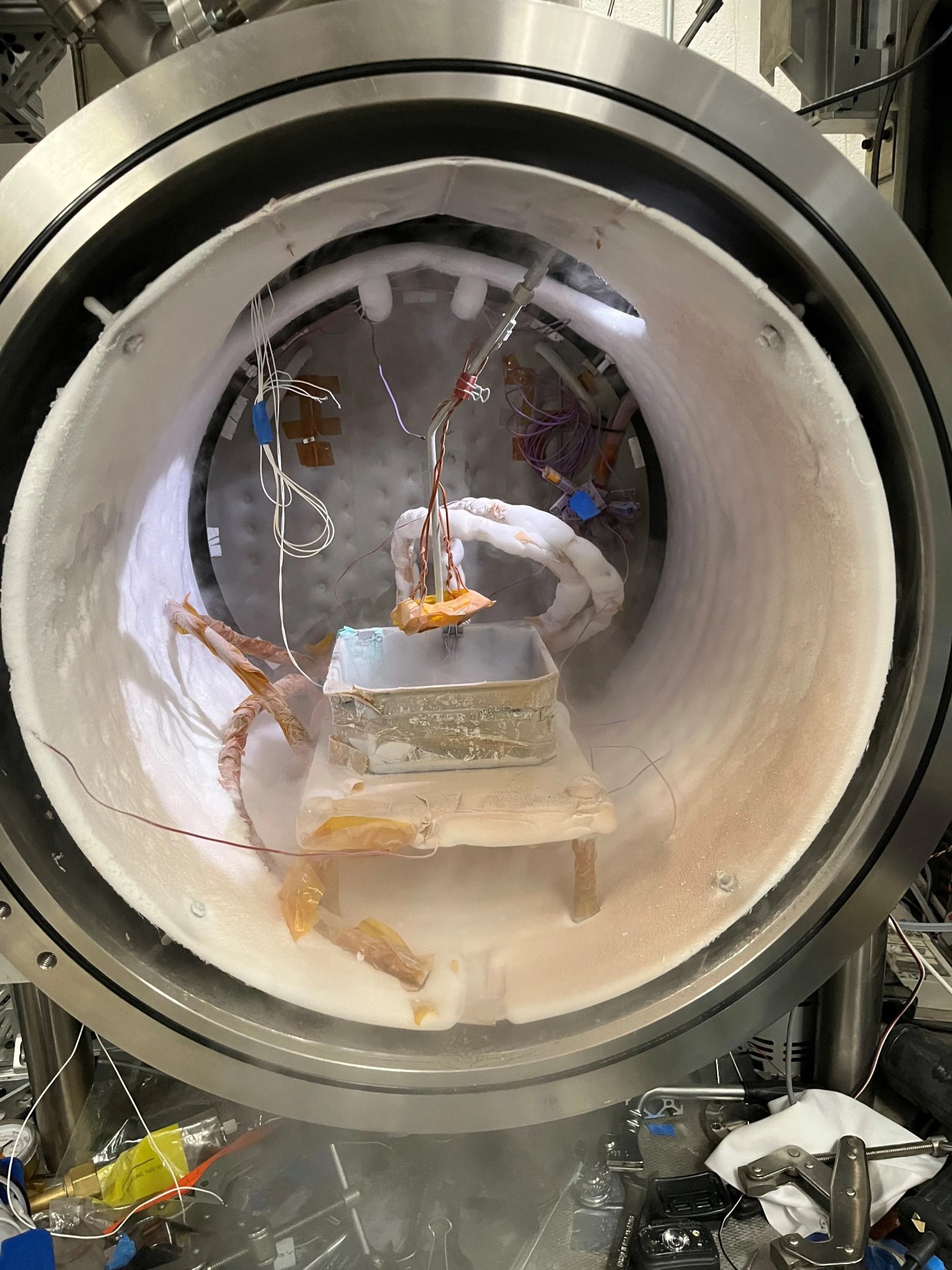

Using a liquid-nitrogen-cooled test chamber at JPL called the Dirty Under-vacuum Simulation Testbed for Icy Environments, or DUSTIE, the researchers created a simulated Mars environment.

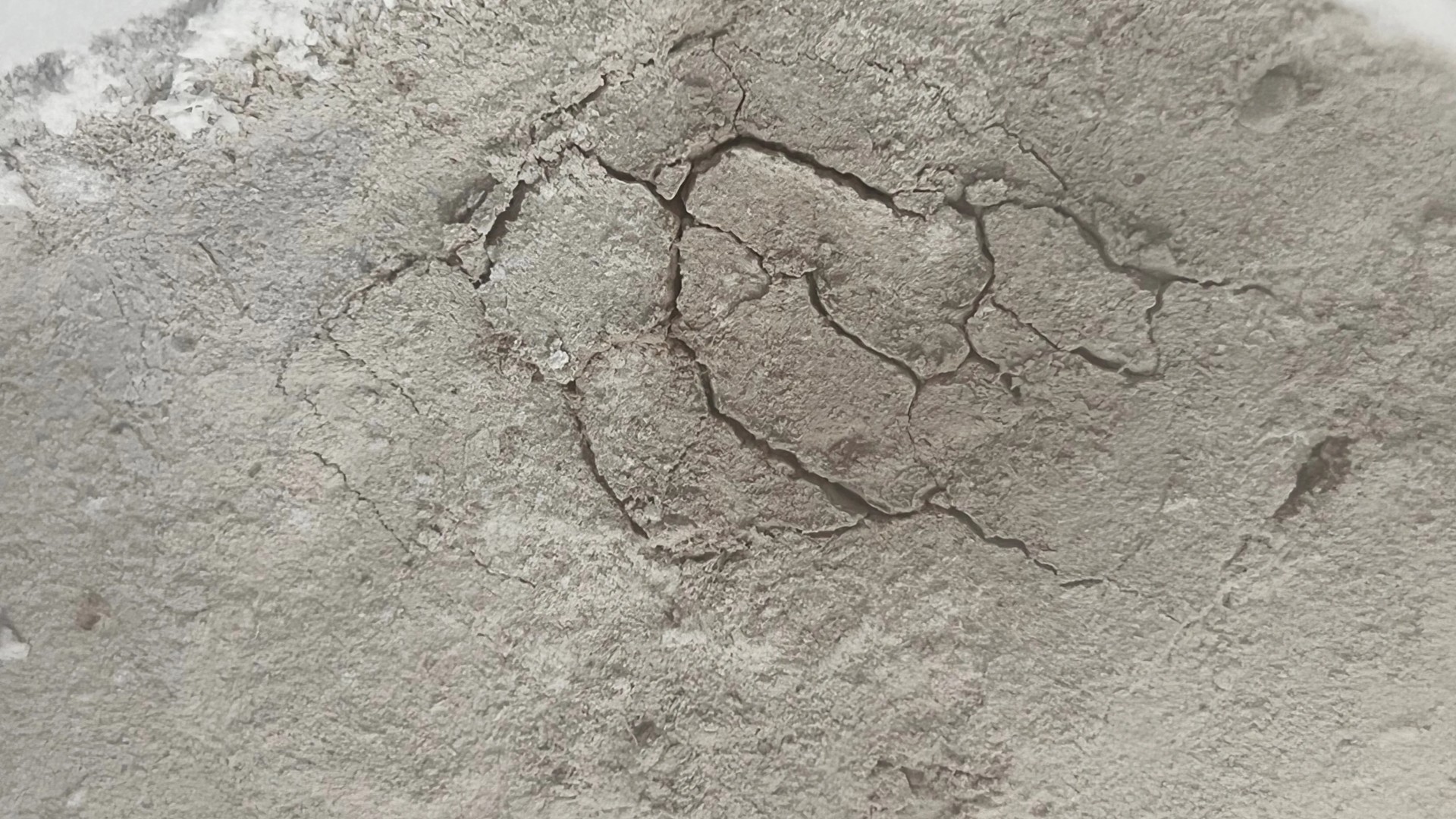

After setting DUSTIE to the correct temperature and air pressure found at the Martian poles, they cooled and condensed carbon dioxide gas into carbon dioxide ice in a Martian soil simulant. Then they heated the ice up until it cracked, releasing a plume of carbon dioxide gas and leaving behind araneiform terrain. What happened next surprised them.

"It was late on a Friday evening and the lab manager burst in after hearing me shrieking," JPL scientist Lauren McKeown, said in a statement. "She thought there had been an accident."

The process by which the carbon dioxide ice created the spider-like cracks in this experiment is called the Kieffer model. Over the cold winter, carbon dioxide ice forms in the Martian soil.

Then in spring, the sunlight heats that icy soil. The heat is absorbed by the soil, and the ice touching this soil skips the melting-into-liquid phase and simply "poofs" into carbon dioxide gas. (Per NASA, this is the same mechanism that causes dry ice to "smoke.") The gas builds up and eventually erupts out of the soil, leaving behind spider-like scars in the Martian surface.

While we now know how araneiform terrain might form, researchers will continue their experiments to answer further questions about the Martian geologic formation. For instance, araneiform terrain isn't found everywhere on Mars, so they want to investigate why it only happens in certain areas. So for now, it's back to DUSTIE they go.

A summary of the team's investigation was published in The Planetary Science Journal.