On the third night of sailing the East Indian Ocean, the crew of the yacht Ganesha watched the Sun go down and the sky darken — and then things got weird.

“We realized that the sea was luminous,” recalls crewmember Naomi McKinnon of the August 2019 trip.

“We were like, ‘What the hell, why does the sea look so awesome?’”

McKinnon and two crew-mates hustled into the galley to wake the captain and the rest of the crew. Sailors have been describing these encounters for centuries. What they saw brought to mind the stories of Moby Dick and Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea — both feature strange salt-dog tales of glowing seas, like this moment in the latter novel, published in 1869-1870:

“About seven o’clock in the evening, the Nautilus, half-immersed, was sailing in a sea of milk. At first sight the ocean seemed lactified.”

Flash forward to August 2019, and the Ganesha’s ship logbook for that night reads:

When waking up at 2200 the sea was white. There is no moon, the sea is apparently full of ? plankton ? but the bow wave is black! It gives the impression of sailing on snow!

None of the Ganesha’s crew knew what, exactly, they bore witness to that night. They managed to take a few photos to document the sight, despite the obscuring qualities of the low light conditions.

Now, almost three years later, scientists have finally confirmed that what the crew saw was no visual illusion — in fact, it was bacteria.

What’s new — The crew’s photos are the first-ever confirmed images of a breathtaking phenomenon known as “milky seas”, where trillions upon trillions of bioluminescent bacteria light up the ocean with their glow.

These elusive events happen only once or twice a year, usually in the Indian Ocean. Even scientists who have spent decades studying the phenomenon have never been lucky enough to witness it in person. One of these experts is Steven Miller, an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University. Miller published a new study based in part on the crew of the Ganesha’s experience and satellite observations on Monday, July 11 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

How the discovery was made — Miller has been scouring satellite data for evidence of milky seas for years. In 2021, while examining observations from the same year as the Ganesha sailed the Indian Ocean, Miller identified an anvil-shaped patch of light off the southern coast of Java, Indonesia, spanning over 100,000 square kilometers — about the size of the state of New York.

Without on-the-ground reports, Miller couldn’t be sure that this was a milky sea event. Yet after ruling out other plausible explanations, he published his hypothesis in a July 2021 Scientific Reports paper, hoping that someone, somewhere, might read his paper and confirm his hunch — his data showed there had been sailors out there at the same time the satellite observations were collected.

“The satellite imagery, it sees low light signals,” Miller says. “We were seeing lights from boats, they look like little points of light in the water.”

His wish came true: In late 2021, McKinnon got in touch. After interviewing the crew and comparing the ship’s course to the coordinates of the satellite imagery, Miller confirmed that the anvil-shaped splotch he had spied in the observations from 2019 was indeed the same milky sea the crew of the Ganesha saw in August that year.

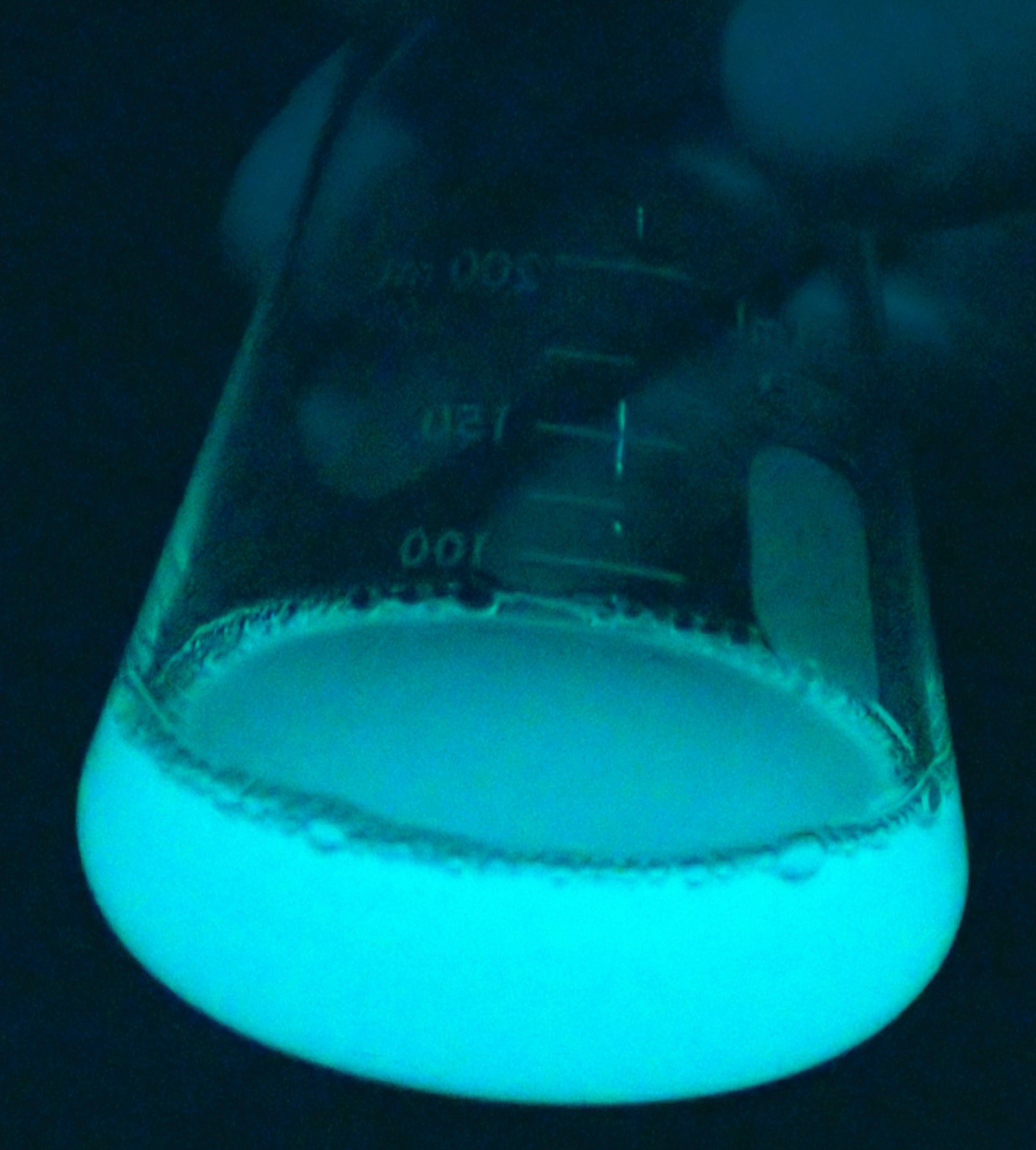

Diving into the details — The crew of the Ganesha also gave scientists a few clues about what may causing this rare effect. The culprit may be Vibrio harveyi, bacteria that colonize and eat algae. When enough of these bacteria are present — here, 100 million bacteria in one milliliter of water — they begin to omit a soft glow.

The crew also gives insight into the behavior of the bacteria. When they went to check the ship’s toilet, which draws water from the ocean, sure enough, it was glowing, “like something radioactive from a cartoon,” McKinnon says.

To get a closer look, they then hoisted a bucket of seawater up to the deck. Little pinpricks of light floated in the water but disappeared when they stirred the water — similar to how the water at the front of the ship darkened when disturbed by the bow as it plowed through the waves.

The darkening effect was not something the scientists had predicted, says Edith Widder, a marine biologist and founder of the Ocean Research and Conservation Association who was not involved in the new study. Usually, light-emitting sea creatures are triggered by physical movements in their environment. But in this case, the opposite appears true, she says. Also, bioluminescence usually manifests in brief flashes, not as a sustained glow.

One hypothesis is that V. harveyi’s light may lure in fish to eat the bacteria, which are right at home in the fish’s digestive tract, explains Kenneth Nealson, a microbiologist at the University of Southern California. He was not involved in the recent research.

What’s next — Scientists have reproduced V. harveyi’s glow in the lab, but how these bacteria come to illuminate whole swathes of the ocean remains a mystery.

Milky seas likely emerge from the complex interactions of different species and their oceanic and atmospheric environments, says Youri Timsit, who studies environmental microbiology at the Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography. Timsit was not involved in the recent research.

Now that scientists can find milky seas through satellite imagery, they can collect data to study what gives rise to these events. Miller hopes they might predict where and when it will happen next and then he can go study it in person.

For now, we can live vicariously through others like McKinnon.

“I never thought at the time that I was witnessing something so rare,” McKinnon says. “We sat up for a long time during the night basking in the glow, accompanied by a light tropical breeze. It was definitely an experience I never want to forget.”