Astronomers have discovered a Jupiter-size planet that "shouldn't exist" after the sudden and violent expansion of its host star.

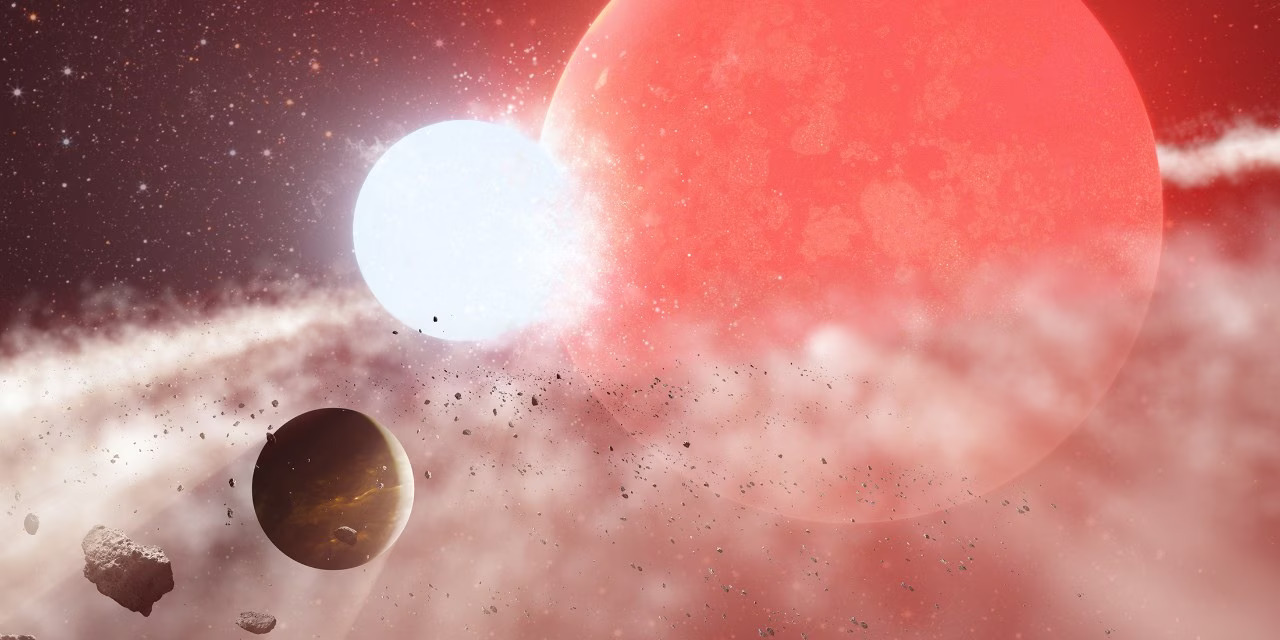

The gas giant 8 Ursae Minoris b — also known as Halla — is a "hot Jupiter" planet located 520 light-years from Earth. The enormous world seemingly faced certain destruction after its host star, Baekdu, ballooned to thousands of times its original size to devour any planets in its orbit.

And yet, mysteriously and miraculously, Halla survived. Astronomers published their findings June 28 in the journal Nature.

Related: A 'captured' alien planet may be hiding at the edge of our solar system — and it's not 'Planet X'

"Engulfment by a star normally has catastrophic consequences for close orbiting planets," study co-author Daniel Huber, an astronomer and research fellow at the Sydney Institute for Astronomy in Australia, said in a statement. "When we realized that Halla had managed to survive in the immediate vicinity of its giant star, it was a complete surprise."

As Baekdu exhausted its supply of hydrogen fuel, the star would have expanded immensely, inflating up to 1.5 times Halla's orbital distance, the researchers added. Halla should have been completely engulfed — and incinerated — before the dying Baekdu shrank back to its current size. However, that doesn't seem to have happened.

Halla was first discovered by Korean astronomers in 2015, using a technique known as the radial velocity method, which searches for the tugs of hidden planets in the wobbling of distant stars. Yet Halla presented a mystery: It was orbiting the star Baekdu (which has a radius that's nearly 11 times that of the sun and a mass 1.6 times our star's), which had already transformed into a red giant.

For most of their lives, stars burn by fusing hydrogen atoms into helium. Once they have exhausted their hydrogen fuel, however, they begin fusing helium, leading to a massive increase in energy output that causes them to swell to hundreds, or even thousands, of times their original size. As the stars expand, they gobble up their inner planets, transforming into huge stars called red giants.

To establish that Halla was one of Baekdu's original planets and not a cosmic interloper, the researchers made observations using the Keck Observatory and the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope in 2021 and 2022, which confirmed that the planet's 93-day, near-circular orbit had been stable for more than a decade.

Still, the astronomers think it's almost impossible that Halla was ever touched by its star, which lies about half the distance from the planet as Earth does from the sun.

"We just don't think Halla could have survived being absorbed by an expanding red giant star," Huber said.

Instead, the researchers have narrowed the possibilities to two options: Either Halla was born after Baekdu transformed into a red giant, or Baekdu was once one of two stars in a binary system that later merged, preventing either from expanding sufficiently to consume Halla.

"The system was more likely similar to the famous fictional planet Tatooine from Star Wars, which orbits two suns," study co-author Tim Bedding, an astronomy professor at the University of Sydney, said in the statement. "If the Baekdu system originally consisted of two stars, their merger could have prevented any one of them from expanding sufficiently to engulf the planet."