NASA's Juno spacecraft has detected salts and organic compounds on the surface of Ganymede, Jupiter's largest moon.

The detection was made during a June 2021 flyby in which Juno analyzed Ganymede using its Jovian InfraRed Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) spectrometer, an instrument designed to study the chemistry and interactions within Jupiter's atmosphere and those of its moons. Ganymede, one of those moons and the largest moon in the solar system — at 3,270 miles (5,268 kilometers) wide, it's bigger than the planet Mercury — has a vast ocean underneath its icy crust.

During its 2021 flyby of Ganymede, Juno's JIRAM instrument detected salts such as hydrated sodium chloride, ammonium chloride, sodium bicarbonate, and possibly even organic compounds known as aliphatic aldehydes. The discovery of these compounds and salts can help astronomers better understand how Ganymede formed and evolved and possibly shine light on the chemical composition of its subsurface ocean.

Related: Jupiter has a creepy 'face' in haunting Halloween photo by NASA's Juno probe

Nearby Jupiter has such a strong magnetic field that organic compounds and salts on the surface of Jovian moons would have a hard time surviving. However, the region around Ganymede's equator appears to be sufficiently shielded from the electrons and heavy ions that emanate from Jupiter's magnetic field to sustain these compounds.

"We found the greatest abundance of salts and organics in the dark and bright terrains at latitudes protected by the magnetic field," said Scott Bolton, Juno's principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. "This suggests we are seeing the remnants of a deep ocean brine that reached the surface of this frozen world."

The presence of these salts and organic compounds could indicate the presence of hydrothermal activity deep under Ganymede's icy surface, or interactions between its subsurface ocean and rocks deep within the planet.

"Extensive water–rock interaction could achieve such a balance and would also be consistent with the presence of sodium salts as an independent indicator of aqueous alteration inside Ganymede," the authors wrote in a paper published in the journal Nature Astronomy on Oct. 30.

However, there could be other processes that created these salts aside from the activity of a salty inner ocean, the authors add. "Because Ganymede has a substantially thicker crust than Europa, exchanges between its deeper interior and surface may not be responsible for its surface composition, and thus may reflect exchange between the shallow crust and surface, or exogenous deposition," they wrote in their study.

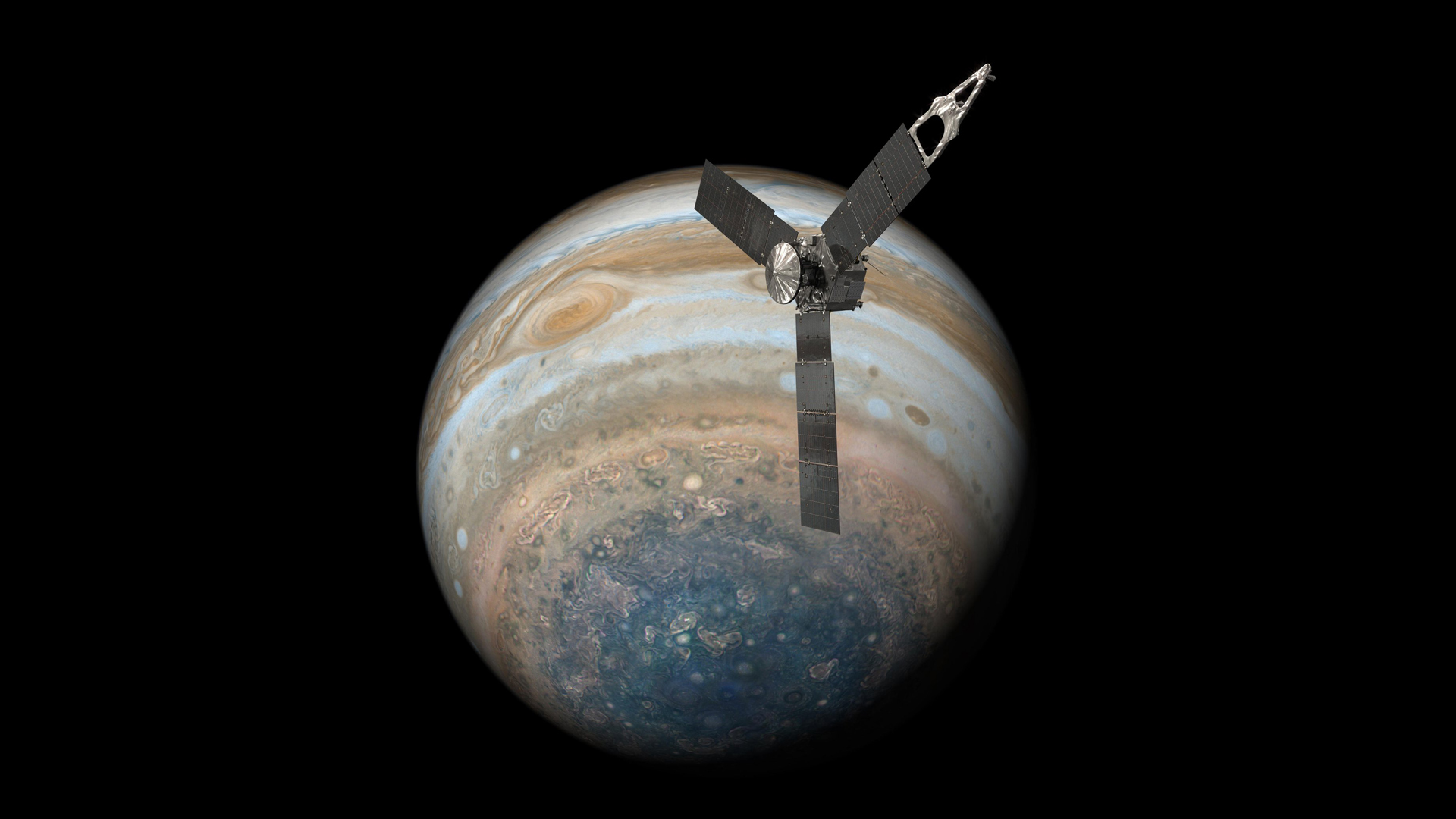

Juno launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida on Aug. 5, 2011 and is only the second mission to orbit Jupiter, after NASA's Galileo probe. Juno was designed to study the gas giant's weather, magnetic environment and history. The probe's mission has already been extended twice, and it's currently scheduled to operate through September 2025.

A study of Juno's observations of salts and organics on Ganymede's surface is published in Nature Astronomy.