On a large asteroid named Vesta, mysteriously curved gullies and fan-shaped deposits may have formed from short-lived flows of saltwater, a new study reports — a discovery that's quite surprising because Vesta shouldn't really have any water at all.

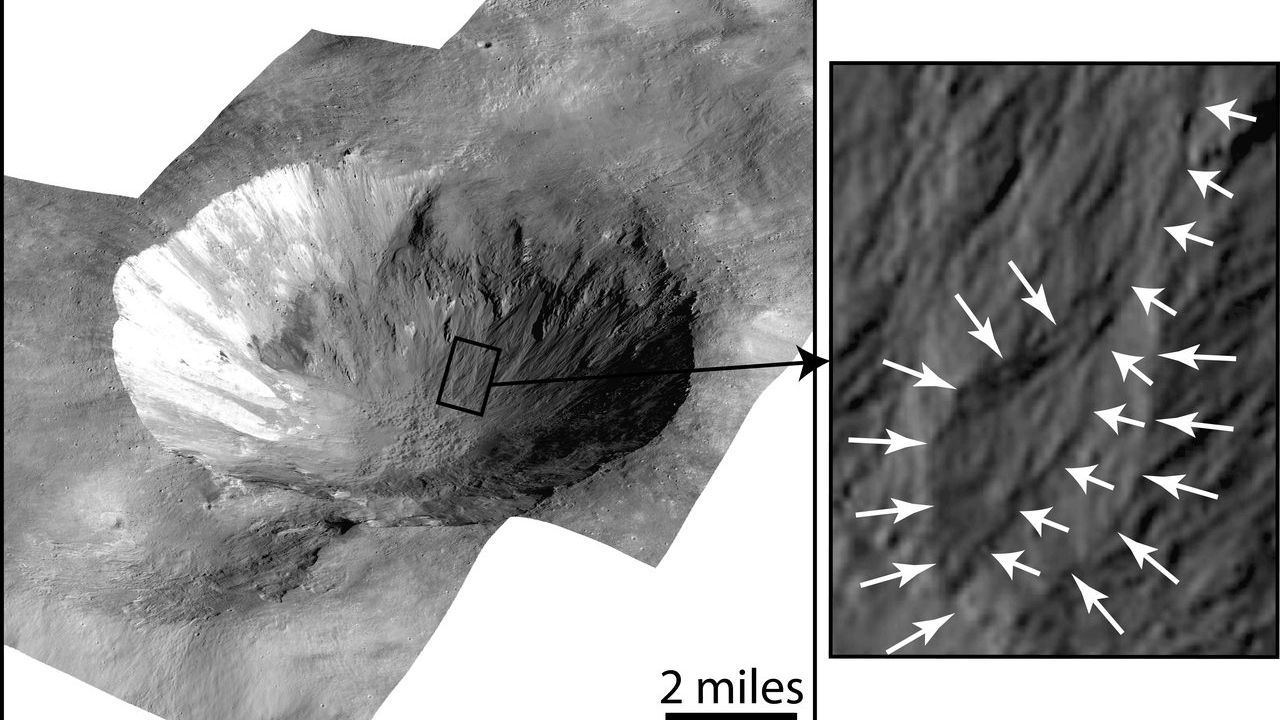

Vesta, the second biggest member of the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, has existed for 4.5 billion years with an utter lack of atmosphere — so, any water the asteroid harbored on its surface should have long escaped into space. Yet, close-up images of the asteroid, captured by NASA's Dawn spacecraft over a decade ago, showed narrow gullies and canyons carved into impact craters on the object. Puzzlingly enough, that led scientists to conclude that liquid water probably flowed on its surface relatively recently.

A recent experiment led by Michael Poston, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Texas, suggests asteroid strikes excavated and melted ice hidden below Vesta's surface. The resurfaced ice could have then flowed as liquid brines along the walls of newly formed craters — long enough to sculpt curved gullies and fans of debris, the researchers say.

Inside a test chamber at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, the researchers simulated the pressure ice experiences on Vesta to record how long liquid would take to refreeze after melting from an impact. Pure water froze too quickly in a vacuum, the experiment revealed, but salty water flowed for at least one hour.

Related: Good news for life: Mars rivers flowed for long stretches long ago

The features seen on Vesta are likely many meters thick, however, meaning they probably resulted from briny water flowing for longer than an hour. Still, Poston said in a statement that flows of just tens of minutes are "sufficient for the brine to destabilize slopes on crater walls on rocky bodies, cause erosion and landslides, and potentially form other unique geological features found on icy moons."

If the findings hold true for other dry and airless bodies, water may have graced them as well in the recent past, and is possibly even being expelled in the present, he added: "There may still be water out there to be found."

Some of it may soon be cataloged by NASA's Lucy probe, which is scheduled to arrive at a set of eight Trojan asteroids near Jupiter in 2027.

This research is described in a paper published Oct. 21 in The Planetary Science Journal.