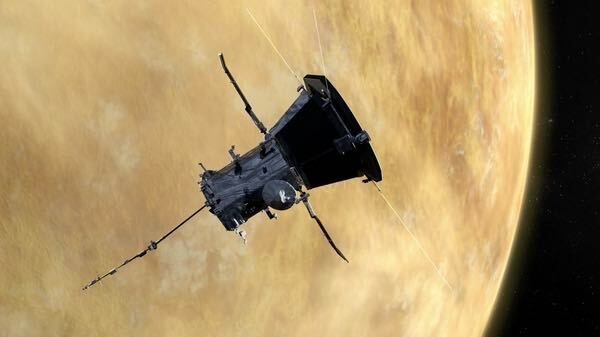

Today, NASA's Parker Solar Probe will complete its seventh swing past Venus — the spacecraft's final maneuver around the amber planet — in a flyby that will nudge the probe on a trajectory that will take it within 3.8 million miles of the sun's surface. That will be the closest that any human-built object has come to our star.

"We are basically almost landing on a star," Nour Raouafi, an astrophysicist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and project scientist for the Parker Solar Probe mission, told BBC News earlier this year. "This will be a monumental achievement for all humanity. This is equivalent to the moon landing of 1969."

The Parker Solar Probe, which is about the size of a small car, launched in 2018 on a daring mission to "touch" the sun. Scientists were hoping that it'd decode some of the hottest mysteries about our star, such as why the corona, the outermost layer of the sun’s tenuous atmosphere, gets hundreds of times hotter the farther it stretches from the sun’s surface. Indeed, the probe has already started unraveling some of these puzzles.

Gravity assists from Venus have been essential in nudging Parker closer to our star, as the spacecraft relies on the planet's gravitational tides to reduce its orbital energy and tighten its choreographed orbit around the sun.

"Venus 7 is the critical gravity assist for Parker Solar Probe to eventually achieve its minimum solar distance," Yanping Guo, who is the mission design and navigation manager Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Maryland, said in a recent NASA statement.

While the probe is tailored to study the sun, these repeated swings past "Earth's evil twin" — which scientists say has not had enough robotic visitors in the past decades — have prompted Parker's operators to turn on its instruments and collect precious bonus science. During Parker's third Venus flyby in July 2020, for instance, scientists were surprised to find the spacecraft's camera could peer through Venus' dense clouds all the way to its surface, revealing distinct features, such as continental regions, plains and plateaus, carved onto the world.

The camera, called the Wide-Field Imager for Parker Solar Probe, or WISPR, also recorded the faint flow caused by heat emanating from Venus' nightside, which, at 860 degrees Fahrenheit (460 Celsius), would be "like a piece of iron pulled from a forge," Brian Wood of the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C. said in a NASA statement. Parts of the WISPR images also appeared brighter than expected, suggesting the camera might have picked up information about the Venusian surface not seen by previous spacecraft, such as subtle chemical differences on the surface or variations in age, possibly caused by recent lava flows.

To study the surface features in further detail, mission scientists will once again point WISPR toward Venus on Wednesday as the Parker Solar Probe swoops within 233 miles (376 km) of the planet's surface.

"Because it flies over a number of similar and different landforms than the previous Venus flybys, the Nov. 6 flyby will give us more context to evaluate whether WISPR can help us distinguish physical or even chemical properties of Venus' surface," Noam Izenberg, a planetary geologist at APL, said in a recent NASA statement.

On Christmas Eve, the Parker Solar Probe will graze the sun's "surface" — the photosphere, or sun's visible part — at a record 430,000 miles per hour (692,010 kilometers per hour). Mission control will be out of contact with the spacecraft during that time, but will be looking for a beacon tone on Dec. 27 that will confirm the success of closest approach and the spacecraft's health.